|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

The Tree of Thought: The Art of Kate Walters Penny Florence

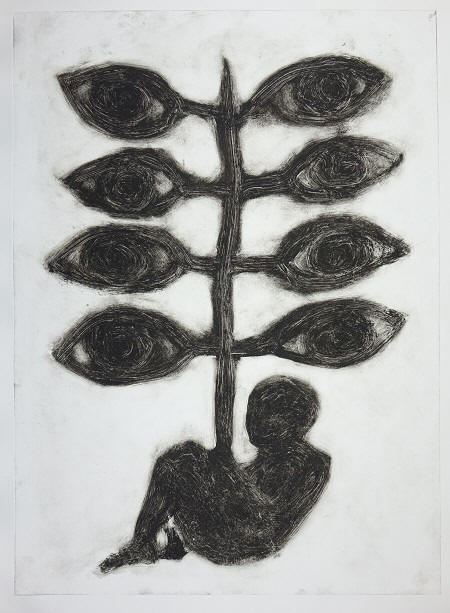

Embodied thought addresses the kind of understanding that bypasses spoken or written language because it is deeper. Precisely because it embodies rather than explains or narrates, it is not didactic; Walters never preaches. There is, nonetheless, a powerful and consistent message. It concerns the big questions: what does it mean to be fully human; what is our place in the natural world; where are we going; questions that echo Gauguin’s great philosophical work, D’où venons-nous, Que sommes-nous, Où allons-nous? But, unlike Gauguin, the work does not so much pose questions as feel its way towards articulating the mysteriousness of being. This is a Shamanic understanding of what many of the ancient religions variously call the Path or the Way – and Walters is a fully initiated Shaman. This is not a casual or loose similarity, but rather the long-term commitment that underpins her art. So what is this Shamanic terrain? It is paradoxical, because it is fully aware, yet indirectly evoked. If you compare Child with Plant Wand (above right) and Buds with Babies, the eye-leaves of the first appear to be the seed-children of the second, who resemble the child holding the plant. These eyes suggest insight as much as sight, awareness and receptiveness to the cycle of rebirth, to movement out and movement in, like breathing. It’s an effect that reminds me of what Maleno Barretto said of the intrepid Margaret Mee (both botanical artists), ‘She seems to be inside the plant’¹. This suggests that art does not distinguish us from Nature, but rather is integral to it. Many of us who have known individual animals well understand the absurdity of the idea that they don’t think. It’s the result of projecting our ways of thinking onto creatures whose experience of the world is different.

Perhaps we might call this capacity to see into the life of things ‘Natural Intelligence’, not in opposition to ‘Artificial Intelligence’, but as a complement. ‘Human Intelligence’ is only one form. Mee always worked entirely from living plants, usually in their natural setting and including their habitat, unlike conventional botanical illustrators. In this way, she shows that that they are integral to their environment, an inseparable part of it. To capture the enigmatic Moonflower (Selenicereus wittii), which blooms once and night and then dies, she balanced half the night astride a narrow canoe. She risked herself alone with nature in order to convey the living energy of an organism in its habitat. And it is a risk; like her, Walters risks herself. The result is demanding work that rewards the concentrated looking of open awareness. Truly look at the works in this show and you will see that living energy, a life-force that unites everything that lives and breathes; for, as Simryn Gill, another artist admired by Walters, said, “If the botanical world falters, so do we.”³ Our ability to breathe has evolved in exact synergy with theirs. It 3 is an understanding that demands action and restraint from harm, a thoughtfulness about balance and care. In this it is political; in Gill’s case, against colonial exploitation; in Walters’, in support of Extinction Rebellion (XR) and taking personal responsibility.⁴ At the same time, the works are underpinned by a structural precision belied by their fluidity and softness. This aspect of the work is evidenced in the approaches of two other artists Walters admires, Christine Ödlund and David Thorpe. Both explore geometry and growth.

The image is not materially differentiated from its surround; it’s a matter of degree and, more subtly, of construction, as in the figure-ground instability of Seeing Tree or Storm, World Tree with Cocooned Infants and Untitled. Plant, tree, animal, bird and human life all materialise in these works in the gap that is ambiguity, all part of the same miraculous planetary process. The oils foreground the kinds of emergence to which the medium is so perfectly suited. Colour, marks (both ends of the brush) and a fragile symmetry create a textural and layered becoming in which the animals both support and merge into the human and plant forms, from birth to dissolution. From a distance, the palette and composition evoke C17th Dutch still life masters; ‘still’ life here meaning ‘always’, not ‘motionless’. They form a Tree of Thought. For anyone who thinks they know more than this planetary tree, I offer this couplet from William Blake’s Auguries of Innocence: The Bat that flits at close of Eve Has left the Brain that won’t believe

|

|

1. Botanical Art & Artists.com About

Margaret Mee (1909-1988) (Malu De Martino on Vimeo.) Walters has

recently looked at the work and thought of Mee, along with Simryn Gill

and the filmmaker and gardener, Derek Jarman.

Kate Walters 'Notes in the Garden', Tremenheere 7.9.19 – 2.10.19

©Penny Florence 18.9.19 |

Kate

Walters’ art speaks clearly. Yet because it is visceral, communicating

to our bodies first, it can be easy to underestimate the quality of

thought it embodies.

Kate

Walters’ art speaks clearly. Yet because it is visceral, communicating

to our bodies first, it can be easy to underestimate the quality of

thought it embodies.  But

plants? There is increasing scientific evidence that plants, especially

trees, do indeed think. The interdependence of trees, for example, is

such that they form something very like a community. Theirs is a

collectivity based on communication. It is extensive and applies to the

entire tree: apparently their more widely known capacity to warn each

other of insect attack through the release of hormones above ground, and

to take defensive action, is complemented underground, partly through

the intermediary of fungi. Fungi are neither plant nor animal, but a

form of life in between.²

But

plants? There is increasing scientific evidence that plants, especially

trees, do indeed think. The interdependence of trees, for example, is

such that they form something very like a community. Theirs is a

collectivity based on communication. It is extensive and applies to the

entire tree: apparently their more widely known capacity to warn each

other of insect attack through the release of hormones above ground, and

to take defensive action, is complemented underground, partly through

the intermediary of fungi. Fungi are neither plant nor animal, but a

form of life in between.² This

sense of co-emergence is conveyed not only through form, but also

through technique. There are four methods in this show: watercolour,

monotype, spit bite etchings, or a combination; and oil. Take for

example Kate’s three spit bite etchings:

This

sense of co-emergence is conveyed not only through form, but also

through technique. There are four methods in this show: watercolour,

monotype, spit bite etchings, or a combination; and oil. Take for

example Kate’s three spit bite etchings: