|

Starry

Nights and Endless Miseries

Paul Newman reviews

the career of the writer Colin Wilson.

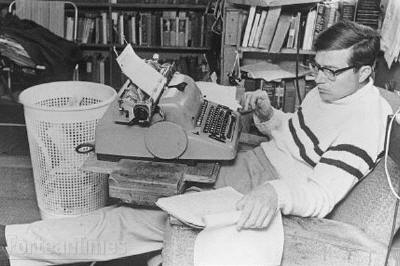

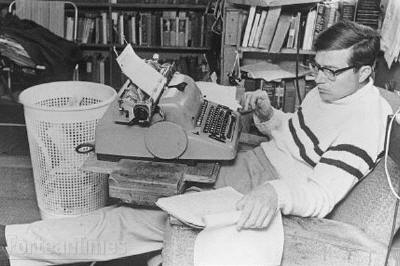

Colin Wilson is an internationally acclaimed writer

living in Cornwall. He moved to Gorran Haven in 1957 and has remained

there ever since. His memories go back to the early art colony of

Mevagissey that featured

characters

like the critic and militant pacifist Derek Savage, the artist Lionel

Miskin, the novelist Frank Baker, the poet Sidney Graham, and the

psychologist and anthropologist John Layard. characters

like the critic and militant pacifist Derek Savage, the artist Lionel

Miskin, the novelist Frank Baker, the poet Sidney Graham, and the

psychologist and anthropologist John Layard.

He favoured the Duchy because of its bracing cliff

scenery, its old-fashioned, companionable pubs and remoteness from the

bustle and gossip of London. It was a place where he could walk, think

and get down to serious work. Now, with over a hundred published books

behind him, he can be regarded as a grand old man of letters, but he is

still clear-headed, hardworking and quietly determined.

Hailed as a genius when he published his first book

The Outsider in June 1957, Colin Wilson was later pilloried and

lambasted for the follow-up work Religion and the Rebel and for a

disreputably readable oeuvre that, as the years advanced, took in pulp

fiction with philosophical overtones, critical essays, books on booze,

murder, astronomy, sexology, weird phenomena, history and ancient

wisdom, several of which are blatantly infused with ‘ideas’ about how

man may bring about personal transformation by developing the capacity

to have endless ‘peak experiences’.

The Angry Years

His last book The Angry Years was an account

of the cultural phenomenon of the Angry Young Men who dominated the

latter half of the 1950s. Often compared to America’s ‘Beat Generation’,

the Angries were more restrained and conventional; also, with the

exception of Wilson, they had little interest in Buddhism or religious

mysticism, being more interested in the persevering with the class war.

The book is unique in that it is written by one of the few surviving 'Angries'

who skilfully recreates the literary battle-zone of the period. In his

overview of his contemporaries, Colin Wilson combines an Orwellian

plainness of style with panoramic panache as he dispenses judgements

that are philosophical and personal as well as literary. Instead of

evaluating writers like John Braine, Kingsley Amis, Iris Murdoch and

Arnold Wesker by their imaginative or narrative skills, he asks of them,

“How does the attitude they embody take us forward, enlarge our

understanding of the problems with which the century presents us?” For a

start, John Osborne’s groundbreaking Look Back in Anger is found

wanting – “It was like a furious letter that someone writes to get

pent-up anger and frustration off his chest – but then usually thinks

better of sending, and throws in the fire. It was too personal, too

vindictive, too undisciplined.” Neither is Kingsley Amis’s comic

masterpiece Lucky Jim thought to be particularly rib-tickling or

the plays of Samuel Beckett especially profound.

On

the other hand, John Braine’s Room at the Top receives a

respectful salutation. So do the plays of Arnold Wesker, the novels of

Iris Murdoch and Doris Lessing. Wilson also commends Alan Sillitoe, an

outstanding novelist of working class angst and one of the finest

British short story writers of the century. His treatment is thorough,

painstaking and magisterial, convincing the reader that the AYM was not

a mid-century farce with literary overtones (as the late Humphrey

Carpenter preferred it) but a cluster of highly distinctive, vehemently

impressive talents who wrote aggressively and humorously about social

and political issues, especially that sense of class-ridden constriction

and stagnation that prevailed before the ‘wind of change’ blasted

through society and ruffled hairstyles and reputations. On

the other hand, John Braine’s Room at the Top receives a

respectful salutation. So do the plays of Arnold Wesker, the novels of

Iris Murdoch and Doris Lessing. Wilson also commends Alan Sillitoe, an

outstanding novelist of working class angst and one of the finest

British short story writers of the century. His treatment is thorough,

painstaking and magisterial, convincing the reader that the AYM was not

a mid-century farce with literary overtones (as the late Humphrey

Carpenter preferred it) but a cluster of highly distinctive, vehemently

impressive talents who wrote aggressively and humorously about social

and political issues, especially that sense of class-ridden constriction

and stagnation that prevailed before the ‘wind of change’ blasted

through society and ruffled hairstyles and reputations.

In order to produce this book, a great deal of hard

reading was required, shadowing the careers of many of the forgotten

figures into terminal decline, commenting intelligently on their later

works and not just the titles that grabbed the headlines. (Never before

have I met anyone prepared to discuss the later novels of, say, John

Wain.) As Colin Wilson appraises these writers from his own special

‘existential’ viewpoint, he rules rather harshly on Sam Beckett, “a

writer who poisons our cultural reservoirs”, but is appreciative, say,

of the later political plays of Arnold Wesker.

