|

Gathering

Martin Holman responds to 'Gathering' at Gray's Wharf,

Penryn, 28.5.21 - 13.6.21

The word ‘Gathering’ is an unlikely provocation. In normal times a

gathering is a common event, often with specific intentions, a family

celebration maybe or an assembly with religious or political purposes.

And it is an occasion usually looked forward to with pleasure.

But that is in normal times. In the inescapable context of the global

health pandemic, however, the invitation for people and objects to come

together in one place and share an experience collectively is greeted

with alarm, certainly with apprehension. After all, for months just

about every inter-personal activity outside the family has been

restricted by a non-coercive democratic state exercising the force of

law. Only subversives challenge that state of affairs.

The people behind this exhibition with a title that makes the heart race

might fit the description of a subversive, at least generically. They

are, after all, artists, members of a community of habitual social

inquisitors in any context at any time. The ten participating artists,

all based in west Cornwall, responded to the invitation from two of

their number, Verity Birt and Jonathan Michael Ray, to ‘explore the act

of gathering and its value today after a year of travel restrictions and

social isolation’. Art does not thrive in a bubble or what is known in

COVID times as a 'minimised risk environment'. So, the opening of this

show’s fortnight run in Penryn marked the arrival of that point on the

government’s road map out of lockdown when mixing in England was

cautiously relaxed. Non-commercial galleries had re-opened, and guests

needed bring nothing but themselves and being prepared to interrogate.

And, of course, they needed a face covering.

The organisers provided the nourishment. Not only did the show succeed

in hydrating the spirit after a drought in the galleries of the

south-west, 'Gathering' also wove its theme in and around the gallery

through individual works laid out with care and intelligence.

Relationships arose in formal associations as well as via cultural

coincidences, with the area’s folkloric traditions a common allusion.

Each artist made a single contribution so that the works felt in touch

with the time and in touch with each other. Each piece was an offering

in mind and body to the visitor who could walk away physically refreshed

and mentally reanimated.

Ilker Cinarel: Honesty Box (detail)

Ilker Cinarel’s 'Honesty Box' captured the theme directly with a wooden

stall of the type encountered on roadsides and at farm gates, stocked

with fresh produce on sale to every passer-by. When much art reflects

the cynicism rife in the commodification of increasing amounts of

contemporary life, Cinarel latches on to the trust that holds society

together, a quality that has been affirmed, tried and tested (but not

tracked) during the era of the virus. Unlike the sober reality of farm

shops, Cinarel’s stock lines ran beyond the culinary staples of

cucumbers, potatoes, courgettes and local home-made jam. Those rural

essentials were all there but so too were items that pointed hopefully

towards future, undistanced liaisons: artist-rolled cigarettes,

exotically branded condoms and a selection of bottled amyl nitrates.

Where does a stall with such good-natured intention and festive

demeanour deserve to be sited? Fronted by the eponymous honesty box

itself, painted pink and embellished with glitter and disco balls, it

should establish a new norm of pop-up retail. This was remote selling at

its most affable, with discretion not entirely assured.

Matching Cinarel’s warmth and humour was Georgia Gendall who foresaw

popular anticipation of the return to outdoor pastimes by proposing

participation in the 'Penryn Worm Charming Championship'. ‘Worm

charming’ is a recognised competitive sport – at least in east Texas,

according to Wikipedia. The same source also divulges that homo sapiens

is not the only species to ‘grunt’ or ‘fiddle’ the worm. Gulls do it and

even wood turtles stamp their feet while doing it. But among humans the

skill is at risk of dying: that creative being has developed easier and

more industrial methods of coaxing earthworms destined for the

fisherman’s hook out of the ground. Nonetheless, festivals in Devon and

Canada attest to the survival of the ‘stob’ and ‘rooping iron’ to

‘twang’ the soil, if only in the cause of entertainment. Penryn can be

added to the roll call because Gendell was promoting a gathering of her

own, scheduled for a rural location a fortnight after the show’s

closure. This thoughtful gesture to keep the communal spirit glowing

projected the visitor’s widening horizons towards another place in the

near future to banish the worst of lockdown woe into memory. The artist

connected the visitor with the event through a QR code to scan: a

virtual space tacked on to the real one of the gallery. The incentive?

If the prospect of gathering was not enough, the glazed ceramic objects

in the gallery itself, palm-sized and worm-like, were offered as

trophies on their slow approach to the winning competitors.

