|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Horizon Wales: Visual Art and the

Postcolonial

1 Is Wales postcolonial? Is any place? Transnational corporations have become the new exponents of colonialism, and with it the idea of a global visual culture, expounded by large powerhouse art galleries and Biennales that spring up in every corner of the developed world. Where is Wales? Its argued that historically Wales is a province and not a colony. Is that why our art is assumed to be provincial? Perhaps the question we need ask is, can we become ‘post-provincial’? Whatever the argument, it's difficult to deny an ongoing cultural colonialism, which leads to the belief that Postcolonialism needs to be a state of mind as much, if not more than, a political position. Wales may not have seen armies of occupation for some time but it has felt the economic and cultural consequence of Empire and suffers its paralysing side-effect, the colonised mentality. It would be foolish to separate culture from this wider context and visual art in Wales has reflected this psychological inheritance: Welsh art depicts an enforced duality, revealing on the one hand a ‘culture shame’ that induces an eagerness to please, to adopt the rhetoric of British patriotism and to assimilate, and on the other to espouse a stubborn avowal of difference and an insistence upon cultural Otherness. Both acquiescent and resistant, these are traits of the colonised. Value is still accorded to those who 'escape' and succeed elsewhere, and this, though an economic necessity to begin with becomes very much a cultural condition. The term 'Welsh' art is now often substituted with 'Wales' art, a concept free of ethnic overtones and perhaps a more realistic label with which to describe the art scene as it is, but it does imply an avoidance of the issue of being 'Welsh', going more for a 'Made in Wales' uniformity. Even if the backgrounds of individual practitioners within what could be called; 'Wales-Art-World ' are multivarious, I would argue that the institutions, the collective behavior, the pathology that animates this world still reflects vestiges of its unreconstructed 'Welsh' make-up - its colonised traits. Its duality is revealed by, on one hand an overcompensating boastfulness, on the other an adolescent dependence. As in other fields, a lack of entrepreneurial vision and selfless belief stunts the support system that in other parts of the world promotes artists careers. In short, vision and support on a political and financial level is needed. Grand gestures are followed by dithering and collapse, as in the case of Cardiff's Centre for Visual Art or the National Botanic Gardens, or Zaha Hadid's cancelled Opera House design.

In this contemporary 'Wales', postcolonial discourse can be an useful tool, a ‘discursive terminology’ that may help us to understand a complex pathology, or at least to understand art production in that light. It also links with interesting and dynamic art produced in other cultures that can more unequivocally be termed postcolonial and involve us in critical dissemination. Such associations open up new possibilities and new references for our visual artists, as they do, of course, for all producers of culture. The space of one essay does not allow for a thorough analysis of all these new or potential influences, nor on individual artists; however, it may catalogue possible subjects and scenarios for a discussion that is long overdue in the context of visual art in Wales. It should have a bearing on any discussions on the establishing of a National Gallery of Welsh art for example, what form would it take, which artists will be shown and which ones remain in storage? Despite the fact that postcolonial studies concentrate primarily on countries in the so-called ‘third world’ it is clear that the long-term affects of postcolonialism function also within areas of the ‘first world’. Trinh T. Minh-Ha, a Vietnamese film maker now working in the USA, has said of her own situation and that of many others who have migrated to the West, ‘There is a Third World in every First World, and vice versa.’[iii] A legacy of colonialism is a new 'nomadism'; artists increasingly cross cultural and political borders forming a 'trans-national' exchange of ideas and conditions.

2 Artists, by and large, perform to suit the conditions of the time they live in, and are always full of desire to express their individual and collective identity. The fulfillment of that desire in Wales has been on view in the Arts and Crafts pavilions of each National Eisteddfod since 1990. Yet artists in Wales, both Welsh and non-Welsh rarely contemplate nor engage with the notion of Wales as colony, post or otherwise, unless it directly impacts on their 'professional development'. This may be due to the fact that the colonized state of mind is so deep-rooted and seemingly so well disguised. In postcolonial language it is a case of ‘subaltern mentality’. Artists who are Welsh speakers tend to be more conscious of the condition, perhaps because they retain a certain sense of ‘difference’. Historically, the industrial working classes of Wales (primarily though not exclusively non-Welsh speaking in the twentieth century) have seen their subaltern situation as a ‘class’ rather than a ‘culture’ issue, and many artists in Wales come from that cultural formation.