For his research, obviously Colin Wilson ransacked

not only his memory and journals of the period, but many standard

biographies and sources, finally producing a commentary that was far

livelier and more gripping than most cultural studies, yet nearly all

the critics received it in a dazed, deadpan, lacklustre fashion, as if

it

were

a deadly boring work about deadly boring people. One got the impression

the reviewers had not bothered to read the writers whose works were

summarised and were therefore unable to dispute or agree with what was

expressed. However, despite an overall ignorance, they had nevertheless

acquired the attitude of writing about Wilson in a mildly derogatory

fashion. Obviously, if the book had been that bad, Robson Books

would not have accepted it, for most publishers are aware that cultural

studies are not that easy to sell. Although it had done its job

in a lively, provocative and approachable way, diligently setting out

the facts and combining them with personal insight, not a single critic,

with the possible exception of Gary Lachman in The Independent,

was alert or polite enough to acknowledge that point. Not one of them

applauded Wilson for delivering readable goods and providing information

not elsewhere available. How does one account for this stagnant critical

reaction, utterly at odds with Wilson’s enthusiastic fan base, many of

whom proclaim him as a genius, as he once hinted himself, much to his

regret (thus inheriting a journalistic legacy of catcalls, jeers and

cartoons). How much is Wilson responsible for this inability of others

to listen or comprehend his basic message? were

a deadly boring work about deadly boring people. One got the impression

the reviewers had not bothered to read the writers whose works were

summarised and were therefore unable to dispute or agree with what was

expressed. However, despite an overall ignorance, they had nevertheless

acquired the attitude of writing about Wilson in a mildly derogatory

fashion. Obviously, if the book had been that bad, Robson Books

would not have accepted it, for most publishers are aware that cultural

studies are not that easy to sell. Although it had done its job

in a lively, provocative and approachable way, diligently setting out

the facts and combining them with personal insight, not a single critic,

with the possible exception of Gary Lachman in The Independent,

was alert or polite enough to acknowledge that point. Not one of them

applauded Wilson for delivering readable goods and providing information

not elsewhere available. How does one account for this stagnant critical

reaction, utterly at odds with Wilson’s enthusiastic fan base, many of

whom proclaim him as a genius, as he once hinted himself, much to his

regret (thus inheriting a journalistic legacy of catcalls, jeers and

cartoons). How much is Wilson responsible for this inability of others

to listen or comprehend his basic message?

Early Biography

First let us set the basic biographical record

straight. Colin Henry Wilson was born in Leicester in 1931 and received

most of his formal education at the local Gateway secondary school.

Afterwards he took jobs as a laboratory assistant at the Gateway and

later as an office worker in the city. In his autobiography Voyage to

a Beginning, he recalled working for the Collector of Taxes. His

boss was a jolly sympathetic gentleman named Mr Sidford and he

remembered the other employees: Joyce, “a highly attractive young

married woman who wore expensive clothes and obviously longed for the

Riviera”; Desmond, “a handsome, smart and highly efficient young man in

rimless glasses, who looked like Ian Fleming’s James Bond but actually

seemed to lead a blameless life”; Ken, “who was about to marry, and

often talked to me at length about the joys of married life”; Millicent,

“an attractive short-sighted Jewish girl with a sensual mouth and a

contralto voice” with whom Colin Wilson was to become romantically

involved. There is little point in adding further details – one can only

recommend readers to acquire this entertaining autobiography or its less

intense if more broadly informative update Dreaming To Some Purpose.

Both books capture well the flavour of the times as well as providing a

fund of anecdotes, hilarious, provocative and intriguing.

Although his employers were more sympathetic to a

deeply introspective young intellectual masquerading as an average

trainee than they would be in these ruthless times, Wilson found it

difficult to settle into an orderly rhythm. Eventually he jacked in the

clerical job and began looking around for other outlets – all the time

reading intensely and evolving his philosophy.

The New Lost

During an interlude, he joined the RAF, but found the

routines of service life stifling. When his discontent became

unbearable, he feigned homosexuality in order to gain a discharge. Once

again a citizen of the world, he met and married his first wife, Betty,

produced a son, Roderick, and wandered on the Continent, eventually

settling back in London. Owing to a paucity of suitable accommodation

and money problems, his marriage faltered and he continued to work as a

washer-up in sundry coffee bars and, during his spare time, drafted the

outline of The Outsider (1956). This turned out to be one of the

major titles of the decade, a seminal work influencing the reading

matter and outlook of a generation. Containing arresting profiles of men

like

Van Gogh, Vaslav Nijinsky, T.E. Lawrence, Herman Hesse and Frederick

Nietzsche, it explored their isolation and revolt in an urgent,

arresting way. Even their neuroses was presented as vital and exciting,

a necessary distress rather than a dreary encumbrance. Only by feeling

‘outside’ society, Wilson argued, could such men have gained insight

into its ailments and thereby propose a route of healing. like

Van Gogh, Vaslav Nijinsky, T.E. Lawrence, Herman Hesse and Frederick

Nietzsche, it explored their isolation and revolt in an urgent,

arresting way. Even their neuroses was presented as vital and exciting,

a necessary distress rather than a dreary encumbrance. Only by feeling

‘outside’ society, Wilson argued, could such men have gained insight

into its ailments and thereby propose a route of healing.

