|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

The Legacy of Susan Cooper’s Greenwitch Matthew-Robert Hughes

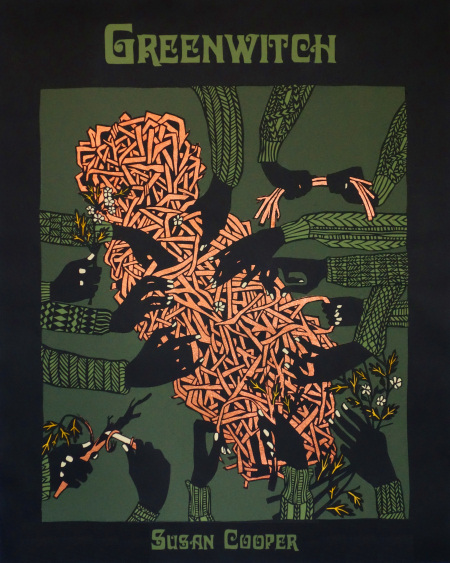

"There was a great mess of little twigs and leaves, hawthorn leaves and rowan. And everywhere the great smell of the sea." In 1974, twelve year old Jane Drew was invited by Mrs Penhallow, a friend of her Great Uncle Merry, to take part in a Cornish folk tradition. This ceremony was celebrated around the Pagan Festival of Beltane in the imagined Cornish coastal town Trewissick. What Jane experienced that night was a local living folk tradition, one of many that are celebrated across the British islands today. ‘“Ef you fancy comin’ to the makin’ tonight m’ dear? You’m welcome.” Jane blinked at her. “The Making?” “The makin' of the Greenwitch.”’ The Making of the Greenwitch took all night and the work was only ever done by women. This creative ritual ended when the Fisherman returned from sea in the early hours of the morning.

Hours passed, and the women worked steadily throughout the night, singing and laughing. Jane drifted in and out of sleep, but every time she awoke the form had changed. Hazel for the frame, Rowan for a head, and a body made of the Hawthorne. The Greenwitch was starting to appear. It frightened Jane, but it was strangely hypnotic. When the work was done, the women sat by the fire eating sandwiches and drinking tea. Some of them broke away from the group and headed forward to the Greenwitch, making silly wishes for rich husbands or handsome lovers, laughing and giggling. The silent image of the Greenwitch held more power than any creature or thing that Jane had ever seen. It was outside of time, ageless, belonging neither to the Light or the Dark. It belonged to the The Wild Magic of the land, sea and skies. Jane gazed further at Its image and felt its loneliness with pity. Grabbing the hawthorn like the other women had done, Jane made a selfless wish for the Greenwitch to be happy. A sound came from the sea, lights flashing. The first fishermen were coming home. The cawing of gulls and the smell of fresh fish came up from the sea. Up from the beaches came the fishermen, up to the fires of Kemare Head, calling cheerfully to the women and warming their hands around the fire. The Greenwitch stood still and silent, in awe of the new arrivals. The men started to gather in a group around the Greenwitch, holding branches, laughing and making wishes. ‘“The Men will put the Greenwitch to Cliff,”’ said Mrs Penhallow. This act was done for luck, for good fishing and harvest. The men moved closer together, lifting the hulking body of the Greenwitch. The sun began to rise and the men pushed the body over the cliff’s edge. Flung into the air, down to the sea to drown, helped by the stones placed inside its body. Jane looked down over the cliffs of Kemare Head as the sea washed against the rocks. Only a few twigs of Hawthorne remained on the surface. This is a small event that happens in Greenwitch (1974) the third book of Susan Cooper’s Dark is Rising sequence, but it is one that has always stuck in my mind. The Dark is Rising is a series of five children's books centred around five magical and ordinary children set against the backdrop of Cornwall, Wales and Buckinghamshire, with a blending of Arthurian Legend and English folklore and traditions.

