|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

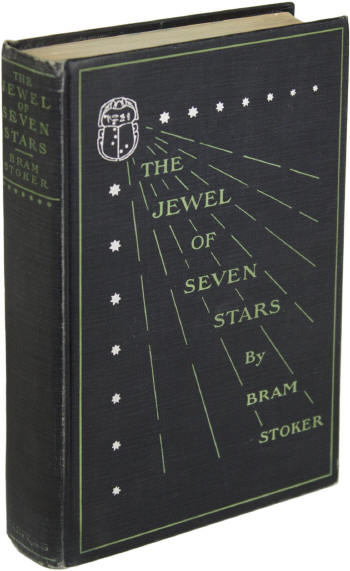

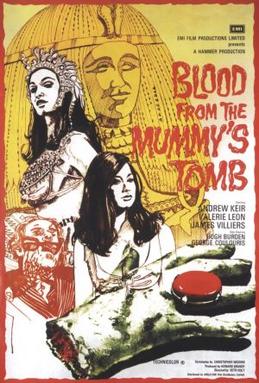

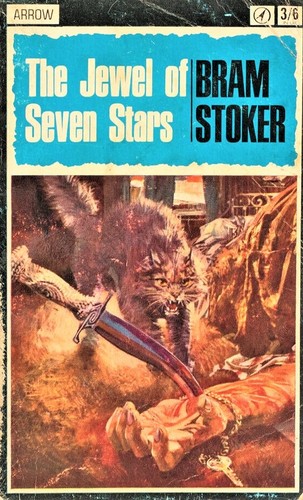

The Mummy's Hand Shelley Trower An analysis of Bram Stoker's 'The Jewel of Seven Stars' (1903). From 'Rocks of Nation' (2015).

Whether the movement is outwards towards the exotic or in the reverse direction, usually England and its 'Other' are, at least initially, sharply opposed. The English explorer may undergo the process of going native', 5 but the very possibility depends at the outset on the perception of an essential difference that is then subject to challenge or collapse. Cornwall, however, complicates this relation between England and those regions perceived as foreign, as this county is of course part of the English nation at the same time as it is often perceived as being distinctively 'Celtic'. Critics have previously focused on 'Celtic' places that are more clearly differentiated from England, considering Stoker's and Conan Doyle's relations to Ireland and Scotland. 6 While Ireland and Scotland became part of the United Kingdom with the Acts of Union in 1800 and 1707 respectively, they have never been part of England. There are many similarities, however, in the way these authors depict Ireland, Scotland and Cornwall: the 'geographical doubling', which David Glover identifies in Stoker's depictions of Ireland and Transylvania, for example, can again be found in his depictions of Cornwall and Egypt, all of which are perceived at times as foreign from the perspective of the English traveller.7 R. L. Stevenson similarly developed comparisons between Scotland and the Pacific islands, especially between the fate of their natives, as Robert Peckham observes 8, while on his travels through America he perceives the Cornish emigrants as entirely different from their English neighbours at home. For Stevenson, though, the Cornish seem incomparable to anyone: 'Not even a Red Indian seems more foreign in my eyes. This is one of the lessons of travel - that some of the strangest races dwell next door to you at home' 9 Stevenson here highlights the paradox that Cornwall is part of England and yet its natives seem more foreign than those overseas. Cornwall, then, with its potential to figure as foreign while it is also an English county, serves both as the outlying destination for the English explorer, or tourist, who typically heads out from the urban centre that is London, and as a space where England might be especially susceptible to invasion from elsewhere. The Cornish cliffs operate as an ambiguous space, a permeable border at the edge of England that serves as both a point of destination and infiltration. In The Jewel of Seven Stars the journeys outwards are to Egypt and to Cornwall, while Cornwall is in turn invaded by Egypt. The journey to Egypt is taken in the narrative's past, the leading explorer being Mr Trelawny who brought back various objects including an Egyptian mummy, that of Queen Tera. Mr Trelawny and his circle, including his daughter, Margaret, and Margaret's devoted admirer, our narrator Malcolm Ross, later make the journey from London to Cornwall as this is a relatively isolated place where the 'Great Experiment', the resurrection of the mummy, can be carried out. Ross briefly describes the overnight train journey, which departs from London, to the south-west peninsula. During this journey a minor incident occurs on the coast where a small landslip causes a delay, while Margaret begins to behave strangely (later we learn that she is being possessed by the Egyptian queen), occasionally recovering herself 'when there occurred some marked episode in the journey, such as stopping at a station, or when the thunderous rumble of crossing a viaduct woke the echoes of the hills or cliffs around us' 10 In this way the reader is given the sense of a distance being crossed, and of the progress through new places - through the echoing sounds of their geology - towards an adventure far from the city. Although this journey is shorter and involves less excitement than the earlier explorations in Egypt, the resemblance between the two outlying locations, where the key supernatural scenes take place, soon becomes clear. The Egyptian and the Cornish locations are both isolated and rocky, situated on a steep cliff, in a secret, ancient cave. Having travelled to the far edge of England, Malcolm describes his first sight of the 'great grey stone' Cornish mansion, on the very verge of a high cliff', and a little later the position of the dining room, its walls hanging right over the sea: We were all impressed by the house as it appeared in the bright moonlight. A great grey stone mansion of the Jacobean period; vast and spacious, standing high over the sea on the very verge of a high cliff. When we had swept round the curve of the avenue cut through the rock, and come out on the high plateau on which the house stood, the crash and murmur of waves breaking against rock far below us came with an invigorating breath of moist sea air. [...] We had supper in the great dining-room on the south side, the walls of which actually hung over the sea. The murmur came up muffled, but it never ceased. As the little promontory stood well out into the sea, the northern side of the house was open; and the ree orch wabin no way hote by the great mass of rock, which, the bay we could see the trembling lights of the castle, and here and there along the shore the faint light of a fisher's window. For the rest the sea was a dark blue plain with here and there a flicker of light as the gleam of starlight fell on the slope of a swelling wave.11

