|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Art in Wales: Politics of Engagement or Engagement with Politics? Artist and writer Iwan Bala describes a strand of post-war politically engaged art from Wales, with particular reference to the flooding of the village of Capel Celyn in the early 1960s.

To embrace environmental issues, feminist issues, ethnicity, cultural identity - these are essential post-Modern tropes. The choice to be an artist was at one time a political stance, but like much else today it seems demoted to a ‘lifestyle’ choice, and an increasingly popular one. Art now is a much more varied and complex area of production compared to what it was half a century ago. In the 1970’s the Beca collective of artists was a somewhat unheralded presence in the art of Wales. Some exhibitions were cancelled due to the ‘political’ nature of their work in the 1980’s, yet today the late Paul Davies who, with his brother Peter, established Beca, is widely recognised as a radical force in Welsh Art.[iii] Beca, which included Ivor Davies and later Tim Davies (Welsh Lady: photo below left), film-maker Peter Telfer and myself, could be said to have grown out of the 1960’s art scenes of London and Paris (Ivor Davies was particularly involved in the ‘Destruction in Art’ movement of the early and mid sixties) as much as, if not more than, by its base in Wales. But the base in Wales was itself a highly politicised one, following the drowning of Capel Celyn village in order to create a reservoir for the city of Liverpool. The activities of the Welsh Language Society in response to Saunders Lewis’s ‘Tynged yr Iaith’ (the Fate of the Language) address, warning that the language was reaching a point of no return, were also hugely formative for my generation. In the book of essays, ‘Certain Welsh Artists’ which I compiled in 1999, I describe a ‘custodial aesthetics’ in the work of several artists in Wales, artists who one way or another promote a notion of Welsh identity in their work. Much of this notion of ‘custodianship’ comes from the realisation that as a people (Welsh speakers in particular) we are burdened with the responsibility of keeping memory, heritage and identity alive.

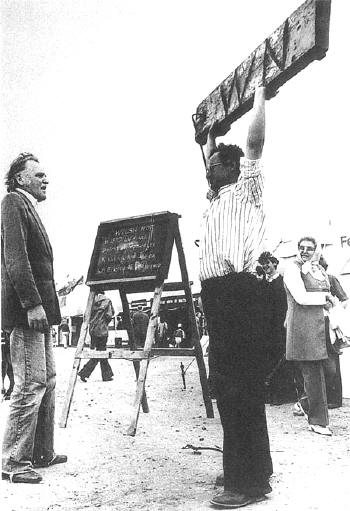

The ‘performance’ aspects

of Paul Davies’ work, notably the holding up above his head, of a railway

sleeper with WN (Welsh Not) written on it, at The National Eisteddfod of Wrexham

in 1977 (picture above right), bore similarities to Cymdeithas yr Iaith’s

dumping of English only road signs on the steps of the Welsh Office.

Throughout the late 70’s and the 1980’s, this artistic politicization was occurring, and cultural arguments about the language and about devolution were widespread in Wales. Not long afterwards of course, socialist militancy breathed its last gasp defending the miners during the strike of 1985. Those artists who were the daughters and sons of miners, often retain their politicized stance. I recall a group of us in Cardiff organised art auctions to support the miners. There was a list of ‘just’ causes; sympathies lay with the Republican side in Northern Ireland; our ‘nationalism’ was (like theirs we felt) not a narrow one. It was socialist, republican and international in its scope. It supported minorities under threat worldwide. These sensibilities, unfashionably “nationalistic” or fashionably “culturally specific” (the politics of place) are still in evidence amongst that generation. The Beca members continue as individuals to wander occasionally down that path of protest, as do others who might well be Beca members in spirit; David Garner, a miner’s son, at once springs to mind, and Carwyn Evans, (a Welsh speaker from rural west Wales) but also others, less obviously so. It has become more acceptable to dabble in ‘issues’ in this post-Modern climate, and artists who do so, particularly those coming from the ‘minorities’, have gained international reputations. These artists, like many in Wales find that their ‘formation’ has enabled them to view the world from a marginalised perspective.

As Purchaser for CASW in 2003 I acquired his last drawing, the diagrammatic “Mappa Mundi” (1993) for the collection, and it is now housed at the National Museum, Cardiff. Other artists have since come to Wales from politicised background ‘formations’. Both André Stitt and Paul Seawright are originally from Northern Ireland, and their early works were direct responses to the unavoidable political reality of Ulster. Performance artist Stitt is internationally known for his Akshuns, and with “Dwr” in 2005/06, has gone on to engage with that motif of Welsh political art, Tryweryn, by literally delving into the murky waters to produce a simple, yet compelling short film that reminds one of an endoscope penetrating into the entrails of the human body. Seawright too, has photographically commented on industrial decline in the South Wales Valleys (with which he represented Wales at the Venice Biennale 2003) before going on to evoke the barren and empty landscape of Iraq. Rabab Ghazoul is an Iraqi born artist, now resident in Cardiff who feels empowered to deal with her own issues of cultural identity in a place where such questions are part of the currency of discourse. In Wales she can relate to the issues of language loss and identity that she herself feels, having been exiled from Iraq from a very young age.