Artists face the problems associated with being ‘peripheral’ to the centers of art production and marketing and on the whole prefer to avoid being labeled in any way that would deny them the widest field of play. We might compare this instinct to the resistance of black British artists to being ghettoized into ‘special’ exhibitions, rather than being viewed as part of mainstream British art, to which (all being equal) we all contribute. There has therefore been a tendency for artists to believe that success can only be measured on the ‘macro’ scale, British rather than Welsh, a tendency emphasized by the attitudes of the London press towards the ‘periphery’. There are signs that this tendency is entrenched and endemic. The selectors of Wales' first Venice Biennale exhibition, Further in 2003, were criticized in Wales for ignoring the internal community of artists. The two Welsh (indeed Welsh speaking) artists selected, Cerith Wyn Evans and Bethan Huws have created their careers outside Wales. Wales' presence at the Biennale warrants celebration, it is a statement that identifies Wales as an independent entity, but at the same time seems too eager to appear 'internationalist' at the expense of recognizing and promoting its own 'underprivileged' artists. Again partly resistant, partly acquiescent, an indicator of a lack of confidence rather than a much vaunted 'new confidence'. Such conflict reflects the duality at the heart of postmodernism, between cultural identity based on 'roots' in one corner and a trans-national, non-specific and non-attached identity in the other. Wyn Evans' piece at Venice, Cleave 03 utilized a WW2 searchlight beam shot skywards relaying in Morse code, words from Ellis Wynne's canonical Welsh text of 1703, Gweledigaethau y Bardd Cwsc (Visions of the Sleeping Bard) is a translation of a translation. The work quoted is itself based on a 1627 Spanish text, Suenos y Discursos by Fransisco de Quevedo encountered by Wynne in an English translation. The intermittent beam signaled Wales' arrival in Venice as much as it signaled the diffusion of one language translated into another, text into art and, poignantly it seemed to me, Cymraeg into thin air. The threat of homogenization and the loss of cultural independence have been resisted: an indigenous ‘alternative modernism’ was practiced throughout the last century in Latin America, and in Europe itself, Basque culture, for example, produced art ‘authentic’ to its own cultural experience evidenced in the work of Ibarolla, Chillida and Jorge de Oteiza, which is nonetheless international in its scope.

In any society, in any particular period, there is a central system of practices, meanings and values, which we can properly call dominant and effective. This implies no presumption about its value. It is this central system that formulates the selective tradition; that which, within the terms of an effective dominant culture, is always passed off as ‘the tradition’, ‘the significant past’. [v]

In opposition to this ‘selective tradition’ there exists a ‘residual culture’, which is reactionary, and an emergent culture’ which is revolutionary. In this context that which is avant-garde in art is an ‘emergent’ and culturally revolutionary force of revitalization, which offers an alternative ‘tradition’ to that of moribund and lethargic monumental systems. The production of art that questions the hegemony of the state or the market, or dismantles prejudices, racism and imperialism, can also been seen as the act of ‘compensating the canon’, that is of offering alternative variants to the accepted and ‘selective tradition’. Wales has artists who are doing that now, joining a growing movement of artists who seek to examine issues of their particular identity, political and gender borders and the nature of the global market. It should be stressed then, that art that challenges the 'selective tradition' as it exists in Wales, is not bound by the situation in Wales only, but reflects artistic concerns of many artists in many places. In addition, it is hard to imagine another discipline that has undergone such radical shifts in the parameters of what it can be made of or be about as we have seen in visual art over the last forty years.

3 Postcolonialism and its ally, postmodernist art, has encouraged hybridity and syncretism or, to give it a popular name; 'Fusion'. Artist are able to absorb from their indigenous culture, (often many-layered and depending on multiple understandings of the ‘indigenous’), from colonialist culture and from global culture generally, giving rise to a new and vibrant art language that speaks of the complex here and now: in Havana, in Harare, in Dublin, in Cardiff. Postcolonial confidence gives free reign to the appropriative appetites of such artists, unburdened by guilt, either of their own history and identity or of that imposed upon them by the coloniser. Issues of identity, it is argued, can be both sources of inspiration and inhibitors: once identity is established or reaffirmed we are then free of it, or so we may hope. The concept of postcolonial ‘hybridity’ proposes a new form of identity. According to the Cuban writer Gerardo Mosquera,

