| artcornwall | |||

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive |forumes | |||

Roger Hilton and the fall and rise of the female nudeTate St Ives Autumn 2006

There are many ways to judge an artistís importance. Probably the most reliable and immediate is to consider their workís popularity with the public. In the case of a gallery like the Tate, that means its ability to pull in an audience, and to a certain extent, shift merchandise.

Hiltonís art, as shown in St Ives in Autumn 2006, is notable for having a narrow range of concerns. These are primarily formal, and linked to the relationship between eroticism, as embodied in the female nude, and abstract painting.

Whilst abstract painting has

pretty much remained a constant since the beginning of the last century,

the depiction of the female nude has been a contested area for several

decades: very sensitive to the vicissitudes of sexual politics, which have

shifted year by year. Hiltonís own influence has waxed

and waned as a result.

In the forties and fifties when Hilton and most of the other St Ives artists came to prominence, much international art was drab and anguished, influenced to be so by existentialism and the aftermath of the second world war. Images of women that were in the least bit erotic were few and far between. Frost, Lanyon and Hilton in their different ways injected a note of optimism and energy into post-war abstraction, which, given Hilton's Dionysian impulses, led naturally to his joyful depictions of women (picture above), which at times bordered on the scatological and pornographic. In some ways, in retrospect, he can be seen to have been kicking against the respectable Apollonian qualities conspicuous in many of the other St Ives artists, and was introducing overt images of women into his work around the same time as Tom Wesselmanís American nude series in the states, and Allen Jonesí fetishistic pop in the UK.

There was, however a tidal-wave of

male artistís images of the female nude in the

Like Hilton there was, for many of

them, a link between sexuality and luscious and slightly fevered paint

handling Ė certainly in the case of

These shifts in taste and perception, which have really occurred in the few years that Tate St Ives has been open, have allowed us to look at Hilton again with less embarrassment or guilt, and recognise strong links between his own aesthetic and that of a number of artists of our own time.

However Hiltons work shares less

with contemporary depictions of the female nude than appears at first

glance. Contemporary male artists do not tend to paint from life but are

more likely to borrow images of women from

magazines or the internet. In the

process these women become larger than life:

Whatever the reason, and

considering the Hiltonís show at Tate St Ives this Autumn, it was

therefore not other male artists who came to mind, but female artists who

seem to be better able to depict the nude with the frankness and immediacy

that comes with drawing

Why not respond to this article on the forum?...

|

|||

Longer-term

importance would seem to hinge more on an artistís influence on younger

generations of artists Ė and such longevity in turn depends on the extent

to which the work is able to survive ever-changing views about what art is

or should be.

Longer-term

importance would seem to hinge more on an artistís influence on younger

generations of artists Ė and such longevity in turn depends on the extent

to which the work is able to survive ever-changing views about what art is

or should be.

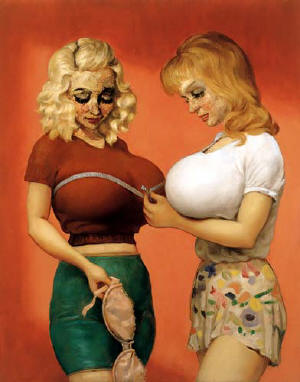

90s. What had been repressed during two theory-laden decades, returned in

ways that were even more aggressively sexual than 60s pop-art, influenced

by the increasingly pervasive presence of porn, and also by a need

perceived on the part of artists to sensationalise and thereby draw

attention to their work. Richard Prince appropriated images of bikerís

girlfriends for his famous photoseries, Marcus Harvey painted rather

misogynistic images of Ďreaders- wivesí (above), Chris Ofiliís

depicted a black virgin mary (right), and John Currin painted women

with impossibly large breasts (below). All used sexualised images

of women with greater or lesser degrees of irony and self-consciousness.

90s. What had been repressed during two theory-laden decades, returned in

ways that were even more aggressively sexual than 60s pop-art, influenced

by the increasingly pervasive presence of porn, and also by a need

perceived on the part of artists to sensationalise and thereby draw

attention to their work. Richard Prince appropriated images of bikerís

girlfriends for his famous photoseries, Marcus Harvey painted rather

misogynistic images of Ďreaders- wivesí (above), Chris Ofiliís

depicted a black virgin mary (right), and John Currin painted women

with impossibly large breasts (below). All used sexualised images

of women with greater or lesser degrees of irony and self-consciousness.

Ďfrom

lifeí. The exemplar here is Tracy Emin (left). Tracys confessional

work, especially her etchings, with their impoverished diaristic sexual

content, seem to be very close in spirit to Hiltonís drawings Ė

particularly the series in the Apse, and to his late gouaches. In fact

both also draw on a deep well of humanity, in the form of biography and

lived experience, that is lacking in much contemporary art.

Ďfrom

lifeí. The exemplar here is Tracy Emin (left). Tracys confessional

work, especially her etchings, with their impoverished diaristic sexual

content, seem to be very close in spirit to Hiltonís drawings Ė

particularly the series in the Apse, and to his late gouaches. In fact

both also draw on a deep well of humanity, in the form of biography and

lived experience, that is lacking in much contemporary art.