Equally significantly, The Outsider

pin-pointed a new underclass of more-than-averagely intelligent young

men and women, too restless and imaginative to settle for conventional

jobs, yet not integrated and disciplined enough to make it as

free-standing writers or artists. These, disparagingly called the “new

lost”, are best epitomised – or satirised – by the vehemence of Jimmy

Porter, the hero of John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger, who

vented his spleen on every available target. Although classed as one of

the ‘Angry Young Men’, along with John Osborne, Kingsley Amis and John

Wain, Wilson spurned both the label and Osborne’s play. He thought

Porter’s rantings should be the start of a long educative process and

not an interminable circulatory exercise like swallowing one’s tail.

James Dean of Literature

The Outsider found a

prestigious, brilliant publisher in Victor Gollancz, who employed

marketing techniques that exaggerated the popularity of his titles,

thereby encouraging buyers. The Outsider fielded glowing reviews

in the Sunday Times and The Observer, with the result that

Colin Wilson achieved instant fame. He woke one morning like Lord Byron

to find cultural London whispering his name. The time was right. For

years people had been asking: Where was the postwar generation of

British artists and intellectuals? With the accompanying appearances of

John Osborne’s emotionally harrowing Look Back in Anger and

Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, an enjoyable, iconoclastic novel of

university life, it seemed they had officially arrived. Within a few

months, the phrase Angry Young Man was on everyone’s lips and Wilson,

with his forthright views, was fixed as one of their ringleaders. At the

same time, in America, the Beats – deriving from ‘beatitude’ or

spiritual illumination – were pursuing paths of crazy wisdom. Jack

Kerouac, Neal Cassady, William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg and their

entourage were travelling restlessly from state to state, listening to

jazz, drinking, smoking marijuana or stealing cars.

Prior

to publication, Wilson had been sleeping on Hampstead Heath in order to

save money and secure time in which to write and study. This anecdote

made perfect fodder for the British press, and the young intellectual

was subject to a rapid makeover. One morning he was a nonentity; the

next photographers were perpetuating images of him enshrouded in his

sleeping bag reading Nietzsche or Shaw or even Wilson. Highbrow critics

knelt in obeisance before his “luminous intelligence” and every variety

of human being - from milkmen to solicitors – pounced on him exclaiming,

“Mr Wilson, I believe I’m an Outsider!” Prior

to publication, Wilson had been sleeping on Hampstead Heath in order to

save money and secure time in which to write and study. This anecdote

made perfect fodder for the British press, and the young intellectual

was subject to a rapid makeover. One morning he was a nonentity; the

next photographers were perpetuating images of him enshrouded in his

sleeping bag reading Nietzsche or Shaw or even Wilson. Highbrow critics

knelt in obeisance before his “luminous intelligence” and every variety

of human being - from milkmen to solicitors – pounced on him exclaiming,

“Mr Wilson, I believe I’m an Outsider!”

Looking back on the fifties, a correspondent to an

arts magazine summarised the atmosphere. “I remember,” wrote Louis

Sterton, “spending a good part of my youth drinking coffee and chatting

with fellow ‘intellectuals’ about existentialism, the beat generation,

etc. ad nauseam. Wilson was a kind of young intellectuals’ icon, a James

Dean of the book world, who seemed both rebellious and individualistic,

a bloke who was determined to do things his way. Of course we understood

hardly anything he wrote – I’m afraid The Outsider lost me inside

the first fifty pages - but we were all happy to say, ‘Good on yer mate’

when he got up the Establishment’s nose.”

Oscar Wilde remarked style is more important than

sincerity – an aphorism borne out in the press’s early treatment of

Wilson. They mangled and mocked the metaphysics and concentrated on the

image to which they could attach stories. Wilson provided them with the

right type of bait. Tall, confident, romantically scruffy and

effortlessly eloquent, his views were sought on subjects as varied as

women's fashion, space satellites, CND and socialism. At one point in

his career, he was even asked to write an introduction to a gardener’s

yearbook. “But I hate gardening,” he protested. “That’s fine,” the

editor responded. “Just tell us how you hate it.” So Wilson went ahead

and wrote the essay – a lively denunciatory piece that still reads well.