Georgia

Gendall: Penryn Worm Charming Championships (foreground) Simon

Bayliss: WS Graham Bounce Mix (background)

Both Cinarel and Gendall anticipate directly people getting together;

the presence of unseen others is clearly implied by their work, their

absence only temporary but almost palpably sensed. The same is felt in

Simon Bayliss’s installation, which is also opened up by QR code from a

wall of posters into an additional space accessed through headphones.

And as with the previous two artists, whose work is wide-ranging in

media and embraces the absurd and the communal, Bayliss’s mix of print

and music here reflected his established practice, one which also

extends into pottery and performance. All the contributions to the show

can be considered typical of what the artists do or, more accurately,

the idioms they engage with as part of several parallel and linked

strands that make up their careers. With Bayliss, that spread of

activity is the material that builds bridges between ways of making. A

common feature is the word, spoken, written and sung, as substitute for,

and in juxtaposition with, the image. The textural variety is conceptual

and material, from bulky clay to spikey, linear soundscapes in a redrawn

artfulness. His choice of mixing W S Graham, the Scottish-born poet who

settled in St Ives, with modern dance music tracks effectively recasts

the context in which the poet’s work is usually encountered. Bayliss

also draws on a creative figure from the recent past who complements

this artist’s own co-operative spirit. Graham’s output flowed between

idioms, seeking to make bridges between poetry and painting, for

instance.

Admired by Dylan Thomas and T.S. Eliot, Graham was a point of contact

between neo-Romantic and modernist currents in mid-century British art.

On one occasion Graham asked fellow diners at the Gurnard’s Head in

Zennor to mimic the sound of a raging gale. Indeed, metaphors for

weather often drive his narrative poetry, which gains momentum like the

onset of a storm at sea, then slows the way a storm subsides. For 'W S

Graham Bounce Mix', Bayliss punctuates the mixed tape of dance music

tracks with the words of Graham’s poems which he speaks against a

background of sound, like the ghost of Graham’s impromptu choir. One

poem is titled ‘Five Visitors to Madron’, a COVID bubble ahead of its

time. In ‘Two Poems on Zennor Hill’ Graham exhibited an interest in

wordsmithing as rich as contemporary DJs’ explorations of fresh sounds

and mixes. And location as a subject was as important to Graham as it

seems to be to Bayliss, although with different outcomes. For Bayliss

the spiritually unifying urban arena of the techno dancefloor is as

energising as the wilderness of the Penwithian moors, heritage of stone

quoits and turbulence of air, land and sea.

Music and language are about communication. Graham enjoyed being

‘assailed by our acquaintances and a friend here and there’ among St

Ives artists once he moved to Cornwall in his twenties; he thrived in

the company of others and, one senses, he would have enjoyed the

dynamism and passion of the rave scene. For perhaps his most famous

work, 'The Nightfishing' (1955), a night in a herring boat out on the

North Sea, Graham made use of the ancient musical rhythms in bardic

poetry. At any time, he revelled in a sea of words, in rackety phrases

and concatenating combinations of adjectives. Above all he primed

metaphors where the appearance of reality is turned with craftsmanship

into the sweeping arc of the imagination.

As in Verity Birt’s 'Brackish Rite (votive offerings to the Penryn

River)' which manifests itself in the gallery as a coracle beached on

the gallery floor. Long coloured ribbons tied around the wildflower

bouquet sprouting at the apex of willow rods arching over the boat’s

interior, stream out over the concrete floor in imitation of ripples on

water that have caught the light. Birt constructed the single-person

vessel using traditional techniques so that, as with Gendall and her

worming event, the work assumed an element of preservationist zeal. As

an object out of place, the coracle resonated with its temporary siting

in an intriguing fashion that amplified its presence from dark-coloured

woven basket into a single relic snatched from its context to stand for

an entire cultural system in a museum.

At first it appeared beautifully

melancholic as the gift brought to the party and soon abandoned. Because

mystery gathered round its presence, its components percolated into

several consecutive narratives before brewing into its actual purpose,

prompted by the reference in its title, to the ‘Brackish rite’ itself,

another performance planned for the last day of the show at the point on

the Penryn river, where fresh water meets the sea.