The ‘liberation’ of identity allows us to understand it in a more flexible manner, erasing the essentialisms that forever limited its theory and practice. This is particularly useful for postcolonial cultures, frequently caught between the ‘authenticity’ of their ‘roots’ and the ‘colonialism’ of contemporary life. Complexes and incomprehensions disappear in the creation of new culture, inventing identity according to the syncretism characteristic of current processes.[vi]

We might interpret such initiatives as the g39 exhibition space in Cardiff, or the (brief) appearance of ‘Welsh’ artists alongside international ‘names’ at the ill fated Centre for Visual Art as instances of postcolonial ‘mixedness’. We might look at the phenomenon of the ‘intimate outsider’ - the artists who choose to make Wales their home and source of inspiration - as a reflection of a new ‘mixedness’, rather than as merely the continuation of a very old practice. Or we may have to look deeper to find in Wales an authentic 'new culture' as Mosquera calls it. Issues seen from the perspective of ‘Otherness’ or ‘difference’ are themselves being fetishised by the marketplace. Jean Fisher argues that,

‘cultural marginality is no longer a problem of invisibility but one of excess visibility in terms of a reading of cultural difference that is too easily marketable’[vii].

In a sense, art produced to question and challenge the Eurocentric hierarchy of the West becomes ‘collectable’. Attempts to liberate art from market forces through process based art forms, installations, and revivals of the Fluxus ‘happenings’ flourish, all of which are relatively resistant to commodification. But of course, for those who understood culture as the authoritative, autonomous and privileged object of formalist modernism, this was not ‘art’. In Wales, an instance of the noncommodified ‘event’ was introduced by the Artists’ Project, established in the early 90s with close links to the Artists Museum in Lodz, Poland, which was set up to support Solidarnosc. The Artists Project heralded a movement towards large site-specific events, with artists traveling from all over the world to create work on the spot, collaborating and living together for a week or two, then dispersing. By heading an initiative to create a European network of like-minded, artist-led bodies, it proves that Wales can lead the way in Europe. The Artists’ Project hosted a major event on New York’s Staten Island in June of 2002, and another event is planned back in Wales for 2005. Locws International has held its second site specific event in Swansea, in a similar venture. Other instances of art making inroads into communities, outside of galleries, might include the Harlech Biennale or Cywaith Cymru 's residencies. These events bring together local artists and invited artists from beyond Wales’ borders.

In the same article Hourahane quotes the historian and writer Peter Stead as having recently ‘proposed that the road to a healthy future for Wales might lie primarily with cultural activity, rather than through political solutions,’ and adds that, in justifying this statement, Stead ‘also expressed the opinion that it is the visual arts, which are presently the most dynamic of the art forms in Wales.’[viii] If this is indeed the case, then it must be said that from the point of view of the practitioner, Wales is not currently providing much in terms of a quid pro quo for the dynamic leadership it expects from its visual artists. Very few artists in Wales today can hope to make a living from the sale of art work alone: the market for Welsh art, though growing, is still small and on the whole, conservative.

4 The art historian Peter Lord has made an invaluable contribution to the process of decolonisation, laying claim to representation by writing from within the culture rather than pronouncing from the outside, and placing art firmly into a social context. His history nevertheless terminates in 1960 on the basis that,

The rapid expansion of government funding of higher education changed the nature of art colleges by drawing in large numbers of young teachers, mostly from outside Wales, at a time when ideas about art as an international language was already marginalizing those for whom cultural individuation was the central concern. [ix]

This argument suggests that it is no longer possible for the college trained artists to ‘visualize the nation’ of Wales in the way that they might have done before 1960. Yet it is hard to imagine a time when Welsh artists have been free from the influence of art produced outside Wales, but for all that they still, if they chose to, made art that was relevant to their own specific experience, and they continue to do so today. The remarkable survival of Wales’ sense of identity, in the face of extreme external pressure to erase it, is due to each generation’s discovery of a voice of protest. Young artists reinvent the meaning of partisanship according to an international climate, whether that climate be Classicism, Romanticism, Modernism or, as now, Postmodernism. Whilst it is true that Welsh art colleges in the 1960s and 1970s tended to be Anglo/Eurocentric, there was also a rapid politicization of students that made artists of my own generation (I went to Cardiff Art College in 1976) aware through Vietnam to Nicaragua of American imperialism, of Feminism, ‘anarchy in the UK’, the tyranny of capitalism and the erosion of the environment. Despite the influence of formalism, politics was creeping into art. A small number of art students in the 70s were also aware of Welsh political issues, though it was not deemed a subject fit for serious exploration: a great many more students are finding that it can be explored today. Yet for students from Bangor, Carmarthen or Bala at Cardiff, the decline of the Welsh language and culture, and issues of nationalism, republicanism, socialism, were as important (if not more so) than lithography, Jackson Pollock or the Tate bricks. Thus I would argue that, despite the influence of a selective tradition both taught and consumed via art magazines and books, the work and teaching of Paul Davies, Ivor Davies, Peter Prendergast and Mary Lloyd Jones from the 70s onwards and, more recently, of Lois Williams, Tim Davies, David Garner, Peter Finnemore and Carwyn Evans is as much an influence and as authentic a visualization of Wales at this particular time as was Christopher Williams’ or Hugh Hughes’ to theirs, and more democratically diverse as befits this period. Landscape painting has been pre-eminently the art form most associated with ‘visualizing’ Wales; for the world outside if not for itself, the romantic beauty of its terrain and the interest of its industrial panorama constituted its main claim to attention. Since the Welsh born Richard Wilson ‘invented’ it, landscape painting, both poetic and prosaic, has been central to the visual production of Wales. Landscape, as the writer Emyr Humphreys says,

'immortalizes experience, so as the stream of life flows on, and we are carried with it, the residue that it leaves in landscape is myth. This is what human beings of the past left behind them; and what they left behind them is now part of our present. So it’s a deposit, a vital deposit, a raw material in the literal sense. Just as you dig down for gold, or coal, you dig down for myth as well. It is a raw material vital for your well-being’.[x]

The same was certainly true of the Romantic landscape artist; further, twentieth-century landscape painting in Wales can be said to be not only a continuation of such ‘tourism’, but also a result of the realization in the 1930s that the British Empire was in sharp decline. Artists increasingly began to look inwards, to the ‘home islands’, in direct proportion to the decreasing opportunity to exercise the outward gaze of imperialism. But Wynn Thomas suggests that Humphreys, in his poetry collection Landscapes, sought to reclaim the land for its people; the volume was

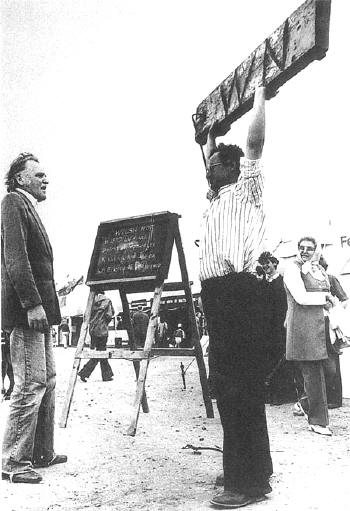

In what can be seen as a parallel activity, a homology, visual artists have also been slowly reclaiming that landscape and with it proclaiming a liberated identity. In the 1970s, the Beca group of artists, which included brothers Peter and Paul Davies (picture below left) and Ivor Davies, set out to make political Welsh art. Radical in format, they drew on the influence of Fluxus and the Paris underground of the 60's, political on specific Welsh issues and operating in a way very like much contemporary Latin American art. These works can be interpreted as traditional 'landscape' only in the loosest sense, but they are also real and truthful in their descriptions of the wider landscape of Wales, in its metaphysical as well as physical terrain. Mary Lloyd Jones' work which closer resembles the tradition of watercolour and oil 'studies' of the landscape, nevertheless shows a radical departure in the context in which she works. She has dug deep to expose the palimpsest history located in the ‘deep time’ of her home environment by severely abstracting nature, creating map like patterns and forms that operate similarly to the 'songline' paintings of Australian Aboriginal art; in her work Iron Age sites and traces of poetry become visible once more, reminding us, in a tribal way, of ancestors and a sense of rootedness. A similar aim underlies the paintings of Geoffrey Olsen, though his work is as much about the layering processes of painting itself, as equivalent, rather than illustration of the layers of history superimposed onto the land by historic time. He is an artist who has taken this palimpsest background that being Welsh accredits us with, and moving out into the world teaching and exhibiting, takes it with him.