Sex

and Metaphysics Sex

and Metaphysics

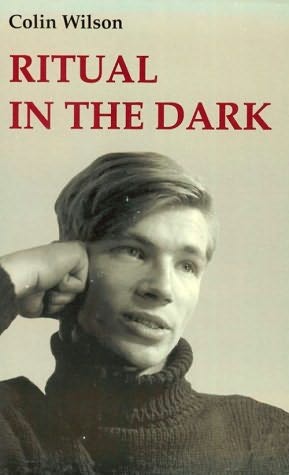

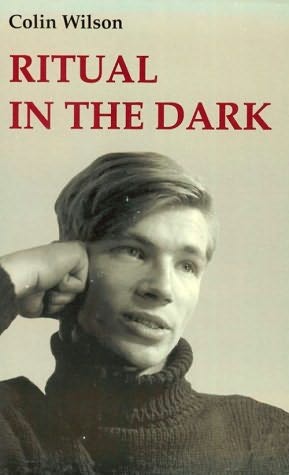

Wilson backed up criticism with novels. His first

Ritual in the Dark (1959) dealt with a series of Jack the Ripper

type killings in London. It was in some ways a gaunt, jokeless tract,

heavily overcast in tone, but irradiated by a prowling energy. There was

plenty of violence, plenty of sex, plenty of philosophy, and the odd

thing was that all three areas were blended. If the central character,

Gerard Sorme, caught sight of the edge of a girl’s slip, a lengthy

disquisition might follow on what was taking place in the hero’s body

and soul. I imagine that many of its male readers were entranced to

learn that ogling was a major branch of philosophy and from then on

would pace the streets, ball-eyed, eager to drink in all the metaphysics

on display.

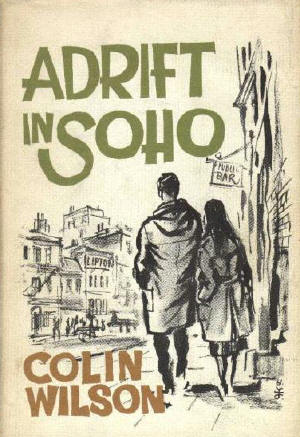

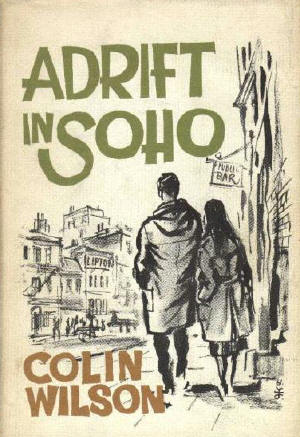

Savagely attacked in several papers, Ritual

received an accolade by Dame Edith Sitwell writing in The Sunday

Times and was followed by Adrift in Soho (1961), a picaresque

story of a young writer from the provinces seeking refuge in the

companionable squalor of bedsit London. The Kerouac-like charm of the

narrative takes in a varied cast of dropouts, actors, sex-crazed

painters, soulful poets and weasel-nosed landladies - “so good is Mr

Wilson's prose you can see and smell it all”, The Times Literary

Supplement enthused.

In Ritual and two other of his novels Wilson

used as an alter ego a man named Gerard Sorme who is best characterised

as a freelancing intellectual with a penchant for wine, whisky and

copulation. Sorme made his debut in Ritual as an owlishly serious

young man who was constantly taking off and putting on his cycle clips

before and after seducing some lapsed Jehovah's witness or pretty

student nurse. As he progressed through a cycle of novels, Sorme became

more financially secure, shedding his cycle clips for a saloon car, but

somehow less human than that dank fifties figure shivering as he holds a

dripping raincoat over a paraffin stove in some barren bedsit. “Poor

Gerard Sorme,” a critic wrote of The God of the Labyrinth (1970)

– an engaging phallocentric jaunt amid the rakes of the 18th century –

“nothing between the library list in his head and that vital organ down

there.”

Leakage of Energy

Despite

these lighter moments, Wilson was regarded as a ‘serious’ – indeed

passionately earnest – young writer, an existentialist who sought to

promote a religious attitude. Not like Kierkegaard, say, who was a

Christian, but more like Shelley who sensed and reverenced a principle

behind creation larger than anything an individual might divine. The

vastness of the cosmos and the multiplicity of its created forms became

a source of vexation to Kierkegaard, creating fear and trembling. This

abyss of potentialities, this dizzying maze of meaning, was similar to

what Sartre’s nausea at life’s steaming multiplicity. But Wilson denied

the validity of such responses. Why be forced into a leap of faith or be

overcome with disgust merely because one is faced with infinite variety?

These are superficial responses, he argued. If you look at all these

living forms and choices with the right set of intentions, they become

merely tools and agents of your inner certainty or sense of purpose.

They have the power to trigger elation as well as doubt. So, in a sense,

while using an existential scaffold, Wilson reached a different

conclusion. He saw life as a bed of hope and inspiration while Sartre

viewed it as a hard-faced taskmaster. Despite

these lighter moments, Wilson was regarded as a ‘serious’ – indeed

passionately earnest – young writer, an existentialist who sought to

promote a religious attitude. Not like Kierkegaard, say, who was a

Christian, but more like Shelley who sensed and reverenced a principle

behind creation larger than anything an individual might divine. The

vastness of the cosmos and the multiplicity of its created forms became

a source of vexation to Kierkegaard, creating fear and trembling. This

abyss of potentialities, this dizzying maze of meaning, was similar to

what Sartre’s nausea at life’s steaming multiplicity. But Wilson denied

the validity of such responses. Why be forced into a leap of faith or be

overcome with disgust merely because one is faced with infinite variety?

These are superficial responses, he argued. If you look at all these

living forms and choices with the right set of intentions, they become

merely tools and agents of your inner certainty or sense of purpose.

They have the power to trigger elation as well as doubt. So, in a sense,

while using an existential scaffold, Wilson reached a different

conclusion. He saw life as a bed of hope and inspiration while Sartre

viewed it as a hard-faced taskmaster.