Verity Birt: Brackish Rite (votive offerings to the

Penryn River) (detail)

Birt’s contribution fulfilled two briefs running through the show. The

first spanned definitions of gathering, to which Birt applied the ritual

significance. The second related to a pre-existing text available to

visitors in a bespoke edition at the entrance. This risographed booklet

reproduced the essay that offered a redefinition of human evolution,

first published in 1986 by the American master of speculative fiction,

Ursula K. Le Guin. Called ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, this

story supposes that before the human species made sticks into swords to

hunt with and kill, ‘the tool that forces energy outward’, ‘we made the

tool that brings energy home’. Thus, the ancient ancestors of today’s

populations first of all invented the container, a constructive tool

that brought beneficial items to the home or the shrine, that is, the

setting for whatever is sacred. The forerunner of the modern utilitarian

carrier is exalted, in Le Guin’s words, as ‘the bag of stars’.

Le Guin’s proposition had most relevance to Birt. Visitors were invited

to model votive objects of their own with the materials that the artist

provided. They were then asked to consign their creations to the boat’s

interior as it sat in the gallery like a large basket in order for them

to be incorporated into the rite performed on the river when the coracle

set out on the water. But Le Guin’s text has a wider meaning: it

formulates a metaphor for the act of storytelling. Not only is the

pursuit of narrative integral to the critical process of interpretation

of art works, it is also the product of imagination, the faculty at the

core of being human. Le Guin meditates on a vision of the evolutionary

sequence that places collective holding and sharing before aggressive

dominance. Storytelling is a communal act of sharing. As such it sits

well within this exhibition; to a lesser or greater degree, all artists

figure out different realities through making, paralleling Le Guin whose

constructive medium was writing.

Lucy Stein:

Becoming Boscawen Un (detail)

The figures, palette and compressed space of 'Becoming Boscawen Un'

negotiates several mythic storylines consecutively. The large-scale

painting by Lucy Stein relates to her long-standing interest in the

sacred sites of West Cornwall and their ancient origins. Stein also

works with ceramics, film and performance in a manner that relates her

sources to the present and to contemporary artistic and political

themes. Most clearly cited in the present work is the so-called

primitivism in Picasso’s images from that period of his career around

1907 when he revolutionised western painting by discarding traditions of

beauty and compositional unity and importing conventions from Asian and

African art, that is, from cultures then regarded as colonised and

inferior. Within that language Stein presents a confrontation with

assured but only half-recognised female figures who look confidently out

of the picture’s space and into the gallery, namely the visitor’s

domain. The congested atmosphere is almost incantatory; bodies weave in

and around the interior space as if summoned by an unseen narrator.

Stein draws upon Penwith’s pagan heritage of matriarchal religion in

which goddesses of the moon, fertility, the setting sun were worshipped.

Boscawen-un is a Bronze Age stone circle near the town of St Buryan

associated with the bard, or storytelling tradition in Cornwall, and

mentioned as an arena for poetry in early medieval Welsh texts. On its

arrival Christianity subsumed these legends into its own hierarchy of

the virtuous, merging goddesses with its saints in a celestial order

dominated by a single godhead revealed as three divine personalities,

two of which are assumed male (and the third might be) below whom ranks

its own Mother Goddess figure, Mary, the mother of Jesus. Not that

Cornish regard for the pagan past was entirely overturned; rather, its

beliefs were concretised in myths about the origins of standing stones,

for instance, and folklore about the transgressive force attached to

witches and the occult.

The gathering depicted by Jonathan Michael Ray is, by its title, a 'Holy

Reunion'. Since the time of Rembrandt and Hals, reunions have been

commemorated by group portrayals, the arrangement of which grew steadily

more formalised once the medium of depiction was assumed by photography.

The Victorians perfected the stiff poses of unrelaxed faces turned to

the front, united in common purpose; and it went without saying in those

days that the faces were most often male. The assembly in Ray’s

composition, by contrast, conveys an atmosphere of doubt or urgent

confusion. Do the participants know why they are gathered in that place?

Or, having accepted the invitation, have they missed the point of it?

Heads look this way and that, and sightlines cross. They look everywhere

except upwards to the pair of feet just visible at the image’s topmost

edge. The detail is easily missed but appears significant. Do those feet

precipitate a landing or the owner’s ascent, or a third possibility

which is the execution of a truly spectacular feat of self-levitation

and hover to be followed by a return to earth?

Jonathan Michael

Ray: Holy Reunion (detail)

Ray’s route to possible meanings assumes the language of ecclesiastical

stained or coloured glass. Every part of the composition is anchored

into place by lead seams, an historicism that arrests the frisson of

alarm in the viewer of early summer 2021 who is by now drilled into the

discipline of two-metre distancing. The immediate association of the

image is with Biblical illustration, the holy communion of souls, of

hosts in Heaven and the community of saints. But that does quite fulfill

the possibilities in this case, in spite of the proliferation of

halo-like headwear among the men. The stained-glass medium has acquired

increasingly secular uses over the centuries and perhaps is most often

seen, religious buildings aside, in homes and offices. Ray rescues old

glass; he sources examples online that come from all types of place but

most comes from chapels and churches. He acquires the glass as raw

material, giving it new purposes by mixing fragments in need of

restoration into a story of his own. The potential is obvious and the

directions it can take, formally and conceptually, are numerous even

within the limitations that so many superannuated saint figures create.

The audience’s collective assumptions might tend towards the obvious

interpretation of a faith-based narrative – and Ray, interestingly,

applies the adjective ‘holy’ to the title. But even that word has gained

a richness of usage that is not entirely devotional, as Batman’s Robin

can attest. So Ray responds with a question to the viewer about how far

assumptions can be trusted.

Narrative is not exempt from any part of this exhibition; no artwork

relies entirely on non-objective attributes of line, form, colour, space

and time. The wall-mounted works by Tom Sewell and Dan Howard Birt

gather elements into assembled compositions in rebus fashion to unlock

narratives of meaning to a visitor investing time to achieve an

interpretation. Sewell’s 'Sunrise ’21 (Deep Field)' is the most

cohesive. In a sense, it resembles a traveller’s record of place and

experience triggered by tokens. The type of transit, however, is left

sufficiently open within the work itself for an onlooker to fill gaps.

(The free gallery guide offers the artist’s viewpoint although

compliance is not mandatory.) This work picks up from Birt’s coracle

situated next to it, since both call upon associations with folk art as

the genre chosen by highly skilled people wishing to express their

creative urges, for whatever reason, outside artistic conventions. The

diaristic feel of Sewell’s collage of disparate finds in the landscape,

from shoreline driftwood, rope, shells and stones to pewter objects and

an onion, is pulled together with graphic clarity on a rectangle of

meshed fencing placed over a sky-blue ground applied to the wall. The

mesh is stretched between willow poles: the imitation of painting, the

historic portal to illusion, might be coincidental, just as the

suggestion of a page seems apt, for literary overtones exist here.

As they do in Howard Birt polyptych of

painted supports – canvas, calico and wood panel: a brief history of

painting. The surfaces carry emblems and lettering, from the largest

which spells ‘H’m’ to a side column of legible phrases derived from

writings by artists and poets to which the gallery guide provides a

quick key. It mentions Graham Sutherland writing about Picasso, a line

from T.S. Eliot’s stream-of-conscious early poetry, and an expression

coined by the Welsh priest and poet R.M. Thomas. Finally, Giotto is the

source of flaming rock on the big canvas and, conceivably, the title,

'Trial by Fire'. Actually, the work brings to mind the recurrent history

of making any painting; the deliberation and doubt, the borrowings

(unattributed offerings?) and pilfering from other artists that go into

the creative ‘mulch’ that Howard Birt refers to in a statement. From

that compost springs another picture in the author’s inimitable style,

one that balances precariously between adequacy and, as epitomised by

the allusion to Eliot’s arguably love-struck J. Alfred Prufrock, fear,

failure and the false start, even before it goes out into the world. As

Howard Birt implies, every artwork is a gathering in itself, a socially

undistanced cross-referencing of influences and ideas. At its centre is

hesitancy, if that is the condition suggested by the largest element in

the painting, the phrase ‘H’m’, ensconced in a burnished oval where, in

certain religious imagery, the name of God might appear like writing on

the wall.