Teetering on, or just beyond, the very edge of England, such locations offer a space that is felt to be almost detached from the nation, to overlap with distant places overseas. Much as the explorers in Egypt had to climb up a cliff and find the entrance to the cave, a tomb into which they descended to find the treasures and mummy, in Cornwall the hidden house on the cliff contains a secret cave, previously used for smuggling, into which the explorers descend. Mr Trelawny explains that he has chosen this spot for the resurrection of Queen Tera's mummy, at least partly because of its similarity to the Egyptian location: 'In a hundred different ways it fulfils the conditions which I am led to believe are primary with regard to success. Here, we are, and shall be, as isolated as Queen Tera herself would have been in her rocky tomb in the Valley of the Sorcerer, and still in a rocky cavern'.12 The special properties

of granite provide another similarity between the two locations in Egypt

and Cornwall. Mr Trelawny speculates that radium - a radioactive

element, which early twentieth-century physicists were beginning to

understand, most commonly found in granite 13 - may make the

resurrection possible, as it is a kind of energy that is

'heat-giving, light-giving - perhaps life-giving' 14. He

claims that it is very likely that radium exists in Egypt, because of

its large quantities of granite, and that it may have been

known to the ancient Egyptians. Granite and its 'decomposed' form as

clay or kaolin has been quarried in Cornwall , but in Egypt granite

apparently exists in even greater proportions: 'That country has

perhaps the greatest masses of granite to be found in the world; and

pitchblende [a uranium ore that is mingled with other radioactive metals

such as radium] is found as a vein in granitic rocks. In no place, at no

time, has granite ever been quarried in such proportions as in Egypt

during the earlier dynasties.' 15 The movement of the explorers outwards, then, are to two locations perceived as exotic - Egypt and Cornwall - and this movement is paralleled by the invasive movement often described as 'reverse colonisation'. Cornwall functions as an exotic location but also as part of England, with the potential to be invaded or otherwise disturbed by an alien culture. Mr Trelawny's large collection of Egyptian artefacts, like other collections in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, clearly helps to contribute to his image as a triumphant imperial explorer, but as Erika Rappaport has recently observed, in the context of the instability and dangers associated with imperialism in late-century gothic, objects like the mummy occasionally come to life and grab back'. 16 Thus while Mr Trelawny has taken possession of the Egyptian goods, he begins to lose a degree of control as the Egyptian Queen seems in turn to take possession of his daughter, who becomes increasingly strange to our narrator. Egypt begins to enter Cornwall in an increasingly overpowering, supernatural and disturbing way. Malcolm goes out for a stroll on the clifts to think over Margaret's strangeness, and concludes that 'in some occult way the Sorceress [the mummified Queen Tera] had power to change places with the other'. 17 The collapse of space brought about by the Queen's 'astral body' becomes increasingly prominent as Margaret loses possession of herself, and the Cornish cave in the closing chapter is finally, it seems, lost to the dangerous presence of the foreign land. Though there are two different endings (Stoker revised the original for republication in 1912), in both, crucially, a mysterious Egyptian miasma - a 'faint greenish vapour' or 'smoke', with a 'strange, pungent odour' 18 - fills the Cornish cave, becoming so dense as to obliterate vision and to overpower the witnesses. In the 1903 edition the filling of the room with smoke corresponds climactically with the shaking of the cliff below the house as though the land of Cornwall is in danger of falling apart, of becoming altogether detached from the nation of England, of collapsing into the sea: 'The storm still thundered round the house, and I could feel the rock on which it was built tremble under the furious onslaught of the waves." 19 Similarly in Basil, we have seen how the shaking of the rocks is accompanied by a loss of vision, in that case due to the thick mist, contributing to the victim's sense of passive powerlessness as he can feel the ground fall apart under his feet while he lacks the ability to control his situation. At this point in The Jewel - the narrator can just about see in a now blinding light - the mummy's hand appears to rise in a white mist. But the stormy wind then breaks through the window causing the vapour to drift from its course. Smoke fills the room so that the narrator can no longer see at all, and when he eventually finds his companions they are all dead. In the later version the smoke again becomes denser and denser, obliterating the light and producing a darkness which the narrator here interestingly calls 'the Egyptian darkness' 20 Again the presence of Egypt in these climactic scenes seems dangerously to overwhelm the space of the cave, a space that already seemed far removed from England. In this revised ending the results of the experiment are left uncertain, but Margaret survives and there is the hint that the Queen was resurrected and might continue to live on as part of her. In Dracula the initial invasion of the alien similarly takes place as close to the cliff edge as possible, in a graveyard that 'descends so steeply over the harbour that part of the bank has fallen away, and some of the graves have been destroyed'. 21 This is Mina's favourite spot, where she sits as the storm approaches, bringing with it the foreign ship. As she watches, the line between land and sea, and sky, is blurred even further, becoming lost in an equalising greyness that colours everything from rock to clouds to sea to sand: 'Everything is grey - except the green grass, which seems like emerald amongst it; grey earthy rock; grey clouds, tinged with the sunburst at the far edge, hang over the grey sea, into which the sand-points stretch like grey fingers'. And with the stormy greyness a mist begins to enter England, further blurring and then erasing the difference between sea and the wet sky that becomes so dense it resembles solid land: 'The horizon is lost in a grey mist. All is vastness; the clouds are piled up like giant rocks.' 22 The masses of fog then drift inland, obliterating vision like in the Cornish cave, leaving 'only the organ of hearing' to sense the violence of the storm. Out of this darkness springs the alien creature - the wolf - much as the mummy's hand rises out of the mist, and heads straight towards the point on the projecting cliff: The very instant the shore was touched, an immense dog sprang up on deck from below, as if shot up by the concussion, and running forward, jumped from the bow onto the sand. Making straight for the steep cliff, where the churchyard hangs over the laneway to the East Pier so steeply that some of the flat tombstones — 'thruff-steans' or 'through-stones', as they call them in the Whitby vernacular - actually project over where the sustaining cliff has fallen away, it disappeared in the darkness.23