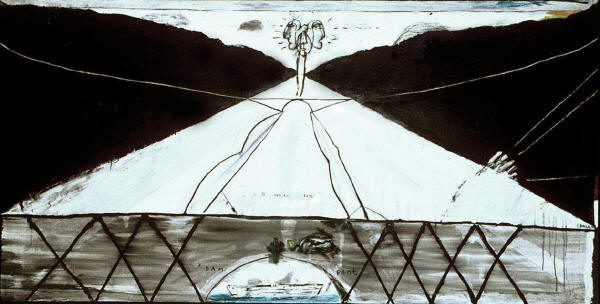

Tryweryn as a motif and metaphor has been a subject for Tim Davies, David Garner, John Meirion Morris, Marian Delyth, Ivor Davies, Aled Rhys Hughes, Carwyn Evans, Tim Page and many others. This piece of water that drowned a community, and which is still out of the control of Wales’ Assembly Government, galvanised poets, writers visual artists. My own contribution to the debate, “Dam/Pont (picture above)” is a painting in black and white that suggested that the ‘dam’ built across the river Tryweryn could also operate as a ‘bridge’ to a new future. The Tryweryn episode led circuitously to the establishing of the National Assembly for Wales, but significantly, it also had mythic resonance. The drowning of land has long been a motif of folklore in Wales, and so, this historic event echoes mythical events that form some of our ‘collective memories’. Five miles from Llyn Celyn lies Llyn Tegid, a natural lake that has just such a story attached to it. Tim Davies, born in Pembrokeshire and spiritually attached to his grandparents’ home, the once fishing village of Solfach, has a deeply felt political awareness in his work. “Black Black Walls” of 1993, first brought him to attention in Wales when it won a prize at the National Eisteddfod in Neath in 1994, but which had appeared at the East International exhibition in Norwich previously. Lumps of coal, 28,000 in all, are pierced and strung up in rows, much like bead curtains - forming a series of screens hanging from ceiling to floor. They are striking as objects in a white space, but they are also reminders of each job lost in the south Wales coal industry under Thatcher's policies. The coal is reduced "to an impotent, decorative element, like black coral threaded on string" as Dr Ann Price Owen has said[vi]. Work, or the lack of it and the loss of social cohesion that goes with unemployment, are recurring themes in Davies's work.

“Capel Celyn” won the Mostyn Open purchase prize in 1998, but before that it had been enthusiastically viewed in an exhibition also called ‘Capel Celyn’ in the Spacex Gallery in Exeter in 1997. This surprised the artist somewhat; proving that the mythic nature of the work and the historical events it alluded to (supported by accompanying text) could be well received outside Wales. This is not art that is simply “about” one country’s history, nor does it hijack history in order to create a “message”. The message is inherent and self-contained, and therefore universal. It is also minimalist in the sense that it is pared down completely to one element, and that element is repeated over and over in a labour intensive process, which the artist undertakes himself. Its politics go further, they question the supposed ‘content-less’ ideology of Minimalist art. The viewer sees a “field” of wax nails, a carpet that seems to hover in a ghostly way across the gallery floor. Beyond that, they interpret the meaning of the piece, aided by its title and the statement made to go with it. In the catalogue essay for Spacex, curator Alex Farquharson writes; “Art on the margins, can still act for the community in place of absent governmental or media representation, and one cannot help feeling that in Davies’ hands what began as a single rusty nail that was duplicated by wax casts, has taken on the votive function of a candle in a church for the lives dispossessed at Capel Celyn”.

