The Gypsy Switch (1981-1982)

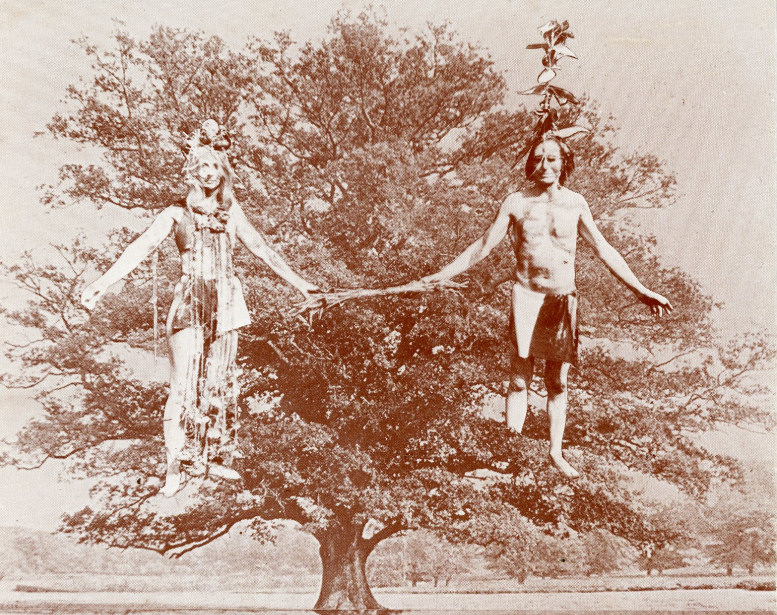

In 1981, whilst still working

with husband Bruce Lacey, Jill Smith had an exhibition at the Serpentine

Gallery called 'Cycles of the Serpent'. At the time she was known as Jill Bruce, but in 1982

things started to change, as she explains in this

excerpt from her 2019 book 'The Gypsy Switch and Other Ritual Journeys'.

Reading back over fragments

written in old diaries I am surprised to realise how stressed I was in

1981, suffering what now seems to be clinical depression. I was totally

lacking in energy, exhausted, unable to cope with all the work we were

doing: all the fairs and that year, a major exhibition at the Serpentine

Gallery in London, the smaller one in the Norwich, then another major

one at the Acme gallery in Covent Garden (pictures below x2). Since then, I have forgotten

how I felt at that time, remembering only the positive. Little survives

of what I wrote, but I seem to have been overwhelmed, worried sick about

the goats, wanting simply to be with the earth, my plants, trees and

animals; rushing about here, there and everywhere, but needing just to

be still, feeling claustrophobic and trapped. I wanted desperately to go

off on my own, to drive off and get away, yet at that point not seeming

able to. I would be totally down, unable to do anything at all, then

suddenly full of a new energy and happiness, able to do everything which

had to be done, and my goodness, so much did get done that year!

The Serpentine exhibition (Cycles of the Serpent) was a bad experience.

We created a serpentine structure out of long poles and in and on it

placed objects, photos etc. about the turning cycles of the year as we

lived them at Brentwood Farm. I had a lot of personal writing in it;

lots of photographs of the plants, vegetables, fruit, goats, chickens

and the important events in our country calendar. I made ‘ladies’

representing the elements (and me), and dressed them in my costumes.

Bruce asked for some display stands and exhibited our goat and horse

shit as ‘sacred objects’ (we were looking after a friend’s pony). I felt

uncomfortable about this but didn’t say anything and of course the media

seized on it, there was a huge hoo-ha and the whole exhibition was

ridiculed. I had put so much of my self into it and then had it turned

into a joke. Bruce, the comedian, the professional British eccentric,

had got publicity but destroyed my dream. I think this was one of many

‘last straws’ of the relationship as far as I was concerned. I often

felt our performances were treated as a joke, and the more they became

real for me, the more I wanted to withdraw from them being perceived

that way.

However, later in the year, the Acme exhibition was filled with a

massive energy which strengthened my ability to be myself. For years I

had felt trapped in my marriage and working relationship, with no real

friends or life outside it, but feared walking away into a void. But

after the Acme I started to have a life of my own, went out with others

and got to know many more people. It was at this point that the Dzog

Chen teachings and Goddess concepts became a big part of my life,

bringing a different focus and direction to all my random craziness,

which now started to fall into some kind of pattern and shape. But it

was only a start.

