|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Anything Goes: Live Art in Falmouth Wellington Terrace, Falmouth 6-7 June 2008 Theron Schmidt

One of the great things about the category of ‘live art’ is that it isn’t really a category. Rather than being defined by use of materials or specificity of context, it is instead an attitude, a permissiveness, a deliberate and productive confusion. This abundant confusion was very much evident at Live Art Falmouth 2008, the second year of this platform for emerging as well as established artists. This year’s organisers, artist-curators Paul Carter and Alexandra Zierle, described their primary intention to be the lowering of boundaries and the breaking down of art-world hierarchies, so that each work could be engaged on its own terms. For this reason, festival visitors are not pushed in any particular direction: there are no posters highlighting the ‘big name’ artists, no indication of ‘prime time’ performance slots, just an overwhelming printed table of all 75-odd presentations being made over the two days, with just two short lines as a clue to what each piece might be. It’s up to the visitor to find her or his own path. This was mine.

Performance and everyday life

The lives of those outside the festival are unwittingly drawn into the festival in Holly Bodmer’s ‘I Come in Peace’. Over four and a half hours, Bodmer participates in a variety of online forums like Visual Chat and Second Life; a projection of her computer screen is cast onto the venue wall, along with the image from a camera trained at her face (even though she herself is in the room). Exchanges within the elaborate, avatar-based forums (like IMVU Chat or Second Life) tend to get bogged down in the complex range of options offered by the technology, but the simple text-based chats are a breathless and horrifying distillation of human interaction. Within Visual Chat, Bodmer accepts any invitation she receives, meaning that she often has upwards of a dozen simultaneous chats, flipping between screens as quickly as she can. Even at 11 A.M., most of the chats lead to the same thing, though some waste no time in getting there: ‘Hi you horny?’ is the opening line of one conversation. At first this feels uncomfortably voyeuristic, as strangers unknowingly expose themselves to spectators who find it hilarious – some participants even agree to spend their credits for a video chat, only to find that all Bodmer will show them are blurry glimpses of a small wooden doll. But I realise that Bodmer is not necessarily any more manipulative or predatory than those with whom she is chatting, who are just as keen to see her expose herself on their screens as she is asking them to do on ours.

Framing interaction within an experience presented as ‘art’ inevitably

changes the experience, and some of the work at the festival

interrogates the nature of that self-reflexive transformation. In

‘audience: a collection of silences’, Rachel Gomme sets out to

record a series of shared silences, each contributor individually

spending ten recorded minutes in a room with her with no compulsion to

(or prohibition against) making any sound. The far from emptiness of

silence is the obvious subject of her work, but so too are the dynamics

of the entire interaction, which includes a contract, signed in

duplicate by both parties, in which the contributor can choose to give

over all rights to the recording in observance of ‘the Copyright,

Designs,

In

‘Key Notes’, Richard Layzell also strips back a common

interaction to its essentials, removing any

Do animals understand art?If one

strand of work in the festival took its focus to be human interaction,

then another wholeheartedly embraced the non-human. This was sometimes

comical, as with Kayleigh O’Keefe’s melancholy attempt to become

a shark or Bill Leslie’s riotous vision of an ape trying to make

it in the world of art school, struggling

One of the most revelatory pieces of the festival was Michael Fortune’s film piece ‘Reigning Cats and Dogs’ (despite its rather uninspired title), which looks through different eyes at what feels like a completely different world. Using long, fixed frame camera shots, with the camera usually placed at floor level, we see various vignettes in a manic household which a large family shares with an uncountable number of cats and dogs. A room full of cats waits tensely outside a closed door, their changes in attention signalled by countless twitches of ears and movements of heads. Three dogs jump over and over again, inexhaustibly, at a door handle, until finally a visitor is let in. Four cats eat, all attention on the task at hand, while a dog watches them from the doorway, barking. A dog runs maniacally through a landscape of twinkling Christmas lights, finally knocking over the camera itself. It’s the ambient human life in each shot – people moving about, watching TV, going to the loo – that makes it extraordinary. In the midst of an art festival’s obsessive examination of the human condition (and what could be more symptomatic of humanness than art itself?), Fortune’s film is a refreshing look from the outside.

The autonomy of ritual

Bennett’s text piece suggests art as an autonomous zone, one in which

its rituals follow their own rules and which creates its own alternative

reality. This claim to autonomy underlies several other works in the

festival, which derive significance from their self-asserted status of

ritual. In ‘Burning and Breaking’ (picture below left),

Nathan Walker wraps his dress shoes in paraffin-soaked

cloth. While the shoes burn, Walker repeatedly breaks bricks against

each other, his labour growing more desperate and violent as his muscles

tire. Finally, he scrapes shards of broken brick across his bare chest

– the final gesture in an angry disavowal in which the

The tension of referentiality comes across strongly in Rachel Parry’s ‘Baba Yaga’s Bastard Child’. Wildly costumed in shells, rags, and dreadlocks, with logs for shoes and designs painted on her skin, Parry leads volunteers from amongst the audience through a series of eerie ceremonies. Some have the lines on their palm traced in red liquid; some are sprinkled with salt or enrolled in incantations; others are encouraged to pass food and drink through the remainder of the audience. It’s not clear whether there is an intended actual effect of these proceedings – is this a representation of magic, or is it intended to be actually magical? In the theatre, we are accustomed to taking the two as interchangeable; at the same time as Live Art Falmouth, a psychic medium is playing at the town’s Princess Pavilion. And of course, some things can’t be represented without actually doing them, as in the projected video which shows pins being stuck in the crease of the hand which runs from the index finger to the base of the palm. Perhaps these theatrical spaces are the spaces we have left for the occult, the ritual, the flaunting and re-writing of reality. But when the lights come back on after Parry’s performance and we look around blinking at each other, it’s not clear what we’ve experienced.