(On wall) Work by Tom Sewell and Dan Howard-Birt, and

(on floor) Steven Claydon

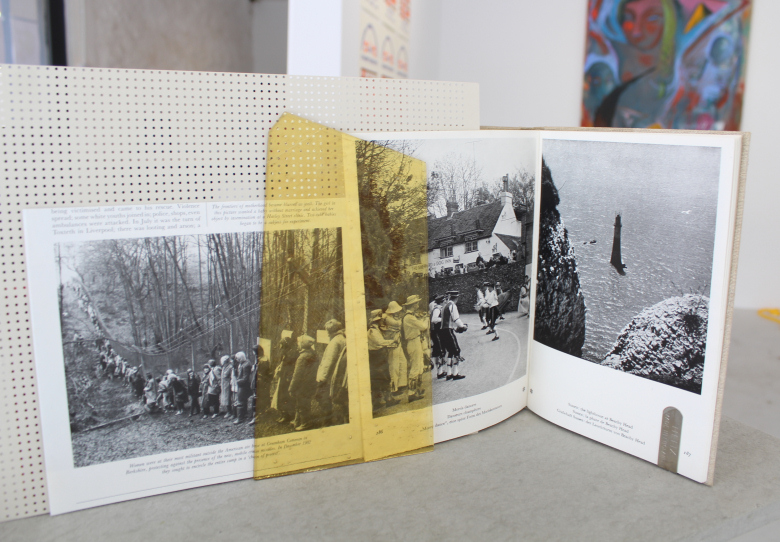

Every part of Abigail Reynolds’s

contribution seems to have had a life elsewhere before being brought

into the conceptual space of 'The Maidens'. Put differently, the piece

is a composite of objects manufactured by others with no thought of

being in this artwork. Several decades ago, such a manoeuvre by the

artist would have been transgressive; further back in the last century,

it would have been deemed unacceptable behaviour. The world has moved on

and art with it so that Reynolds’s method is as mainstream as the

current heterogeneous art world can manage. That opinion does not

express scepticism because every element, imported though it is, is

integral to this artwork’s being. It is another form of repurposing.

From first encounter the collection of geometric shapes – books,

tabletop, table stand; two interconnected rectangular frames, a

perforated metal grille and the neat that keeps the open pages of one

book from folding shut – emits significance that requires investigation.

Firstly, the assemblage feels modern, in that mid-last century way of

Isokon Flats architecture and Mies’s furniture. Then that sensation

carries on to the rectangular reproductions in the book pages opened to

view; they are not colour photographs but elderly monochrome. The books

themselves are not new but date back at least forty years. Yet the

images the artist directs attention the viewer to are, in some way, what

is now called ‘iconic’.

Abigail Reynolds: The Maidens (detail)

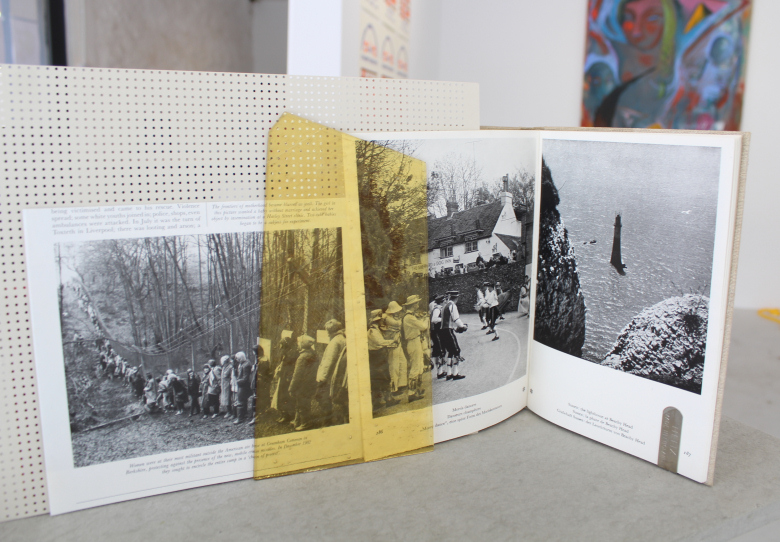

They depict gatherings of one sort or

another. Reading from the left, as people tend to do, the anoraked and

booted women lining a tall perimeter fence instantly mean Greenham

Common to viewers of a certain age. The location defined an era of

division in British history. The next image has morris men dancing for

an audience which sits atop a wall fronting a pub, a thatched building

with a steep gable below which its name plus ‘inn’ is legible, all

symbolic details of an image England has cultivated about its stability

- traditions that have leeched into a nation’s vision of itself of

settled social structures, leavened by innocent good humour and

untainted by dissent. Reynolds also gives exposure to the cover of the

book in which this picture appears. Round the back, blocked in red

capitals on the solid grey cloth of its stout binding, is one word,

‘England’, spelled out in red characters with Biblical assurance.