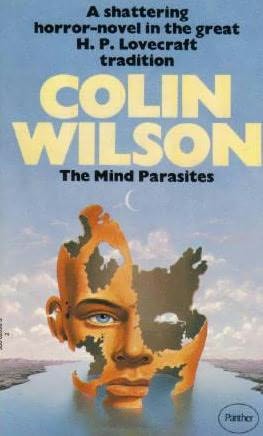

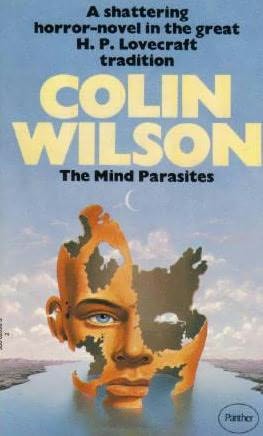

Above all, the problem of life-failure or the

inability of the human mind to sustain hope and enthusiasm obsessed him

. Deploring the manner in which men and women of genius (Keats, Byron,

Shelley) had blazed trails of glory and later succumbed to self-doubt or

suicide, he wrote The Mind Parasites (below left), an eloquent

sci-fi parable in which this process is demonised as an alien

infiltrator. If only this debilitating tendency could be overcome,

mankind might take the next step forward. Styling himself as a hedgehog

- a thinker motivated by a single big idea - Wilson restated this theme

in essay and fiction. He regarded the human will as fundamentally at

fault, too prone to depression and self-doubt:

Van Gogh painted

‘The Starry Night’, which seems to be a pure affirmation of life; but he

committed suicide, and left behind a note that said, “Misery will never

end.” According to Ayer [Freddy Ayer, the logical positivist

philosopher], this merely amounted to the expression of two different

moods, and it was as meaningless to ask which was “truer” as to ask

whether a rainy day is truer than a sunny day. My own feeling was that

the question was not only significant, but - literally - a matter of

life and death.

Essay on the New

Existentialism (1986)

An answer to this dilemma was found in the latent

power of the will or the transformative ability of the mind to convert

plummeting ‘lows’ to surging ‘highs’. If we cannot alter the weather by

our thoughts, we can at least try to change the climate of our thinking.

In such a context, the “peak experience” offered an important lead, a

euphoric state first chronicled by the psychologist Abraham Maslow.

Instead of trying to find out what made sick people sick, Maslow decided

to investigate what made healthy people healthy. His answer was that

‘self-achievers’ are regularly topped up by the “peak experience”, a

surge of unity and joy at being here. It is this ability of the

mind to energise itself – to re-fuel itself on distant horizons and

limitless possibilities – which is the key to overcoming depressed and

defeated states. Wilson criticised thinkers like Jean Paul Sartre for

underrating such moments of vision and putting undue emphasis on

contingency or the “absurdity” of the human situation.

Poisoning

the Cultural Wells Poisoning

the Cultural Wells

So far, so good, but Wilson covers a great deal of

ground swiftly. There are times when he almost goes so far as creating

his own enemies, whether they are aware of it or not. For instance, the

writer Samuel Beckett is accused of poisoning the cultural wells by dint

of his pessimistic, downbeat writings, thereby equivalently inflating

the import of Wilson’s attack. To him Beckett’s vision of life is too

dreary and distorted to be pertinent to anyone but Beckett.

Similarly the opinions of Jean Paul Sartre, to whom

Wilson’s personal philosophy is partly indebted, tends to receive a

coolish appraisal. Academically speaking, Wilson’s system might be

called an Anglo-Saxon offshoot of Sartre’s existentialism that just

draws short of mysticism. The precise point of its origin or ‘breakaway’

is Sartre’s reaction to the physical world or what he calls ‘nausea’, a

kind of sickness brought on by the unrelenting assault of sensual and

visual information that life on earth supplies. Roquentin, a character

in Sartre’s novel Nausea, is shown to be overwhelmed and revolted

by things like the many roots of a tree, “a knotty mass, entirely

beastly…”

Wilson, rightly, points out that this is partial

rather than clear thinking. Surfaces that meet the eye are neither one

thing nor another, not intrinsically revolting, pleasing or absurd.

Wilson does not incorporate revulsion at surface appearances or politics

in his philosophical manifesto, arguing that once people achieve mental

health or repeated ‘peak experiences’, they are able to realise their

potential and live in a reality of heightened values, meaning and

sensation. Their life will take the right turn and, hopefully,

responsible political decisions will emerge as a natural outcome. This

is certainly an optimistic statement that has attracted a

following as well as scepticism.

Propagandists for Existence

Wilson

can appear too prescriptive about a writer’s negativity or lack of

optimism. For, in a sense, writers and artists are almost doomed to be

propagandists for existence, however much they squirm, protest, deny or

descry it. Each time they put a word to paper they are affirming their

participation in the drama of ‘being here’ and, if they choose to

describe suffering, they are still singling out and privileging their

perception of it. Wilson maintains there is too much trivia and

pessimism around, particularly in literary culture, holding us back from

solving vitally important issues. But this is a debatable proposition.