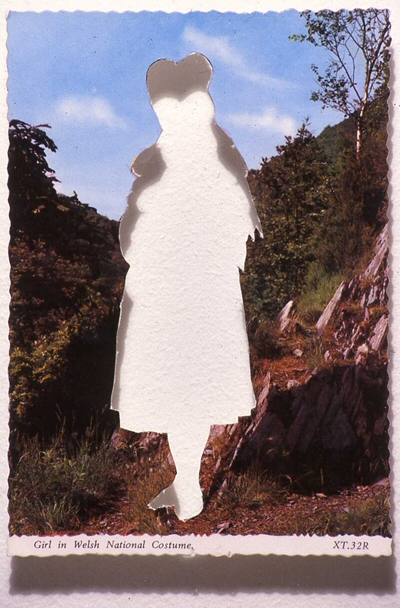

Another work that shows his response to current events is the video piece “Drumming” of 2003, where a drum is beaten loudly and continuously. Made to be placed near the famous statue "Drummer Boy" by Sir William Goscombe John in the National Museum & Gallery, Cardiff, it shows us how art reflected its time, a propagandist drum, beating a roll call to arms that is repeated today as an ironic comment about the propaganda that once again has taken us to war. In a series of postcard ‘interventions’ (a series of twelve was purchased for CASW in 2003) Tim Davies has turned his attention to that Welsh icon of the tourist postcard, the Welsh Lady. In these found postcards, the central figure or group of figures are meticulously removed, leaving a neat and empty, yet recognizable silhouette. Getting rid of these outmoded views of Wales, he seems to say, lets us see the reality that surrounds them. Also on the purchased list in 2003 was a series of early Peter Finnemore work where political engagement was most obvious. The work, “Lesson 56 - Wales” (1998) is a series of six C.Type colour prints on aluminium, and feature pages from his grandmothers school history textbooks. They contain such gems as; ‘When speaking of England it is understood that Wales is also meant.’ and show the majority of the atlas coloured the pink of the British Empire. Finnemore has gone on to represent Wales at the Venice Biennale exhibition of 2005 with a series of humorous yet telling short films.

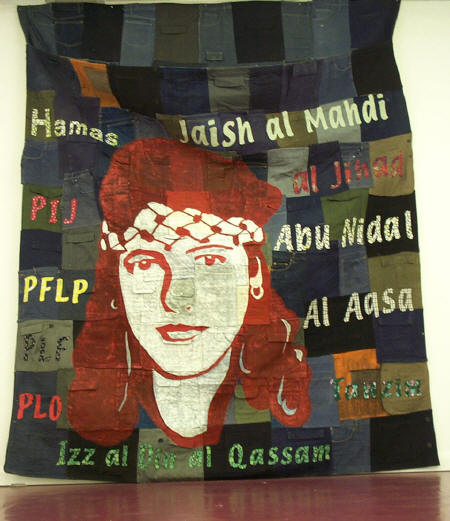

David Garner began his

political engagement in his ‘milltir sgwar’ (square mile) of mining town

Blackwood, dealing with industrial decline, new short stay technology industries

and his own father’s death from pneumoconiosis contracted from year’s

underground. His “Political Games 2” (1995) is in the CASW collection, an iron

target filled with discarded work boots. “Pockets of Resistance”

(2003-04) is a huge tarpaulin pocket covered with pockets from everyday garments

(picture below left), and was first exhibited in the exhibition FACT,

held in a disused shop in Swansea in 2004. Names of various resistance movements

are attached in fabrics associated with women's clothing, together with the

iconic face of the first female suicide bomber, Wafa Idris. “They Shoot Children

Don't They?” (2003-04) is a welded steel framed globe in which a video

monitor is suspended which repeats a five minute loop of footage extracted from

the banned Arab film,

This is not an issue for one people and one place only, it is global - the rope that binds us is unravelling. The work of artists like Garner points the finger at this continuing human folly. It is cultural and political imperialism, multi-nationals and greed that should legitimately be described by that line, their behaviour is indeed ‘consistent with no future’. The future looks bleak for us all, and the threat to our environment by far exceeds the threat of terrorism. Whether art can make a difference is probably a moot point, but without art that challenges, then we have even less to look out for that will be of interest in this homogenised world. Art offers alternatives to the tired imagination, so that some recipients of the ‘message’ can gain another view on the world, one that might indeed effect the real politics at some point. Over the course of the twentieth century art had become largely removed (and has removed itself) from the overtly political concerns of the day to day. An ideological conspiracy in effect, isolated art in institutions much like ‘ivory towers’. Today, more and more artists (in Wales and elsewhere) are becoming genuinely engaged with the wider community and with issues such as the environment. It seems that right now, we are of the generation who can see the end, truly the catastrophic end of civilisation as we know it within a century - this 'political' reality - of global warming, surely becomes the theme of Art. As more people question the way we live and see that a change is inevitable, voluntarily or not; they see the art that was practised in the West (and now globally exported) to be part of the same destructive self-indulgent system. It becomes clear that alternative ways of thinking and being must be offered by artist; this is the greatest political challenge of all. [i] See The Visual Culture of Wales 3 vols. Peter Lord (Cardiff, University of Wales Press, 1998-2000-2003). [ii] See The Layers of a Landscape by Shelagh Hourahane pp57, Certain Welsh Artists ed. Iwan Bala (Bridgend, Seren Books, 1999). [iii] See Maps, Myths and the Politics of Art by Shelagh Hourahane pp 67, Certain Welsh Artists ed. Iwan Bala (Bridgend, Seren Books, 1999). [iv] See pp 66 Certain Welsh Artists ed. Iwan Bala (Bridgend, Seren Books, 1999). [v] See Josef Beuys and the Celtic World. Sean Rainbird (London, Tate 2005). [vi] See Fire Anne Price-Owen pp 50, Process (Bridgend, Seren Books, 2002). |