As Nancy Armstrong points out, focusing on Emily Bronte's Wuthering Heights - also set in Yorkshire (further to the west) - nineteenth-century fiction and folklore took part in a regional mapping of Britain that divided it into a literate urban centre and a 'Celtic or ethnic periphery'.27 Novelists and folklorists described the English countryside as marginal in ways that resembled foreign nations, which the tourist industry selectively incorporated into its own narratives. Armstrong points to some of the similarities between British colonial attitudes towards Africa and Asia and the voyeuristic gaze of a narrator-tourist such as Lockwood in Wuthering Heights, who documents and classifies the natives as primitive, while also romanticising them. Similar characteristics of the travel narrative in Dracula are apparent with Mina's detailed accounts of her new surroundings and the dialect-speaking 'natives' (echoing Jonathan's earlier accounts of Romania), while The Jewel provides us with a more developed sense of an imperial adventure into regional difference with its more eventful train journey to Cornwall, followed by the narrator's detailed description of the scenery, the house on the cliffs with its Egyptian cave, and his Cornish lover/Egyptian Queen. In The Jewel the peripheral region is described, as I have said, not just as different from England but as closely resembling Egypt, before being invaded by its atmosphere to the extent that it becomes indistinguishable. It is as if the mini-imperial journeys are finally magnified into the real thing: our narrators become immersed absolutely in the alien atmospheres.

5.6.25 |

|

|

Stoker

builds on these scenes at Whitby for The Jewel, relocating the

point of foreign invasion in Cornwall where he further develops the

sense of difference from (the rest of) England. With the 'Whitby

vernacular' here, which the locals speak in at some length 24, we

get some sense of Whitby's distinctiveness. Yorkshire's regionalism is

comparable to some extent to that of Cornwall: it is similarly distant

from the urban centre, with its own landscapes and legends and dialects,

and it provides an escape for tourists.25 But Mina's journey

hardly constitutes the mini-imperial adventure that is seen in The Jewel

- we hear nothing more of it than 'Lucy met me at the station'

26 - while there are hints in her following account of the local

scenery, history and folklore about the regional difference that is

exploited more fully in Stoker's later novel.

Stoker

builds on these scenes at Whitby for The Jewel, relocating the

point of foreign invasion in Cornwall where he further develops the

sense of difference from (the rest of) England. With the 'Whitby

vernacular' here, which the locals speak in at some length 24, we

get some sense of Whitby's distinctiveness. Yorkshire's regionalism is

comparable to some extent to that of Cornwall: it is similarly distant

from the urban centre, with its own landscapes and legends and dialects,

and it provides an escape for tourists.25 But Mina's journey

hardly constitutes the mini-imperial adventure that is seen in The Jewel

- we hear nothing more of it than 'Lucy met me at the station'

26 - while there are hints in her following account of the local

scenery, history and folklore about the regional difference that is

exploited more fully in Stoker's later novel.