It could be equally argued that it is man’s irrepressible, foolish

optimism that is the culprit, the notion that however many wars he wages

or devastations he wreaks, always a victor will spring up at the end to

take things forward or backward. Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini were all

optimists, assuming they would quash resistance and never get their

comeuppance. A blind, tunnel-visioned optimism is responsible for the

destruction of the rain forest and nearly every other major ecological

problem. Wilson

can appear too prescriptive about a writer’s negativity or lack of

optimism. For, in a sense, writers and artists are almost doomed to be

propagandists for existence, however much they squirm, protest, deny or

descry it. Each time they put a word to paper they are affirming their

participation in the drama of ‘being here’ and, if they choose to

describe suffering, they are still singling out and privileging their

perception of it. Wilson maintains there is too much trivia and

pessimism around, particularly in literary culture, holding us back from

solving vitally important issues. But this is a debatable proposition.

It could be equally argued that it is man’s irrepressible, foolish

optimism that is the culprit, the notion that however many wars he wages

or devastations he wreaks, always a victor will spring up at the end to

take things forward or backward. Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini were all

optimists, assuming they would quash resistance and never get their

comeuppance. A blind, tunnel-visioned optimism is responsible for the

destruction of the rain forest and nearly every other major ecological

problem.

There is also a problem about the ‘peak experience’.

Is it explicitly ethical and improving? Do these ‘peak experiences’

motivate monsters and tyrants as well as healthy men? In several of his

books, Wilson talks about the intensity that murderers seek, the need to

release themselves through an act of violence, and suggests an

equivalence in the sexual orgasm. Doesn’t this sound dangerously near a

peak experience? His reply to this, I imagine, would run along these

lines. The peak experience is neither moral nor amoral. It is simply a

bedrock vision of how things actually are beyond the veil of

habit, desensitisation and dumb acceptance many of us acquire over the

years. Someone whose character was inherently warped or corrupted would

be unable to grasp this truth in a purely objective way simply because

his personal urges would tend to distort things.

Seeing

Beyond Seeing

Beyond

Although I raise various issues and problems of

definition, they do not add up to an adequate reason to reject Wilson’s

basic outlook and philosophy which is healthy, restorative and gripping

on a purely investigative level, in that he draws the whole history of

philosophy into it. In the same essay in which he refers to Van Gogh’s

misery and suicide, he promotes the role of vision – of seeing beyond

the problems that afflict everyday life and rejects the levelling notion

that all humanity must be viewed in the same light. In particular, he

recalled a conversation with the French intellectual, Albert Camus.

Praising the latter’s work, he suggested that it contained the germ of

an optimistic existentialism. Shaking his head, Camus pointed to a

Parisian teddy boy slouching past in the street. “What is good for him

must be good for me also,” he told Wilson.

“I got very excited and said that was preposterous. I

could see, of course, what he meant: that his starting point had to be

the same “triviality of everydayness” (Heidegger's phrase) that

confronted the teddy boy when he opened his eyes in the morning. But

Camus was saying that he was unable to see beyond that triviality. And

it is a philosopher’s job to see beyond. All revolutions in thought

begin with an attempt to “see beyond”. What if Einstein had decided that

he could not publish his theory of relativity because a Parisian teddy

boy would find it incomprehensible?”

In other words, it is the duty of men and women to

rise to the challenge presented by people like Einstein – by making an

effort at understanding – rather than negate their contributions. The

idea that, if you cannot be heard by everybody, you might as well talk

to nobody, is hardly applicable to Camus, who was born to a poor,

practically bookless family in Algeria. All his innate ability would

have been wasted without the persistence and determination inspired by

his own self-belief. You have to convince yourself before you have half

a chance of convincing others.

I have dealt at length with the early years and

The Outsider because they hold the key to Colin Wilson’s subsequent

development. But I am aware that many people have become acquainted with

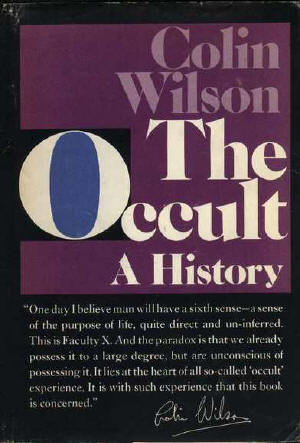

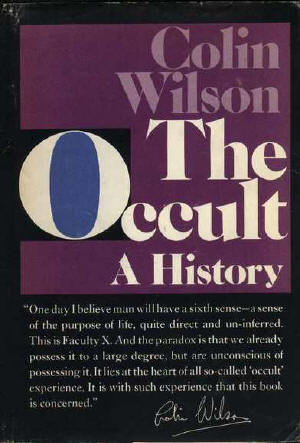

him through books like The Occult (1971) or compendious tomes on

murder and mysterious happenings or through his articles in the Daily

Mail or occasional television appearances with personalities like

Yuri Geller. At this very moment, for instance, they might be reading

Alien Dawn, a readable and profound analysis of the historical

backdrop and implications of all those reports of UFOs and abductees, or

one of his many short lucid expositions on spiritual teachers like Carl

Jung, Rudolf Steiner, George Gurdjieff and P.D.

Ouspensky.

How do these many strands connect? What is their

crowning knot?