The power of images

Also

effective were works in which the spectators were incorporated within

the composition. In ‘Two basic assumptions of this theory’ (picture

right), Jessica Morris piles cinder blocks to build a wall

immediately in front of her audience. On the back wall, a projected

image shows shadow figures labouring maniacally, superimposed over each

other. Gradually it becomes apparent that a live image of the audience

is being projected

Interventions in public spaceNot

all of the work at the festival takes place within the confines of the

hosting university building, and a few works seek to intervene in the

daily rhythms of Falmouth. ‘The Park Bench Reader: My Favourite Novel’

(picture below), by Bram Thomas Arnold, places a dozen or

so participants at the end of the Prince of Wales Pier,

More subtle and pervasive is the ‘Sounds of the Serengeti’, by Tim Crowley, which plays African birdcalls, monkey screeches, and occasional grunting over the noise of Falmouth’s main shopping street. The sound is spread across multiple speakers, so it creeps up on the listener’s consciousness (if it is even noticed at all), and the source of the sound is hidden by the narrow street and high shop fronts. There’s an imperceptible mix between the ‘alien’ and the ‘native’ sounds of the gulls and cars, and it becomes particularly hard to distinguish the animal from the human when I walk the street late on Saturday night, the air filled with mating calls and displays of aggression.

Looking to the futureThese works in public spaces raise the question of how this festival will situate itself as it develops in future years: will it focus on providing a protective environment which promotes research and risk-taking by artists, or will it aim to have a profile and impact within Falmouth itself? As Dartington College of Art’s merger with University College, Falmouth, nears its 2010 completion, what changes will evolve in the relationship between academic study, institutional reputation, and artistic practice? These questions will hopefully be answered organically, as the festival continues to develop from year to year. The affiliation of such an ambitious, wide-ranging performance festival with an academic institution is an opportunity and strength for both parties, and I hope that institutional support will continue to let the festival discover its own identity as a platform for live art in the South West.

Theron Schmidt is a writer and performer based in London. He was selected for Writing from Live Art, a Live Art UK initiative, and his critical writing has been published in AN Magazine, Dance Theatre Journal (forthcoming), Platform, and Real Time (Australia). Photos by Georg Dietzler, Laura Frisa, Lucy Cran, Nathan Walker, Oliver Irvine & Joseph Thomas |

|

|

with

the padded fingers and obstructed visibility of his costume to open

paint cans, position lights, hang and paint a canvas, and document

himself with a video camera (both pictures above right). With her

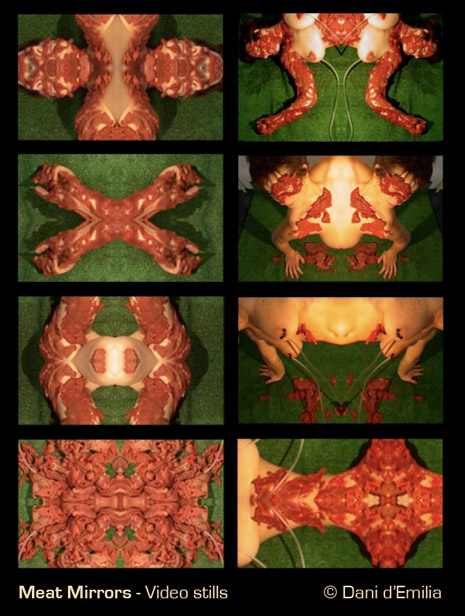

series ‘Steps Toward Becoming Animal’, Dani d’Emilia (picture

left) takes a more serious, visceral approach. In the video piece

‘Meat My Mirrors’, parts of the artist’s body combined with ground meat

and tubes of milk are rendered unrecognisable by mirror images doubling

and quadrupling. The resulting images undulate with a strangely

beautiful yearning, perhaps the desire to offer sustenance within an

endless cycle of regurgitation.

with

the padded fingers and obstructed visibility of his costume to open

paint cans, position lights, hang and paint a canvas, and document

himself with a video camera (both pictures above right). With her

series ‘Steps Toward Becoming Animal’, Dani d’Emilia (picture

left) takes a more serious, visceral approach. In the video piece

‘Meat My Mirrors’, parts of the artist’s body combined with ground meat

and tubes of milk are rendered unrecognisable by mirror images doubling

and quadrupling. The resulting images undulate with a strangely

beautiful yearning, perhaps the desire to offer sustenance within an

endless cycle of regurgitation. By

removing the human dimension from the work, another, almost autonomous,

logic starts to emerge. This is the case with Stephen Cornford

and Matthew Appleby’s ‘Human Separation’ (picture right),

in which the artists create an ensemble of patchwork machines, one

driving a bow across a modified ‘cello, another beating percussively at

the frets of an electric guitar. Once each machine has been put in its

place and the instrument plugged in, the two humans step away, leaving

the noise to build across automated circuits of amplification and

feedback. An audience coming in at this point would be treated to the

logic, the operating principles, and the functional instruments of music

– just without any musicians. The idea of

By

removing the human dimension from the work, another, almost autonomous,

logic starts to emerge. This is the case with Stephen Cornford

and Matthew Appleby’s ‘Human Separation’ (picture right),

in which the artists create an ensemble of patchwork machines, one

driving a bow across a modified ‘cello, another beating percussively at

the frets of an electric guitar. Once each machine has been put in its

place and the instrument plugged in, the two humans step away, leaving

the noise to build across automated circuits of amplification and

feedback. An audience coming in at this point would be treated to the

logic, the operating principles, and the functional instruments of music

– just without any musicians. The idea of

a

mechanism running away with itself seems also to emerge in Emma

Bennett’s ‘Glistening, dog, daylight (1987)’ (picture right),

a performance which consists mostly of spoken text interrupted by a few

simple actions. Bennett introduces the event, saying, ‘I’m going to do

a thing. I’ve not decided if it’s a thing about a dog, or a thing about

saying “dog”.’ What unfolds is a hypnotic linguistic cut-up which

centres around a few key images: a dog running across a field, a river,

the passage of time. As Bennett speaks, language seems to get away from

its human, social function and take on a restless, circulating energy of

its own – such that, after a while, it doesn’t seem as if Bennett is

speaking, or as if there is a subject at all.

a

mechanism running away with itself seems also to emerge in Emma

Bennett’s ‘Glistening, dog, daylight (1987)’ (picture right),

a performance which consists mostly of spoken text interrupted by a few

simple actions. Bennett introduces the event, saying, ‘I’m going to do

a thing. I’ve not decided if it’s a thing about a dog, or a thing about

saying “dog”.’ What unfolds is a hypnotic linguistic cut-up which

centres around a few key images: a dog running across a field, a river,

the passage of time. As Bennett speaks, language seems to get away from

its human, social function and take on a restless, circulating energy of

its own – such that, after a while, it doesn’t seem as if Bennett is

speaking, or as if there is a subject at all.  actions

speak for themselves, unadorned, matter-of-fact. For ‘Free Cell,

Solitaire, Golf and Pyramids’ (picture below left), Mark

Greenwood spends hour after hour arranging playing cards decorated

with movie stars, cultural icons, sports heroes, and anonymous porn

models. Methodically, without explanatory gesture or illustrative

frame, Greenwood creates a mandala of vice, his own mental state

apparently bending and breaking under the repetitive monotony of his

task. In Charlotte Bean’s ‘Third Time Luckylusting’, the

self-contained ritual reaches suggestively outward in time and space.

Layering slides, sound, and Super 8 film, the line between this

performance event and other events begins to blur, with another

ritualised event visible in the slides, and with Bean attempting to feed

the film loop

actions

speak for themselves, unadorned, matter-of-fact. For ‘Free Cell,

Solitaire, Golf and Pyramids’ (picture below left), Mark

Greenwood spends hour after hour arranging playing cards decorated

with movie stars, cultural icons, sports heroes, and anonymous porn

models. Methodically, without explanatory gesture or illustrative

frame, Greenwood creates a mandala of vice, his own mental state

apparently bending and breaking under the repetitive monotony of his

task. In Charlotte Bean’s ‘Third Time Luckylusting’, the

self-contained ritual reaches suggestively outward in time and space.

Layering slides, sound, and Super 8 film, the line between this

performance event and other events begins to blur, with another

ritualised event visible in the slides, and with Bean attempting to feed

the film loop

For

some of the work in the festival, it is necessary to experience it

evolving and unfolding over time in order to take it in. Others work

with the power of the image, in which all the necessary experience is

immediately apparent, though it may take time to absorb. Sometimes this

power comes through simply the forcefulness of the concept, as in Rob

Boole’s fixed frame video of the artist steadfastly chewing his way

through pieces of raw meat, stopping only to belch or gag, then carrying

on. Other work gains power through a careful control of composition, as

in Mark Greenwood’s work (described above) or in Ula Dajerling’s

tranquil performance of a clothed female body, lying face down on the

For

some of the work in the festival, it is necessary to experience it

evolving and unfolding over time in order to take it in. Others work

with the power of the image, in which all the necessary experience is

immediately apparent, though it may take time to absorb. Sometimes this

power comes through simply the forcefulness of the concept, as in Rob

Boole’s fixed frame video of the artist steadfastly chewing his way

through pieces of raw meat, stopping only to belch or gag, then carrying

on. Other work gains power through a careful control of composition, as

in Mark Greenwood’s work (described above) or in Ula Dajerling’s

tranquil performance of a clothed female body, lying face down on the