| artcornwall | |||

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | gazetteer | links | archive | forum | |||

|

Peter Fluck: Cornish artist and co-founder of 'Spitting Image' Peter Fluck is known to many as the man, who with his partner, Roger Law, was behind the hugely successful TV show 'Spitting Image'. Trained originally as an artist, he is now working and exhibiting as an artist in Cornwall and, with his wife had a show at Vitreous Contemporary Art in the Summer 2005.

Peter, can we start with some early biography? What part of the world did you grow up in? What sort of a childhood was it and was art important to you as a boy? In the 1920s my father worked for large country estates, first as a gardener’s boy, later moving on to be in charge of hothouses. He became expert at doing weird stuff out of season, fresh grapes at Christmas, apples on trees for the ballroom in February. All this came to an end with the Depression, putting both my parents out of work for some time. After a series of odd jobs my father was finally appointed head gardener at Magdalene College, Cambridge in about 1935. I was born in 1941. I went through Infant, Primary and Grammar school education in Cambridge enjoying a childhood in the brand new outer suburbs – edging on the town but also onto allotments, orchards and the Fens. This proximity of country and university was wonderful for my boyhood fascination with ornithology. When I wasn’t up to my knees in a dyke I was in the University’s Museum of Zoology staring at and drawing the stuffed birds. At Grammar school, after a huge effort I achieved four rather miserable 'O'-levels. My parents and masters both agreed that the best and only prospect would be a course at Cambridge School of Art, who after studying my folder of drawings of house sparrows, accepted me.

How was art school, and how was it that you became interested in caricature? Art School

was a wonderfully exotic environment for a 16yr old from suburbia. But 2

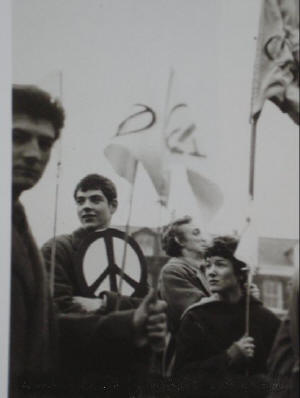

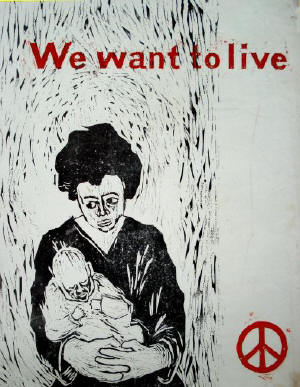

years of life Sometime around the late fifties, change came along. Design became all-important, leading to an awareness of the Bauhaus work and teaching. Tutors changed, bringing a different focus. One part-time teacher was particularly important to myself and also to my best mate at art school, Roger Law. Paul Hogarth an artist reporter and illustrator, ex-communist but still extremely left wing artist had travelled to South Africa, Russia, China and Poland, making brilliant reportage drawings on the spot. He came to Cambridge on Wednesdays and Thursdays. His knowledge of leftist biased artists in the near past and the romance of his own small part in the Spanish Civil War helped to guide us into the politicised 1960s. Roger and I developed an interest in the work of the European immigrant artists who flooded into Paris in the early 1900s and that of the German Expressionists, especially George Grosz. This was the beginning of our interest and involvement with caricature. Along with this focus came CND, the principles behind which we had great enthusiasm for. We did wood cuts for posters, printed them (picture below left), we designed pamphlets, distributed them, we demonstrated and marched (picture above: 1958 Aldermaston march).

So your interest in caricature was linked with political activism from the start, by the sound of it. The two of you went on to become the creators of Spitting Image, that well-loved satirical show that ran on prime time TV for over 10 years. What led up to its first airing in 1984 and how did you share the work out? In Cambridge we got to know Peter Cook who through the Footlights and friends was beginning to evolve a new contemporary satire. It was his thinking that was the initial influence behind Beyond the Fringe, Private Eye, David Frost’s That was the Week that Was and later the Establishment Club in Soho.

