|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Portrait (for a screenplay) of Beth Harmon Limoncello, London 27/8/09 – 19/9/09

Who exactly is Beth Harmon? If, like me, you're unfamiliar with Walter Tevis's 1983 novel The Queen's Gambit, it is this tantalizing question that buzzes around your head while exploring this exhibition featuring artists from Bristol, Cardiff and London. Curated by Limoncello artist Sean Edwards, the show is part of a fascinating ongoing project where artists, curators, writers, musicians and even actors are invited to read Tevis's coming-of-age thriller and make responses relating to the young protagonist and chess genius, Beth Harmon. But rather than portraits of Harmon, the works in this exhibition are instead evocations of her character; as Edwards elaborates: “they are studies, notes in the margins, dog eared pages and collected Post-it notes.” Presented on a small tripod-mounted video monitor, Cardiff-based Anthony Shapland's contribution is a film referencing Raymond Cook, an obscure civil servant whose hobby was to carve elaborate miniature sculptures from matchsticks. A brief appearance on Blue Peter in the 1970s brought him to Shapland's attention, although he soon slipped back into obscurity and his achievements have been largely ignored until now. Shapland draws parallels between Cook and Harmon; they are both obsessive, driven and gifted, yet, unlike Tevis's creation, Cook was a real man. The Life of Raymond C. Cook (Title Sequence) (2009) presents a tabletop workshop, an imagined environment created by a television props manager. Stacks of match boxes litter the table along with various tools that Cook may have used to create his miniature marvels. As the camera pans across the scene we notice a video monitor in the background, revealing the tableau to be a televisual construct: pure conjecture created for a documentary that is yet to be produced.

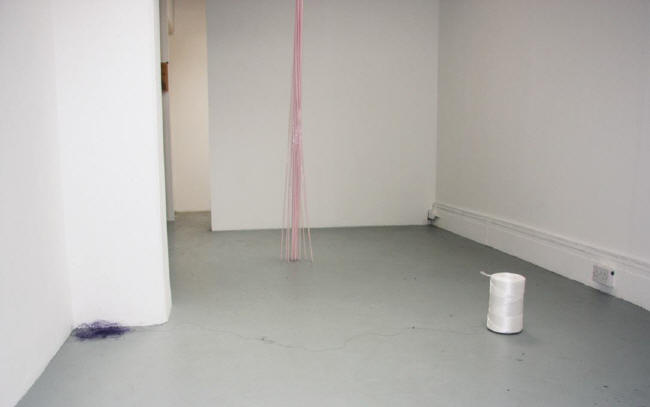

Sitting nearby on the floor, Sara MacKillop's characteristically slight contribution, String Piece (2009), comprises a large spool of string. Inside this sits a smaller cotton reel which has become unravelled; its blue thread sprawls across the gallery floor ending in a tangled heap. Upon reading the novel, MacKillop became intrigued by the way Beth Harmon organises elements of her life, attempting to compartmentalise daily activities, such as chess or drinking. MacKillop links this to the systems of organisation that exist within everyday materials, such as the overlooked patterns formed by wound string, or unravelled thread. This subtle, unassuming work may itself pass largely unnoticed, and although the connection with Harmon seems somewhat tenuous here, the formal economy of MacKillop's work is enjoyable as ever.