Jane Drew’s character was written originally in the shadow of the capers and japes of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five. She originally appeared along with her siblings in 1965 in the first book Under Sea and Over Stone, also set in Trewissick (based on the coastal village of Mevagissey where Cooper spent her childhood holidays). Jane’s character at first appears to be gentle and often rather flat, always fussing over her younger sibling Barnaby. But in Greenwitch, it is Jane who is the key to defeating the Dark, over and above those who have the knowledge, skill and magic. This is what sets this book apart from the others in the Dark is Rising sequence. She does this by showing the act of compassion towards the Greenwitch, which begins with her selfless wish for it be happy at the making with women of the village. This act allows Jane as a non-magical character to have her own magical awakening, later experienced through dreams in which she speaks with a living form of the Greenwitch. The reason I feel connected to this event, is its highlighting of folk customs and traditions, told through the making of the Greenwitch by the local women of Trewissick. The act itself is its own form of folk magic. The gathering of women inclines towards that of a coven. There is the making of a magical totem imbued with intention from the songs and chants, a part of women’s lore and knowledge that has been passed down so it is not lost. Throughout The Dark is Rising sequence there are acts of magic, spells, battles between the Light and Dark, Arthurian legends, magical objects and weapons of power, but it is in this gesture that the wild and folk magic seems very familiar to me. It is how the locals and women of the village of Trewissick who continue these traditions tie The Dark is Rising to the realm of the real. It reminds me of the The Obby Oss in Padstow, Lewes bonfire, or the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance, and the many other strange and weird customs held across our island. It is within our own folk traditions that we can understand our place in the world and our connection to nature. The people who are practising these traditions and customs today are helping to preserve and keep the magic of our island alive, rather than through the non-living restriction of objects and regulations in museums and institutions. Our folklore is a visual and oral history, our own social history, anarchy and a celebration of the seasons.

We learn that the Greenwitch is sent as an offering to Tethys, the goddess of the great deep ocean and seas. In a meeting with Tethys, two other characters Will Stanton and Meriman (The Old ones) the goddess talks of her own truth, myth, legend and hints at her forgotten meaning. In a drawing made by Jane’s brother Barnaby of Trewissick Bay, gifted by Meriman to Tethys, she sees the name The White Lady written on one of the boats. ‘“So the fisherman do not forget. Even after so long, some do not forget.”’ In this we are reminded to guard against the loss of the origins of our folk traditions, customs and superstitions, the oldest of our religions and the power of magic and imagination. Women’s Lore is becoming lost, along with some traditions and customs that connect us to our lands. But there is a propagation of British folklore for a new generation and it is happening through the celebration and documentation of folk festivals and traditions, stories both written and oral and through the magic of art making. Stories like Greenwitch or The Weirdstone Trilogy by Alan Garner, show the power of children's books. Events like the making of the Greenwitch linger on in the adult mind, helping through life in a subconscious way, to keep traditions, myths and the magic of our land alive and living.

Essay written for 'Waking the Witch' touring exhibition (2018-2019 - see 'exhibitions'). Catalogue available from www.legionprojects.com. Greenwitch illustration by Maren Salomon 2018. Seawitch on Llangrannog beach by Daisy Murray (aged 9). 10.12.19 |

|

|

When

Jane arrived at

When

Jane arrived at  The

five Children are Will Stanton, who has a magical awakening on his 11th

birthday when it is revealed to him that is the last of the old ones;

The

five Children are Will Stanton, who has a magical awakening on his 11th

birthday when it is revealed to him that is the last of the old ones;

Even

though the Greenwitch ceremony witnessed by Jane is fictional, the power

of Cooper’s imagination helps us to celebrate and understand the

connections and origins of our own folkloric traditions. The Greenwitch

is offered to the sea, but it is Jane who in her dreams now travels to

the underworld of the seas and speaks to the Greenwitch and sees the

Wild Magic of nature.

Even

though the Greenwitch ceremony witnessed by Jane is fictional, the power

of Cooper’s imagination helps us to celebrate and understand the

connections and origins of our own folkloric traditions. The Greenwitch

is offered to the sea, but it is Jane who in her dreams now travels to

the underworld of the seas and speaks to the Greenwitch and sees the

Wild Magic of nature.