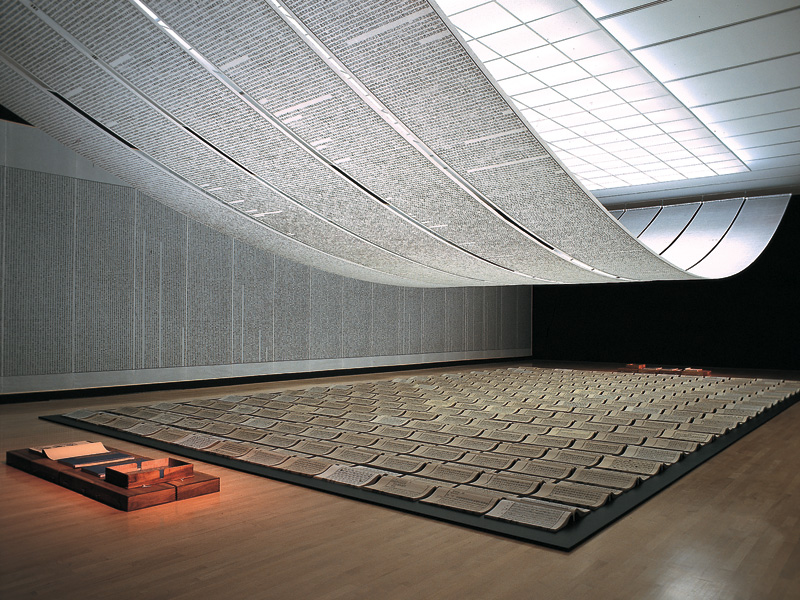

5 Other nations in the fraternity of the postcolonial have come to regard Wales as a fellow traveler and not as a wet western province of England. Hence Welsh exhibitions are organized abroad under the premise that we are an autonomous entity - not always, of course, a premise shared back home. An exhibition of Welsh art funded by the British Council and creatively curated by Alex Farquharson was seen in Zagreb in 2002, and an exhibition of ‘new generation’ artists from Wales was held in Milan in 2000. It would appear that there is an attempt on some levels in the British establishment to appear benevolently multicultural and show Britain in all its multifarious constituent parts, rather than be merely London-centric; on the other hand this development may rather mark a reactionary attempt at a Union of Diversity, a late redefinition of ‘Britishness’ as a more inclusive identity. A more recent development in Wales is the establishment of the Artes Mundi prize, at £40,000 amongst the world's largest, brought about through the endeavors of artist and enabler, William Wilkins. Through the generosity of the Derek Williams Trust, another £30,000 has been made available for purchases to the National Museum. Added to the Venice Biennale venture, this award gives Wales a platform to proclaim a new dedication to visual arts, certainly a new concept for many. The shortlist of ten artists for the first award holds a particular relevance to the view of Wales that I have outlined above. Of the ten, only Tim Davies is European by birth, several are from the Far East, one from South Africa. All are committed to making work that furthers our understanding of the human condition in this complex age of global cross-fertilization. The award went to Chinese artist Xu Bing.

By bringing short listed artists previously unseen in Britain to work and exhibit in Wales from areas hitherto peripheral to the traditional centres, the aim of the prize is two handed. It shows the world that we in Wales love and respect contemporary art whilst also showing the 'we in Wales' why we should love and respect contemporary art. The art celebrated, as selector Declan McGonagle has said, is 'in the world, but rooted to a particular place' and importantly is about real issues. McGonagle's ambitious vision of a 'new modernism' underpins the initiative and implies a shift in perspective, so that there is a more equitable and 'negotiated space' replacing the notion of centre and periphery. The National Museum & Gallery of Wales which will host these artists, placed as it is in the complex of institutions in Cathays Park that include the Law Courts, City Hall, Welsh Office and Temple of Peace, is ostensibly a statement of Cardiff’s status in the world, displaying the visionary optimism of its Edwardian industrialist city fathers. Alternatively it could itself be seen as an instance of colonial symbolism. There are those who argue that it still is a colonial institution that has made little attempt in the past to be truly national in the Welsh sense, but currently it seems to be making attempts to convince us otherwise, and to metamorphose into an institution worthy of a postcolonial Wales. Whilst the current debate concerning the extending of the NMGW, literally and metaphorically, into a National Gallery to house a permanent collection is worthy, it is decades late. We must also deal with the lack of any large, prestigious art space in the capital city for the display of major touring exhibitions; for it will only be when Wales hosts visiting artists, and Wales' artists gain entry into a wider world, that we can assert a ‘visible’ presence. It goes without saying that we need a building that might be called the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Welsh Art to cement our relationship to the international community, echoing the optimism and vision of those Cardiff city fathers a century ago. If not like Dublin, Edinburgh, or Bilbao, Cardiff in this respect should at the very least be like Salford, Gateshead and Walsall. There has to be a note of caution here however, culturally and economically we are being colonized by the United States and by multinational corporations and multinational art. No one would deny the importance of showing international art in Wales: it is essential in order to draw audiences (which the Artes Mundi experience proves can be done) and garner the much needed press and critical interest. However, the ‘international art’ should be of relevance to Wales’ particular position, and not just a roll call of those reified artists that we see in every major gallery in every major city in the world. It seems that the Artes Mundi prize might help achieve this aim. Of course many artists of international stature have passed through Wales before now. Turner prize nominees Mona Hatoum and Cornellia Parker both benefited from a fellowship at Cardiff's College of Art, that allowed them time and funding to develop their now high profile careers but are reluctant to acknowledge the time spent in Wales, which has yet to attain the 'kudos' required to be impressive on an artists C.V. Others however have found Wales conductive to their practice. Andre Stitt was drawn to Wales by its reputation for physical performance theatre, exemplified by companies like Brith Gof and Moving Being and is surprised to find how unaware we are of our own distinctive tradition.