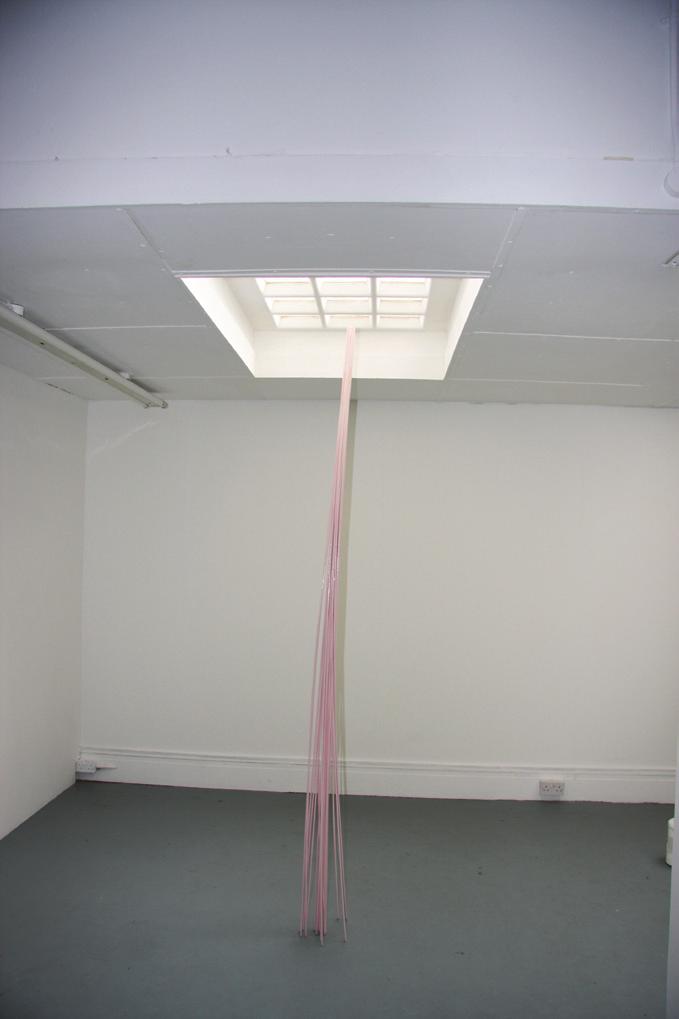

More abstruse is Natasha Macvoy's gangly sculpture I Love Lucy (2009). A bundle of long, pink wooden canes stands precariously upright, looking as if it might topple at any moment. The work follows the same form as many of the Bristol-based artist's recent works, which suggests her ideas have been somewhat shoehorned here to fit the exhibition's curatorial agenda. Nevertheless, MacVoy's slender structure borrows its title from a book read by Beth Harmon in the novel, which coincides with the introduction of another character, Jolene. The relationship between these two characters is the only one in which Harmon does not appear to have total control. The ensuing tension and unsettling potential for disaster is reflected in MacVoy's work, which itself teeters on the edge of collapse.

The most intriguing piece here is Paul Corcoran's sculpture A War Aid as a War Game (2009), in which the artist has taken a 1942 Eames leg splint and refashioned it into a rudimentary chess set. Cut in to 32 pieces of varying size, each fragment has been labelled with a single black or white stripe. Displayed under glass in a custom built box, the work has the air of a valuable museum exhibit or archived artefact. Quite how you're meant to play with this set is unclear, although Corcoran managed to beat curator Sean Edwards in a game before the show's opening. In that game, which is documented on the adjacent wall, Edwards opened with the Queen's Gambit, the move ‒ after which Tevis's novel is named ‒ where one player offers to give up a pawn in the expectation of gaining a positional advantage. In the novel, chess virtuoso Harmon was able to accurately anticipate her opponent's moves and develop strategies to exploit their weaknesses. The fragmented splint reflects the way in which chess, which initially acts as a support structure to Harmon, leads her into a heady world of alcoholism and tranquilliser addiction where her life starts to collapse.

So, who is Beth Harmon? Based on the strength of the individual pieces here, I'm not sure that it really matters. Before the show opened this was also a concern for Edwards, who in an imaginary conversation with the show itself (included in the gallery guide) confesses: “I'm worried about how much the audience need to know about the book; about Beth Harmon”. Fortunately for Edwards the answer is not very much, for each compelling work here stands on its own merit regardless of one's familiarity with The Queen's Gambit. However, the exhibition is bound to pique interest in the novel and those who take time to read it will no doubt find their experience of Edward's project significantly enriched.

David Trigg 29/9/09

|

|

|