During the winter of ‘81/’82 I was swept along by a tide of

inevitability, no longer having to make decisions. I flew free of the

cage and just followed where there seemed no doubt. I can’t now find

records of exactly what I did or where I went, but made my first

excursions into the landscape alone. In the early days I drove to them

in my Morrie van but then began to go off on foot. Previously I had been

driven everywhere by Bruce, and hadn’t travelled on public transport,

apart from London buses and underground and that one train journey to

get the seaweed, so finding out how to get about on my own without

driving was a huge challenge.

Going to Avebury and the West Kennet long barrow by train and bus, I

felt so liberated, so much more in control of my life. I slept for the

first time in West Kennet and realised it was like the vagina and womb

of the earth: the old winter mother receiving and holding the spirits of

the dead, maybe from there enabling their birth into another dimension:

a place of death and rebirth and for shamanic initiation - a different

kind of death and rebirth. I was finding myself so completely at one

with the earth that I became the earth, so being inside the long barrow

was like being inside my own body, the ancient ancestral body of the

Winter Hag. There was nothing to fear, for how could I fear my own body,

how could I fear the body of the Great Mother?

The Tibetan Dzog Chen teachings seemed so familiar that I thought the

Neolithic belief-system of these islands could have come from the same

roots as that of the pre-Buddhist Bon religion of Tibet. Here too

perhaps the bones of the ancestors had been excarnated, used as sacred

objects, put in the long barrow and taken out for ceremonies; femurs

used for thigh-bone trumpets, skulls used as bowls or skinned over to

make drums. This was the winter, the night and the dark, and outside

were the black skies and stars. And this was my reality now.

There were not so many visitors to the long barrow in those days, at

least not in the winter dark. A few groups turned up in the evening,

surprised to find me there, but then I would have the place to myself. I

half-slept, half-dreamed and had things that were more visions than

dreams. I saw a group of elders dressed in white sitting in a circle

chanting, with a line of light from the outside shining along the

‘vagina’ of the barrow to the centre of their circle. I was close to

those ancestors, those ancient people who gathered for the ceremonies of

the night, who had called out to me all those years before.

I had a sleeping-bag and rug and wore lots of clothes, by now used to

being outdoors. Aware of the cold I was learning to wrap it around me

like a blanket so the essential ‘me’ stayed warm on the inside and

wasn’t cold. It was a form of practice. I had little to eat or drink, so

these nights out became like vision quests. I was in an altered state of

reality anyway (no drugs!) but this was becoming my norm.

In the mornings I would walk to the top of the hill where the ancient

Ridgeway Path meets the A4, because in those days there was one of my

‘best caffs in Britain’. It was a truck-driver's cafe where they would

stay over-night, so was open early for breakfast and late into the

evening. They didn’t seem to mind if I sat there for hours drinking tea,

thawing out, coming into the day, before walking back to Avebury and, if

I was going home, the Swindon bus and the train back to London. I

returned often to Avebury and other places in Wiltshire and Berkshire

during this time of discovery.

It was very strange for my daughters who didn’t understand at all what

was going on. I didn’t myself, though it seemed everything I was doing

just had to be. I had no way of putting it into words or communicating

it to them. I’d been a brilliant mother to babies and little children,

maybe because I had had a mother until I was two, but I’d had no role

model for motherhood of teenagers and hadn’t learnt the right

communication skills. To them I was becoming a different person, but I

felt that at last I was becoming the real me. It was a very difficult

time and the intervening years haven’t made it any easier. That was one

very sad aspect my new life, even though I was making friends with

people who understood without my having to explain...

...1982 came. Once again I did the Arts Council application for our

Guarantee Against Loss. We had to give them the schedule of all we

planned to do in the forthcoming year, and then stick to it, even if we

wanted to go off in a different direction. This time we were turned

down. On one level it was totally shattering, as the money had not only

provided all the costs for our performance work, but had paid to keep

our vehicles on the road and a percentage of our telephone and

electricity bills. But on another level, although it scared me, it also

freed me from being trapped in my working partnership with Bruce. I was

no longer tied to a year-long schedule of work with him. I was free.

I organised a lovely exhibition with a group of artists at a small

gallery in Brighton and in preparation spent some nights out on the

Downs and in the great earthwork of Chanctonbury Rings, which was

covered by a huge canopy of trees. It was a terrible shock to return

some years later to find nearly all of them had fallen in that same wind

of 1987 which brought down the trees at Waylands Smithy, but there

again, it probably looked more as it had in the days when it had been

built. It had been utterly magic there in the dark, under that

whispering canopy; a memory I shall never forget.