After Art school in Cambridge, the need to further our careers meant a move to London. Roger and I both set up as freelance illustrators. We were fortunate in that our move coincided with the emergence of the first sophisticated glossy magazines and the first colour sections in quality weekend papers all employing talented and dedicated writers and with editors interested in using illustrators and designers In the early seventies both Roger and I were working in 3D for 2D reproduction. Instead of drawing or painting a caricature, a model was made in plasticine which was then photographed, the picture becoming the art work for the illustration. This gave the advantage of the cameraman’s skills being added to our work – colour lighting perspective and atmosphere. The resulting caricatures, through this process, had a greater presence on the page than our previous graphic work. In 1976 we decided to work together and set up a partnership “Luck & Flaw”. Based back in Cambridge we worked out of a defunct Temperance Mission (the pub next door is still there). We shared the work straight down the middle both able to do all that was necessary. It soon became clear that with some money and even more ingenuity the static caricatures could become puppets. The idea of Spitting Image was conceived. Delivering the baby was a longer haul. We had to locate and enthuse sculptors, mould makers, painters, costume designers and makers, prosthetic technicians engineers, runners, gophers and coffee makers to populate a workshop to supply the rapacious needs of the producer, directors, writers and the script editor who in turn were working with the puppeteers, voiceover artists and a huge studio crew. So, yes Roger and myself did create the show and worked together as much as possible. I was much better than Roger at solving “puppet” problems and he better at being the big man with the huge drum in the cartoons of Roman galleys. It was a show that was very complex and demanded a lot of its staff, but as you say, immensely popular. We went into television without knowing anything about it and came out extremely tired! It ran with a huge audience from 1984 to 1996, showing at the difficult time of 10 o‘clock on a Sunday night when all politicians should have been in bed. It is also very pleasing that people we employed in our caricature factory went on to became top professionals in their own right.

Looking back now what do you see as the legacy of Spitting Image? It must

have helped the Because of its inherent complexity Spitting Image needed to train and employ talent and ability from all over the creative spectrum, from technical specialists to artists, musicians, puppeteers and voice artists. From 1984 to 1996 and after 146 half hour episodes plus many specials, the puppets were finally sentenced to eternal storage. The crew and cast however, went on to work for and to run many of the currently successful comedy shows - Red Dwarf, The League of Gentlemen, Little Britain, Rory Bremner and the The Royle Family. Many of the visual and practical staff are multidisciplinary in animatronics, animation, software, product design and engineering worldwide. And I believe that they have kept the standards and attitudes which made the programme possible [encouraged by enormous wages !] If we left a legacy at all, I think it was this. Here are just a few of the names who passed through the payroll: Jon BlairJohn LloydTony HendraDavid TylerBill DareChris BarrieRory BremnerSteve CooganHugh DennisLouise GoldHarry EnfieldJon GloverSteve NallonJan RavensEnn ReitelJohn SessionsIan HislopNick NewmanRob Grant and Doug NaylorJack DohertyGuy JenkinAlistair BeatonJohn O`FarrellSteve PunAlistair McGowanGeoffrey PerkinsPeter HarrisBob CousinsJohn StroudJohn HendersonSteve BendelackAndy de EmmonyLiddy OldroydPhil PopeGeoff Atkinson

Some viewers exposed to the show for 12 years could perhaps have developed a certain cynicism about politicians, preparing them for New Labour’s spin.

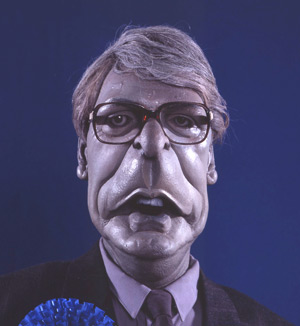

I think that if we had been on the air during the emergence of New Labour in 96-97 we would had a wonderful time, with as much material as Thatcher and the vegetables gave us. I think that one thing that made our caricatures seem savage was the contribution made by the voice artists. Thatcher’s voice by Steve Nallon and Chris Barrie’s impersonation of Reagan illustrate this well. The weakness of the Major Government was, it seemed to me, because they had John Major as leader. Although I suppose we actually didn’t do him a lot of good by showing him eating peas every night and making him completely grey. Being seen as a disastrously sad figure on Sunday nights by an audience of 10 million and more is not the way to get your statue in Parliament Square. I think that what brought that government down was that people didn’t know if they had a leader or not. The show always had to have enormous audiences because it had to justify its huge expenditure. From the very beginning Central TV hyped the show mercilessly to the whole of Fleet street, releasing pictures of puppets to the papers as soon as they were made and encouraging sub-headlines – “ Look what they’ve done to our Queen!!!!!” etc. Very tedious but it worked to launch the show. Interestingly it was the size of the viewing figures that made us include a lot of material about sport and popstars. Roger and I didn’t really enthuse over that too much but it did mean that the political content got to far more people than if we’d had a purely political show.