6 The title of this essay comes from a series of drawings and paintings of my own depicting an island on a distant horizon, its outline based on the map of Wales and sometimes resembling an animal skull, or a ruined castle, its shape shifts to become a heart or a claw grasping for roots. The iconic island depicted is a barren piece of land that needs revitalizing, a large percentage of its mass is submerged, either hidden or drowned. It's an image of duality, a place onto which we can project our hopes and our disappointments. But it is also separated from the viewer by a stretch of water, and suggests an unattainable and 'fantasy island' like 'Gwales' in the Mabinogi, a free Wales, free of care, but also a diverting reverie, a mirage. It marks a stage in the complex and confusing process of decolonisation. Doubtlessly the postcolonial discourse as currently practiced in the wider world offers Wales a necessary tool to discuss its relevant position and writing on art can only be encouraged by the recent spate of books published in both Welsh and English. Students are becoming increasingly aware, in graduate and postgraduate studies, of the culturally specific argument. In papers given at a conference by the Institute of International Visual Arts, ‘Global Visions’, Gilane Tawadros, whilst dismantling the construct of cultural homogeneity, concedes that:

‘the forces of nationalism and internationalism have been powerful catalysts of change and regeneration in our past century, but only when they grow out of present realities and not abstract concepts floating somewhere high up in the stratosphere, far removed from lived experience.’[xiii]

The work of artists here today proves that Wales’ present realities can be harnessed and used as pointers for change and regeneration, as long as they are truthfully represented. We would have to conclude that truly postcolonial art from Wales might have little to do with or about Wales, that the issues will have changed. For artists of my generation, who have made it our subject, that might be disappointing, and whether we agree or not that that stage is upon us is immaterial, the art gets produced anyway and only time and a sharp critical evaluation will tell whether it truly reflects our situation. Raymond Williams, I am sure, would have much to say at this juncture in Welsh history. In a defining statement that echoes Tawadros, Williams said, ‘Anything as deep as a dominant structure of feeling is only changed by active new experience.’[xiv] The dominant structures of feeling in Wales are shifting: on the surface a new experience of feeling and imagination, a new optimism and pride, at least on a cultural level, is blossoming. Nowhere is this more evident than in the field of visual art. The big initiatives are without doubt significant, but also, on the ground the swelling number of artists and audience and buyers, of public art projects and residencies is proof that, if not postcolonial we are in Wales certainly post-provincial.Yet this optimism is a fragile growth that at the moment appears to be grafted onto the surface of Welsh life. It must find deeper roots and become a more substantial reality, so that a new structure of feeling may replace that state of mind that has burdened us for so long, that of the colonized ‘ambivalence’, or, in more inflammatory parlance; ‘culture cringe’. When that process of change has taken place, then we will truly be able to say that we are postcolonial, should that term still be in existence. [i] Robert.C. Morgan, The End of the Art World, Allworth Press 1998. p193 [ii] Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967. [iii] Trinh T Minh-Ha, ‘Discussions in Contemporary Culture’, in Hal Foster ed., Discussions in Contemporary Culture, Seattle: Bay Press, 1987. [iv] Iwan Bala ed Certain Welsh Artists, Seren, 1999. [v] Raymond Williams, ‘Base and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory’ in Problems in Materialism and Culture, Selected Essays, London: Verso, 1980, pp. 38-39. 8Gerardo Mosquera, ‘My Homeland: An essay on Ernesto Pujol’, Third Text, Autumn/Winter 1984. 9Jean Fisher, ‘The Syncretic Turn: Cross - Cultural Practices in the Age of Multiculturalism’ in New Histories, Boston: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1996. [viii] Shelagh Hourahane, ‘Impact of the Printed Word’, Agenda, Spring 2001, 57. [ix] Peter Lord, ‘Introduction’, Imaging the Nation, Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2000, p. 9. [x] M. Wynn Thomas, ed., Emyr Humphreys: Conversations and Reflections, Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2002, p. 11. [xi] Ibid, p. 8 [xii] See my essay ‘Capel Celyn: A Collective Trauma Visualized’ in Planet, 152, April/May 2002, pp. 35-43. [xiii] Gilane Tawadros, ‘The Case of the Missing Body, a Cultural Mystery in Several Parts’ in Global Visions. Towards a New Internationalism in Visual Arts, London: Kala Press, 1994. [xiv] Raymond Williams, Critical Perspectives, ed. Terry Eagleton, London: Polity Press, 1989, p 108.