Wilson’s reply might run along these lines. Outsiders

have often been rescued from misery and oppression by

moments

of deep insight and near-drunken joy. Mystics and occultists also seek

this feeling of breadth and expansion. Even magic is a kind of ‘imaging’

or concentrating and deepening one’s mental powers. Phenomena like UFOs

force dramatic changes in those who see them; they are never quite the

same again, for they have glimpsed the potential of other worlds, other

modes of being. Murderers, too, crave expansion and release, but their

methods are crude and brutal. Repeated acts of violence release opiates

in the brain but the effect wears off, leaving them trapped in the coils

of their viciousness. moments

of deep insight and near-drunken joy. Mystics and occultists also seek

this feeling of breadth and expansion. Even magic is a kind of ‘imaging’

or concentrating and deepening one’s mental powers. Phenomena like UFOs

force dramatic changes in those who see them; they are never quite the

same again, for they have glimpsed the potential of other worlds, other

modes of being. Murderers, too, crave expansion and release, but their

methods are crude and brutal. Repeated acts of violence release opiates

in the brain but the effect wears off, leaving them trapped in the coils

of their viciousness.

So Wilson is saying, despite different paths, the

goal is identical. Men and women, in order to fulfil the destiny

implicit in being here, seek new intensities of being. They long

to open the door in the wall, the window in the mind, the gate that

leads to the farthermost shore. They want their lives to stay

permanently open to spiritual and physical possibilities. In a sense he

is a modern religious visionary, seeking to draw heaven down to earth

and to re-unite sensation and spirit. But this is a highfalutin way of

describing a philosophy that is pre-eminently practical, a method of

grasping and configuring the reality with which each of us is

confronted.

Japan’s Literary Idol

To return to the original question, posited and left

unanswered at the outset of this article, if Wilson has so much to

offer, why are his books routinely reviewed in a perfunctory way and his

ideas dismissed or passed over lightly?

Many

critics thinks it is because he writes too much, an almost irritating

variety, and that so many of his books are potboilers, crime

compendiums, books on serial killers and ancient wisdom and the

occasional sci-fi fantasy. But a secondary reason is that he has no

fixed literary niche. Many

critics thinks it is because he writes too much, an almost irritating

variety, and that so many of his books are potboilers, crime

compendiums, books on serial killers and ancient wisdom and the

occasional sci-fi fantasy. But a secondary reason is that he has no

fixed literary niche.

Wilson’s first book, The Outsider, advanced an

argument that combined philosophy, psychological theories, social and

literary criticism. It appeared to be urging on a spiritual or cultural

renaissance, a creative evolutionism, and was developed through a cycle

of works, loosely linked in theme and picking up new insights en route.

But he realised the audience for these works was select and (relatively)

highbrow. Hence, side by side, he developed a more popular line, turning

out crime novels and novels of ideas that incorporated similar

consciousness-raising ideas to his non-fiction. In each book, he tended

to slip in a bit of personal philosophy. If Wilson had been a popular

religious writer of the 19th century, this might have proven

an extraordinarily effective technique, but as this is very much an age

of specialisation, such a versatile, piecemeal approach does not build

up the solid readership of, say, a popular thriller writer who delivers

a consistent commercial package.

There was a brief period when he almost slipped below

the horizon of public recognition, not for long though, producing the

massive The Occult (1971) which rekindled the spotlights and

received rapturous reviews from highbrow and lowbrow alike and sustained

publicity for several years. So, although Wilson is an internationally

acknowledged author, the most-read English writer in Japan (“In England,

Mr Wilson,” began a Japanese interviewer, “you must be as famous as

Charles Dickens?”), he still occupies an odd, overlooked position in

Britain as the last of the Angry Young Men who has slightly cranky ideas

and a conviction about his own genius.

In

a sense, the marketing factors that held him back have become strengths

in that by now he has acquired enough zealous readers to buy a book on

any topic he handles, believing they are vital links in the author’s

unique chain of creation. Furthermore, however much he’s criticised,

each year he throws a new title into the face of his detractors. His

latest, in fact, written in collaboration with Don Hotson, is called

Will Shakespeare’s Hand and boldly goes where no existentialist has

gone before, for it penetrates the sacred academic grove of William

Shakespeare, being a provocative new interpretation of his life and its

relation to the plays and sonnets. If this is not met with approval by

the critics, no doubt Wilson will cheerfully weather the storm and

supply another title by next year. This process will carry on even after

they come up with the goods and assess in fair, responsible fashion the

spectacular oeuvre of a fascinating, historically important author. In

a sense, the marketing factors that held him back have become strengths

in that by now he has acquired enough zealous readers to buy a book on

any topic he handles, believing they are vital links in the author’s

unique chain of creation. Furthermore, however much he’s criticised,

each year he throws a new title into the face of his detractors. His

latest, in fact, written in collaboration with Don Hotson, is called

Will Shakespeare’s Hand and boldly goes where no existentialist has

gone before, for it penetrates the sacred academic grove of William

Shakespeare, being a provocative new interpretation of his life and its

relation to the plays and sonnets. If this is not met with approval by

the critics, no doubt Wilson will cheerfully weather the storm and

supply another title by next year. This process will carry on even after

they come up with the goods and assess in fair, responsible fashion the

spectacular oeuvre of a fascinating, historically important author.