Next to the morris men, on the facing page, is the lighthouse at Beachy

Head. It may or may not be part of this work but an accident of

publishing that could not be hidden. To assess this possibility is also

to realise how politicised England’s image of itself has become. The

lighthouse can be interpreted as another symbol of island identity, the

stoic guardian of life and shore alert to threats that come from across

the sea, from ‘out there’. Moreover, that structure is as erect as a

bear-skinned guardsman on duty with more than a little phallic swagger.

Turning corner of the table, reveals the last of the images, on a page

open from another book, a mid last-century guidebook to Cornwall. The

caption identifies the stone circle as The Merry Maidens, the Bronze Age

site at Boleigh.

There is seriousness about this grouping of objects and images. The

general tone is a sober cream and black, with colour muted into discrete

patches - the outline of cherry red in the guidebook’s binding, the

block of oatmealy grey from the other hardback cover and a shard of

mustard yellow supplied by a roughly shaped piece of glass. It is

propped up against the first two images, bridging them; it is the kind

of glass that distorts appearances. The profile of the ensemble is

noticeably angular, even edgy: it sets the tone for its reception. The

Maidens could almost be a maquette for a modernist memorial, raised up

on a plinth for easier viewing but with its purpose undisclosed.

Stringing elements together, therefore, is the core of the narrative

process. The women’s peaceful and defiant action at Greenham, which was

to continue for 19 years until it became a symbol of its own dedication,

was routinely belittled by the right-wing press, as much for daring to

disrupt the cherished image of women as homemakers and mothers as for

opposing the controversial government policy to site US cruise missiles

at airbases during one of the chilliest periods of the Cold War.

The Greenham women held hands to link themselves together as a human

blockade preventing the weapons from being driven into the base. (As a

result, they had to be airlifted at great cost.) Hands link and circles

form in morris dancing, an activity that defends another symbol, the

male preserve. Though that citadel is slowly crumbling, to purists, the

involvement of women is sacrilege, as a report in the Guardian newspaper

made plain as recently as 2019. The final paragraph of this tale is

supplied by the stone circle, to which all manner of fables have been

concocted about its origin, mostly by Victorians who were masters of

invented history and instant moralising folklore. From that time rose

the story that the stones were local girls who defied the Sabbath by

dancing and were punished by being turned to stone.

The myth survives, built on a characteristic misunderstanding of the

site’s Cornish name, ‘Dans Meyn’. Academics claim the words refer not to

dancing but only to the place being sacred for its pagan builders.

Still, the image closes a circle of meaning: the pervasive denigration

of women by authority, political, cultural or social, that is dominated

by men as their preserve. Is misunderstanding itself a credible theme of

this work? Or the need for vigilance? The work was completed in 2012

(and the oldest piece in this show; the others date from 2020-1) and

seems to be ahead of events. Brexit with that aspect of harking back to

a past that never quite was, had yet to happen and the #MeToo movement

was still to coalesce.

The value of this work, and the others in this show, is that they mine

our current reality as raw material for imaginary world building. In

Steven Claydon’s 'Playerless Games (Kamidana)', that world resembles the

scene after a gathering, the remains of a swanky party involving pills

at a place where the furniture has the finish of a well-maintained

holiday tan. The trigger for any interpretation is the glass-topped

structure under and over which the other elements are arranged. The

open-sided low metal base could be the height-challenged cousin of

Reynolds’s nearby construction. Rising no more than shin height, it

resembles an urban coffee table with carpet neatly contained beneath; on

top is a circular, broad-waisted earthenware jar containing dried

flowers. The glass top also harbours blister packs of the type

immediately associated with pharmaceuticals: many of the thermoformed

plastic pillows have been pushed through and emptied. A dusting of

pollen-fine powder, also golden, frames the table’s perimeter.

Illuminating this display is the strong bulb in the overhead lamp, slung

low by cables hanging from the ceiling.