|

|

|

The book

Certain Welsh Artists

The book

Certain Welsh Artists Events, unlike

monuments, are of their nature ephemeral and need recording;

contemporary art needs contextualizing; and both these functions are

usually the preserve of the critic. Artists need writers of caliber,

like Mosquera in Cuba, not only to write their history, but also to

write them into history. To do that, we need publications and books that

encourage writing on the visual arts specifically. In the Winter 2000/01

issue of Agenda, the journal of the Institute of Welsh Affairs,

Shelagh Hourahane, herself an incisive writer on visual art, argues

that: ‘there is a need for a serious vehicle for dissemination and

discussion of ideas,’ because the complex, multi-faceted art world of

today relies more and more on this dissemination of ideas and

information. Existing art magazines in the UK are focused parochially on

central London, though the developments in Glasgow or Newcastle are

beginning to make inroads, the comedy cliché of 'province' Wales still

has currency. This was noticeable even when as accomplished an artist as

Shani Rhys James is reviewed on winning the Jerwood Prize in London in

2003. Born in Australia she has chosen to live in her father's homeland.

Her abandonment of London for rural mid-Wales obviously does not

contribute to her acceptance by the metropolitan critics, despite the

fact that this is a crucial aspect of her work, which reflect very much

on her own situation, an existential outsider staring out of her

canvasses, defiant and accusing.. Her face, her demeanor, her physical

stature, seem to encapsulate certain traits attributed to the Welsh by

the metropolitan English, a stubborn, unyielding 'otherness' that is

hard for them to accept.

Events, unlike

monuments, are of their nature ephemeral and need recording;

contemporary art needs contextualizing; and both these functions are

usually the preserve of the critic. Artists need writers of caliber,

like Mosquera in Cuba, not only to write their history, but also to

write them into history. To do that, we need publications and books that

encourage writing on the visual arts specifically. In the Winter 2000/01

issue of Agenda, the journal of the Institute of Welsh Affairs,

Shelagh Hourahane, herself an incisive writer on visual art, argues

that: ‘there is a need for a serious vehicle for dissemination and

discussion of ideas,’ because the complex, multi-faceted art world of

today relies more and more on this dissemination of ideas and

information. Existing art magazines in the UK are focused parochially on

central London, though the developments in Glasgow or Newcastle are

beginning to make inroads, the comedy cliché of 'province' Wales still

has currency. This was noticeable even when as accomplished an artist as

Shani Rhys James is reviewed on winning the Jerwood Prize in London in

2003. Born in Australia she has chosen to live in her father's homeland.

Her abandonment of London for rural mid-Wales obviously does not

contribute to her acceptance by the metropolitan critics, despite the

fact that this is a crucial aspect of her work, which reflect very much

on her own situation, an existential outsider staring out of her

canvasses, defiant and accusing.. Her face, her demeanor, her physical

stature, seem to encapsulate certain traits attributed to the Welsh by

the metropolitan English, a stubborn, unyielding 'otherness' that is

hard for them to accept.