Paul Newman is editor of

'Abraxas Unbound',

and author of

'The Tregerthen Horror' and 'Aleister

Crowley and the Cult of Pan'

|

On

the other hand, John Braine’s Room at the Top receives a

respectful salutation. So do the plays of Arnold Wesker, the novels of

Iris Murdoch and Doris Lessing. Wilson also commends Alan Sillitoe, an

outstanding novelist of working class angst and one of the finest

British short story writers of the century. His treatment is thorough,

painstaking and magisterial, convincing the reader that the AYM was not

a mid-century farce with literary overtones (as the late Humphrey

Carpenter preferred it) but a cluster of highly distinctive, vehemently

impressive talents who wrote aggressively and humorously about social

and political issues, especially that sense of class-ridden constriction

and stagnation that prevailed before the ‘wind of change’ blasted

through society and ruffled hairstyles and reputations.

On

the other hand, John Braine’s Room at the Top receives a

respectful salutation. So do the plays of Arnold Wesker, the novels of

Iris Murdoch and Doris Lessing. Wilson also commends Alan Sillitoe, an

outstanding novelist of working class angst and one of the finest

British short story writers of the century. His treatment is thorough,

painstaking and magisterial, convincing the reader that the AYM was not

a mid-century farce with literary overtones (as the late Humphrey

Carpenter preferred it) but a cluster of highly distinctive, vehemently

impressive talents who wrote aggressively and humorously about social

and political issues, especially that sense of class-ridden constriction

and stagnation that prevailed before the ‘wind of change’ blasted

through society and ruffled hairstyles and reputations.

Prior

to publication, Wilson had been sleeping on Hampstead Heath in order to

save money and secure time in which to write and study. This anecdote

made perfect fodder for the British press, and the young intellectual

was subject to a rapid makeover. One morning he was a nonentity; the

next photographers were perpetuating images of him enshrouded in his

sleeping bag reading Nietzsche or Shaw or even Wilson. Highbrow critics

knelt in obeisance before his “luminous intelligence” and every variety

of human being - from milkmen to solicitors – pounced on him exclaiming,

“Mr Wilson, I believe I’m an Outsider!”

Prior

to publication, Wilson had been sleeping on Hampstead Heath in order to

save money and secure time in which to write and study. This anecdote

made perfect fodder for the British press, and the young intellectual

was subject to a rapid makeover. One morning he was a nonentity; the

next photographers were perpetuating images of him enshrouded in his

sleeping bag reading Nietzsche or Shaw or even Wilson. Highbrow critics

knelt in obeisance before his “luminous intelligence” and every variety

of human being - from milkmen to solicitors – pounced on him exclaiming,

“Mr Wilson, I believe I’m an Outsider!”

moments

of deep insight and near-drunken joy. Mystics and occultists also seek

this feeling of breadth and expansion. Even magic is a kind of ‘imaging’

or concentrating and deepening one’s mental powers. Phenomena like UFOs

force dramatic changes in those who see them; they are never quite the

same again, for they have glimpsed the potential of other worlds, other

modes of being. Murderers, too, crave expansion and release, but their

methods are crude and brutal. Repeated acts of violence release opiates

in the brain but the effect wears off, leaving them trapped in the coils

of their viciousness.

moments

of deep insight and near-drunken joy. Mystics and occultists also seek

this feeling of breadth and expansion. Even magic is a kind of ‘imaging’

or concentrating and deepening one’s mental powers. Phenomena like UFOs

force dramatic changes in those who see them; they are never quite the

same again, for they have glimpsed the potential of other worlds, other

modes of being. Murderers, too, crave expansion and release, but their

methods are crude and brutal. Repeated acts of violence release opiates

in the brain but the effect wears off, leaving them trapped in the coils

of their viciousness.

In

a sense, the marketing factors that held him back have become strengths

in that by now he has acquired enough zealous readers to buy a book on

any topic he handles, believing they are vital links in the author’s

unique chain of creation. Furthermore, however much he’s criticised,

each year he throws a new title into the face of his detractors. His

latest, in fact, written in collaboration with Don Hotson, is called

Will Shakespeare’s Hand and boldly goes where no existentialist has

gone before, for it penetrates the sacred academic grove of William

Shakespeare, being a provocative new interpretation of his life and its

relation to the plays and sonnets. If this is not met with approval by

the critics, no doubt Wilson will cheerfully weather the storm and

supply another title by next year. This process will carry on even after

they come up with the goods and assess in fair, responsible fashion the

spectacular oeuvre of a fascinating, historically important author.

In

a sense, the marketing factors that held him back have become strengths

in that by now he has acquired enough zealous readers to buy a book on

any topic he handles, believing they are vital links in the author’s

unique chain of creation. Furthermore, however much he’s criticised,

each year he throws a new title into the face of his detractors. His

latest, in fact, written in collaboration with Don Hotson, is called

Will Shakespeare’s Hand and boldly goes where no existentialist has

gone before, for it penetrates the sacred academic grove of William

Shakespeare, being a provocative new interpretation of his life and its

relation to the plays and sonnets. If this is not met with approval by

the critics, no doubt Wilson will cheerfully weather the storm and

supply another title by next year. This process will carry on even after

they come up with the goods and assess in fair, responsible fashion the

spectacular oeuvre of a fascinating, historically important author.