|

|

I had

myself been involved in a small way in some of these events, an altogether more

frightening and thrilling experience, and riskier by far, than painting slogans

onto canvasses, (which is what Beca, in effect, were doing). However, as a

focusing of energy, as proof that such sensibilities could be accommodated in

the world of art in Wales, Beca sounded a clarion call. Davies’s protest in 1977

was directed at the Welsh Arts Council, who had organised an ‘international’

performance art event at the Eisteddfod, including Joseph Beuys and many other

‘names’ but excluding Welsh artists. In the photograph taken of this

event, the renowned Italian artist Mario Merz is seen confronting Davies.

I had

myself been involved in a small way in some of these events, an altogether more

frightening and thrilling experience, and riskier by far, than painting slogans

onto canvasses, (which is what Beca, in effect, were doing). However, as a

focusing of energy, as proof that such sensibilities could be accommodated in

the world of art in Wales, Beca sounded a clarion call. Davies’s protest in 1977

was directed at the Welsh Arts Council, who had organised an ‘international’

performance art event at the Eisteddfod, including Joseph Beuys and many other

‘names’ but excluding Welsh artists. In the photograph taken of this

event, the renowned Italian artist Mario Merz is seen confronting Davies. With

his charismatic presence, theoretical lectures, blackboard diagrams and much-mythologised

persona, the aforementioned German artist and ‘activist’ Joseph Beuys was an

influence in the 70’s and 80’s too. Despite the fact that he was not actually

present at the Wrexham Eisteddfod, Beuys had shown considerable interest in the

‘Celtic Fringe’.

With

his charismatic presence, theoretical lectures, blackboard diagrams and much-mythologised

persona, the aforementioned German artist and ‘activist’ Joseph Beuys was an

influence in the 70’s and 80’s too. Despite the fact that he was not actually

present at the Wrexham Eisteddfod, Beuys had shown considerable interest in the

‘Celtic Fringe’.

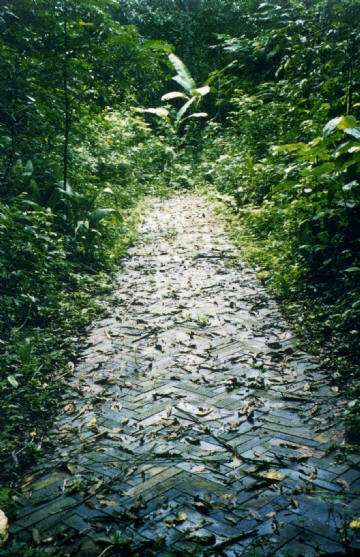

The

“Returned Parquet” piece (picture right) made for Poustina Earth Art

project in Belize in 1999 emphasizes the process of political awareness that is

part and parcel of Davies' work. Looking out for new materials to use, Davies

found a pile of salvaged mahogany blocks in a yard outside Swansea. He realized

the significance of these blocks: once the floor of a grand house in south

Wales, made from wood cut down by slave labour in Central America before being

shipped to Europe, perhaps via the port of Cardiff. He made a decision to ship

it all back to Belize. Aided by an Arts Council of Wales grant, he duly shipped

the blocks back to the forest. There he laid them out as a pathway, where they

remain, gradually being truly reclaimed by the undergrowth and the termites.

The

“Returned Parquet” piece (picture right) made for Poustina Earth Art

project in Belize in 1999 emphasizes the process of political awareness that is

part and parcel of Davies' work. Looking out for new materials to use, Davies

found a pile of salvaged mahogany blocks in a yard outside Swansea. He realized

the significance of these blocks: once the floor of a grand house in south

Wales, made from wood cut down by slave labour in Central America before being

shipped to Europe, perhaps via the port of Cardiff. He made a decision to ship

it all back to Belize. Aided by an Arts Council of Wales grant, he duly shipped

the blocks back to the forest. There he laid them out as a pathway, where they

remain, gradually being truly reclaimed by the undergrowth and the termites.