While we were living in London, I had been strongly pulled to visit the

Callanish Stones on the Isle of Lewis in the Western Isles of Scotland,

but we had never gone. In 1980 and ‘81 a group of artists and

photographers we knew went there and stayed some weeks each time. They

had tried to persuade us to join them, but some of their strange stories

had put us off and in hindsight I am very glad I didn’t go then; with

Bruce.

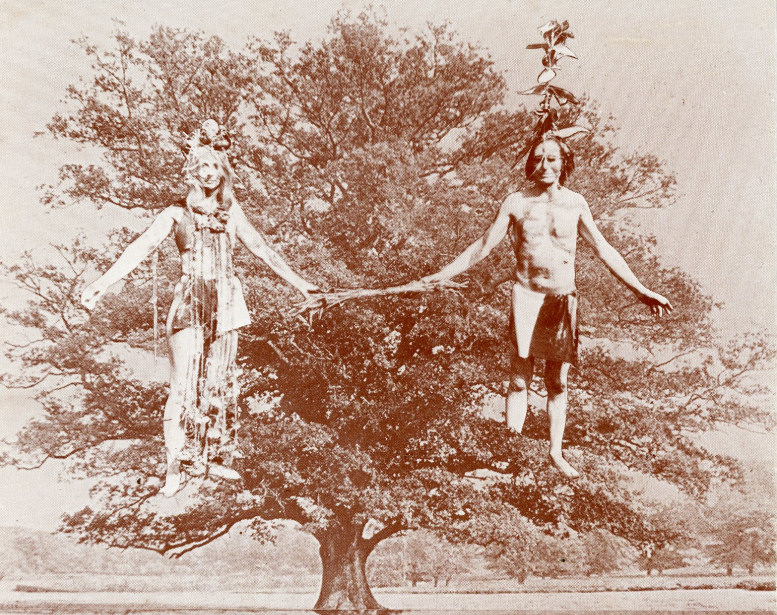

One year, when they returned, I was sitting with Saffron in a tent at

the ‘Faerie Faire’ in Norfolk when one of the artists – Keith Payne –

called by and told us of a mountain which could be seen from the

Callanish stones: ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ resembled the profile of a

sleeping woman and every 19 years, at the major southerly lunar

standstill, the low rising moon emerges re-born from her body (picture

above). Hearing

about this affected me deeply and from that moment, not only Callanish,

but this sleeping mountain, began to fill my awareness, calling me

strongly to go to them.

In 1982 Keith and the writer John Sharkey were about to set off on a

journey up the whole of the Outer Hebrides, visiting all the ancient

sites in the Islands, writing a book to be called ‘The Road Through The

Isles’ (Wildwood 1986). A whole group of people including Monica Sjoo,

and Lynne Wood who had been part of the ‘80/’81 group, were going to

meet up with them at Callanish for the Summer Solstice. It seemed as

though this was the time I must go to the Islands and the mountain: the

call was so strong I could no longer resist. However, it was so

overpowering I felt I couldn’t just pop up there like a tourist,

believing this to be the greatest pilgrimage of my life. I heard of a

concept, originally Lynne’s, which seemed to be the journey I must make.

I was by now perceiving the whole of Britain as the body of a great

creation ancestress lying in the sea; the body of the great goddess, the

body of Albion.

It was thought that certain key sites right up her body - from toe-tip

to brow - corresponded to specific places in one’s own body. I felt them

to be not so much chakras but the ‘places’ in a Dzog Chen purification

practice I’d been doing. It all rang totally true and the form of the

pilgrimage I must make to finally reach Callanish at the Brow of

Britain. I needed journeys to have a shape, structure and purpose, and

this was perfect, absolutely what I must do. I would rise up through

these sites in the body of the land, carry out the purification practice

at each and in the places in my own body. I would link them into a line

of light and carry it to Callanish. I was going to the Islands at

last...

'The Gypsy Switch

and other Ritual Journeys', with a foreword by Jeremy Deller, is

available from

www.antennapublications.org.uk (Paypal),

http://www.jill-smith.co.uk/books/

or Amazon. See 'interviews' for a 2015 interview with Jill Smith.

|