Moving to your life now: what brought you to Cornwall and how have you found it since youve been here? Anne-Cecile de Bruyne, my wife (who I met at Cambridge Art School, now a painter) first introduced me to Cornwall in 1960. Her parents owned a house near The Lizard. This is where we live now, on top of a cliff in a working fishing village. Typical of these coastal communities, the place has all the drama and warmth you would expect. I find Cornwall very much as my first experience of it. A very beautiful and superb place to live. I enjoy seeing Cornwall working out of its historical poverty and benefiting from The Tate St Ives, The Eden Project and most important the new university at Tremough.

Am I correct that one of your mobiles is at the Eden Project? I think they’re very beautiful. I often wonder why there has n’t been more kinetic art made down here: and something that responds to the wind like this seems especially poetic and appropriate. I was asked

by the Eden project to present a design for a wind driven landmark piece,

which was The Mobiles are created with the intention of their being simple in their movement and in both form and construction. I concentrate on two basic types – wind driven and motorised, which share the same starting point. They are all based on Chaos Theory. Although their movements are similar, their behaviour is not predictable. This is because they are made up of freewheeling components whose movement is caused by energy from the centre or from energy returning to that centre from momentum generated at the peripheries. This is why they usually have a certain fractal form and often relate to tree forms. One aspect and probably the most important thing about mobiles is that they exist and perform in Time – perhaps the most important thing I learnt from television. The type of construction I use makes for the most effective choreography, allowing the viewer to spend time experiencing the quiet surprises produced. One of the most gratifying pieces was made for the Tate St Ives in 1997. A collaboration with Dr Tony Myatt, director of The Music Research Centre, which is part of the music department of the University of York. The movements of the mobile were tracked through a video camera feeding into a computer. The images were tracked with the aid of colour recognition software. This information of movement then triggered musical algorithms of the composer’s choice, producing a continuous flow of musical compositions. The piece “Chaotic Constructions” ran for three months, developing movement and sound in real time. I also have wondered why more mobile work hasn’t been done in Cornwall but I‘ve asked the same question of early Modernism in Russia at the beginning of the 20th C. I think that possibly artists either don‘t have, or don‘t want to develop, the fabrication skills needed, although I think that engineering is a very valid art medium.

That Tate piece sounds fascinating. Sorry I missed it. What about your other work? I understand you’re working in a range of media…

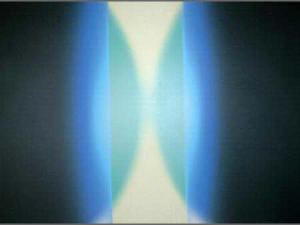

A little while ago I returned to the experience we gained from the work we did in photographic studios, to experiment with light and colour for their own sake. To do this I constructed simple abstract architectures from white paper and card projected light and colour onto them (above). Using light instead of pigment is a challenge as the primary colours are not the same. After days of change and adjustment they were photographed then made into digital prints.

The mobiles, and some of your 2D work, seems to relate to early St Ives art (especially Gabo’s brand of Russian constructivism) and therefore to a local tradition of abstract art-making. Would you agree with this? You’re right about St Ives but you’d be even more right about the Russian Suprematist and Modernist movements, and of the Bauhaus. The abstraction is not a locally based influence. It’s to dispel references to “picture making”. When Spitting Image had to go into its coffin, I used it as an opportunity to reinvent myself. And as all the work done previously had, from early days at Art School had been in some way been representational, Abstraction offered a welcome challenge - and still does.

Peters own website is very informative and includes moving images of his mobiles: www.peterfluck.co.uk

RW December 2006

|

|||

I’m

sure that if the programme was running now the politicos would still be

sending in voice tapes and photos of themselves in order to encourage a

puppet of themselves to be made, as they did in the past. A politician

without a puppet was not a success. This reflects one interesting aspect

of the show. It did, of course, because of who the British are, become a

part of the Establishment. Hansard bought a tape of each episode for

members to view at Westminister.

I’m

sure that if the programme was running now the politicos would still be

sending in voice tapes and photos of themselves in order to encourage a

puppet of themselves to be made, as they did in the past. A politician

without a puppet was not a success. This reflects one interesting aspect

of the show. It did, of course, because of who the British are, become a

part of the Establishment. Hansard bought a tape of each episode for

members to view at Westminister.