|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Satyrs and sigils: the artist-occultist Austin Osman Spare By Paul Newman. Written in response to 'The Dark Monarch' at Tate St Ives.

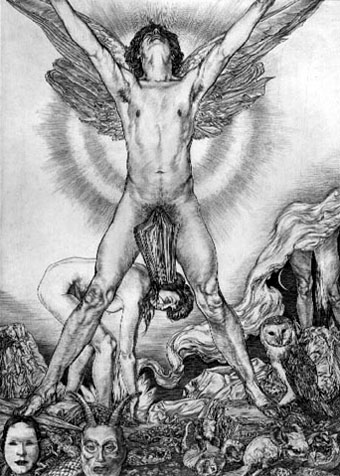

Few pre-war artists could be classed as ‘pagans’ although many espoused a more natural way of life and an open attitude to relationships. The founding of the Golden Dawn and other mystical organisations marked a Late Victorian and Early Edwardian revival of interest in occultism, offering techniques for using tarot cards, the cabala and contacting or drawing down angels, entities and archetypes.

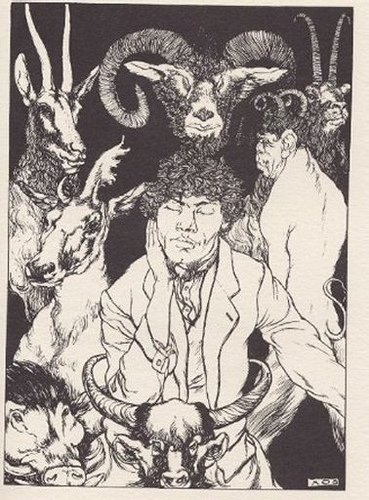

The comparison is merited, save Spare lacked Beardsley’s playfulness and the ability to frame an elegant sexual insinuation. Spare’s satyrs are depicted - mildly satirically - in comfortable settings and pursuing respectable vocations. One is aware of an aggressive vitality energising a line that is informed by a quality not easy to define. It would be crude to say the characters seem ‘possessed’ but there is a sunken selfishness in their expressions. Their stares seem to exclude everything save for a secret focus or want. Of course, more than a little of the artist is hidden there. Spare’s existence was a claustrophobic tunnel of self-exploration. And he did not think of the satyrs and spirits he drew as fantasies but as records of those he encountered in his daily life. “These beings,” a critic wrote, “live…in their horned horror in the drab streets south of London Bridge. The ribaldry and coarse revelry of the slums is due to the influence of these beings of the Borderland, [Spare] believes.” Whether whoring, taking drugs or plunging into orgies, it was all in the interest of attaining magical mastery. Some of Spare’s designs have an explicit sexuality that, back in those more thrilling times, brought the flat-footed constable with notebook and gleaming eye knocking on the door. Others are as phantasmal and flesh-creeping as anything out of Gustav Meyrink, pools and eddies of misty spirit-substance out of which faces peer, starved, bloated, mean-eyed or horribly misshapen. In 'The Dark Monarch' (Tate St Ives, 2009), The Qliphoth, for example, portrays a kaleidoscopic fog of faces, shells and remnants of dead souls, but the colours are wild, inspiring, fresh as pebbles on the beach, like brilliant incarnations rather than burnt-out cases.

Did it work? Pragmatically speaking, it served Spare well. Persistent inner-journeying and obsessing on minutiae fired his drawing and painting. Within such a self-fuelling, insular environment, any bolt from the blue – a visit from an attractive person or generous cheque from a patron – arrived on the scene like a dramatic fulfilment of desire. If you immerse yourself as powerfully as Spare did, the great without will inevitably warp to the shape of your perception. |

|

|

During

this period, probably the most effective occult artist practising in

Britain was Austin Osman Spare. His early work The Book of Satyrs

invoked comparison with Aubrey Beardsley with whose sister Spare had

once enjoyed an intimate relationship.

During

this period, probably the most effective occult artist practising in

Britain was Austin Osman Spare. His early work The Book of Satyrs

invoked comparison with Aubrey Beardsley with whose sister Spare had

once enjoyed an intimate relationship.  Spare

masterminded a magical system known as ‘chaos magic’ that struck other

magicians as dangerous and heretical: hence it has become increasingly

popular. In the past, those who believed magic worked tried to achieve a

desire by concentrating on whatever it was, aligning it with a colour,

texture, date, deity and other correspondences that would be

co-ordinated in a ritual. The object would be theoretically drawn by

these ‘sympathetic’ magnets. This process was too simplistic and

routinely ritualistic for Spare. His method of achieving a desire was by

first expressing it magically by means of sigil, a self-made object,

usually a drawing and then frenziedly concentrating on it, narrowing his

beam of attention until it was the only thing he perceived. After that,

he’d abruptly throw it aside and make himself forget it. He utterly

detached himself, blanking out all memory, thus achieving an exhausted

forgetfulness and charging the sigil with the energy of ‘free belief’,

thus sealing its potency.

Spare

masterminded a magical system known as ‘chaos magic’ that struck other

magicians as dangerous and heretical: hence it has become increasingly

popular. In the past, those who believed magic worked tried to achieve a

desire by concentrating on whatever it was, aligning it with a colour,

texture, date, deity and other correspondences that would be

co-ordinated in a ritual. The object would be theoretically drawn by

these ‘sympathetic’ magnets. This process was too simplistic and

routinely ritualistic for Spare. His method of achieving a desire was by

first expressing it magically by means of sigil, a self-made object,

usually a drawing and then frenziedly concentrating on it, narrowing his

beam of attention until it was the only thing he perceived. After that,

he’d abruptly throw it aside and make himself forget it. He utterly

detached himself, blanking out all memory, thus achieving an exhausted

forgetfulness and charging the sigil with the energy of ‘free belief’,

thus sealing its potency.