Steven Claydon: Playerless Games

The scene could also be a pictogram for the word ‘aftermath’: after an

event, after people (sensed as having been present) have gone, after a

crime, even. The onlooker’s eyes dust the evidence for clues to the

story. While sifting the evidence, the basis of this initial, cynical

assessment starts to crumble. Or alternative routes open that introduce

unsuspected multivalence to this concentrated, intense scenario. The

assumption, fuelled by the high-roller gilding of the sitting-room

apparel, is that the packs, which the gallery notes list as ‘nine carat

gold plated copper’, may have dispensed psychoactive substance that

transported their consumers into an alternative headspace nirvana. Was

the aim of the ‘game’ in the title to satisfy needs unmet by material

excess? What is cultivated in the jar that calls for hydroponic light

still lit in daytime? The mind begins to inhale notions of modern

equivalents of the island lotus-eaters of classical mythology, indulging

in pleasure and luxury as an escape from practical concerns. The setting

of this peaceful apathy, however, is more like Canary Wharf than Grays

Wharf.

As with the other participants in 'Gathering', Claydon has provided a

work that articulates continuing themes in his practice. The clash of

artefacts and the diverse eras they come from has established itself as

a theme in his sculpture. Time and origin are bent almost to the point

of irrelevance, stripping an object back to its banal thingness – a fact

made up of properties: shape, scale, colour, surface. These details are

put on display and assessed as commodities of meaning and nothingness at

the same time. The combination, however, asks many questions: about the

nature of the dust, the reason for the packs, the jute of the matting

and the language of the title. At which point, Claydon appears drawn to

the risk of obscurity with the perceived demand his installations make

for specialist knowledge. The viewer feels pulled beyond that barrier of

difficulty by the natural desire to comprehend, to construct a credible

picture of overall significance, to resolve the dilemma. Claydon infers

the truism that full ‘understanding’ is an unattainable in artwork; even

its creator is denied it. As in everyday life, the gaps in certainty are

either acceptable or bridged by speculation, which is where narrative

arises.

‘Kamidana’ is not a word known to many in the west but is familiar in

Shinto households. As the indoor shrine, it is home to the ‘kami’,

spiritual holy powers. Ancient community ancestors are among these

deities, and because they co-exist with living in nature, they might

embody the values and virtues that those ancestors exhibited when living

ranging from good to evil. Knowledge assembled elsewhere in this show

throws a line to anyone beginning to thrash about for relevance in these

esoterica. The supposed presence of deities has been encountered often

enough already to apply that dimension here, even if help in making good

of it is less forthcoming. The gallery notes refer to the jar as

‘Momayama period’, which is the Japanese equivalent of late medieval in

European terms and to ‘tufts or flames from Tregeseal stone circle’ (as

well as to shredded money in resin’) among the components of this work.

Tregeseal belongs to yet another time: it is another ancient site in

west Cornwall, not far from St Just. Some academics claim that these

circles were devoted to the dead, like a sort of monolithic, open,

outdoor ‘kamidana’ or shrine. That view is disputed but consensus

appears to exist that the stones were reserved for supernatural

entities.

The formal cohesion of 'Playerless Games (Kamidana)' is matched by its

tactically diffuse references. The route into this captivating conundrum

arises solely from the artist’s choice of objects to put in one place

and held in that place by light (with all its connotations) and the

invitation to view the piece in whole and part. The piece exudes

confidence in itself and its inscrutability, factors evident elsewhere

in Gathering which contribute to the show’s admirable openness to the

viewer’s imagination. Another feature of the show is the relationship

between unconnected works by 10 artists known to the selectors and who

share Cornwall as a common denominator. Birt and Sewell are the newest

arrivals in the predominantly rural west of the county and their work is

no less representative of a collective fascination with the specific

topography of the region. To a fair extent, this group came together

because of that shared interest. Along with its recent art history, the

Cornish heritage of myths and rituals has for decades been a mixed

blessing, and almost a prerequisite, for artists working locally,

providing the groundwork for and handicap to their serious progression

beyond a stifling parochialism to higher levels of dialogue. The artists

gathered here appear to have survived its worst aspects, linking with

its broader cultural and social importance in the interconnecting energy

of the universe.

'Gathering' at Grays Wharf, Penryn, 28 May-13 June

2021, was organised by Jonathan Michael Ray and Verity Birt.

© Martin Holman 2021. The author is a writer based in Penzance and a

regular contributor to Art Monthly and the Burlington Magazine.

See

http://www.artcornwall.org/exhibitions/Grays_Wharf/Gathering.htm for

more installation shots.

14.7.21 |