|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Lost in the Stars: Lockdown, time & space

The Mirror Paintings of Michelangelo Pistoletto have been reflecting vibrant, fluid objectivity since the first in this infinite series of was polished off in 1962. They are Mirror Paintings because of the stainless steel sheets upon which this Protean figure lays random, everyday silkscreened images have a mirror finish. In a Mirror Painting, the time is always set to now, regardless of when any particular example was made. ‘It seems clear to me,’ Pistoletto once said, ‘that the space in which this reflection takes place is neither limited nor exclusively individual, but is the cosmic space of totality and, therefore, of everyone.’

I am not going to write about Pistoletto, however much I would like to. He is an artist whose ideas and work I esteem highly. I am thinking, instead, about space and about time, and that is my subject. In the global health emergency during which I have set about this diversion from the unstoppable news stream of virus death and prevention, there is time for ruminations of this nature. If Bob Dylan can release a seventeen-minute song, I thought, as the world knuckles down to being home alone with its own resources, what is more a track that dense with reference and metaphor, then, if these restricted days will achieve anything, they will have made time for time. Like most people without an essential job to do (after all, I am a writer: when have I been essential?), my public life has been locked down to a few activities. These are permitted beyond the physical boundaries of my home to be performed in a limited amount of time. My relationships are officially proscribed: distance is the keyword. I have become acutely conscious of the space I occupy at any one time, and of the time that is mine to fill or leave fallow. Before moving on, though, I will add a further observation about Pistoletto. His mirror paintings have a curious relationship with time. In fact, they are not just reflections of the present. Instead, these effulgent surfaces throw the present back to us. When we look into the mirror plane, there is no instant replay because the image is never the same from one second to the next. The artist pleases me by insisting on calling them ‘paintings’ (as, indeed, the first examples were: until he switched to silkscreen, the images were created by hand and brush on thin paper before being stuck to the polished steel). Paintings traditionally have a dimension of time that uniquely binds the surface to a discrete space for illusion, when the fictional play of events unfolds into our individual perceptions. The two dimensions are looped into an eternity of actions. But these paintings never cease remaking themselves in the image of the viewer. The tyranny of the infinite present has the only intensified in the years since Pistoletto set about projecting the present onto itself. Is that why, almost sixty years later, he continues to make new mirror paintings? A whole generation has exploited the gift of play, pause and rewind to review the present moment. Hindsight is said to be a wonderful property. Yet when looking back, remember the situation of those for whom that moment was their present. In the 1970s some biologists foresaw the elimination of the planet’s resources by population growth leading the inevitable exhaustion of the planet as sustainably habitable. The end was, they predicted, in sight. Or was that short sight? The flaw in their forecast of the future was their own fixation with the present. ‘If we keep going on like this, then...’ Unlike the present, the future allows change. There are multiple presents. Simultaneous

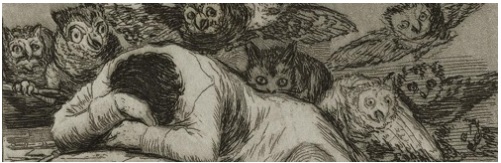

time frames strut across wholly abstract modes of articulate thought and

logical investigation like so many horses trotting round the paddock.

Some are universal: unconsciousness has a discrete time structure

belonging to the sleep of reason that, as it did for Goya, can bring

forth monsters. Others might be unique to Western sensibility and

consciousness: slavery ironically liberated time for those lucky others

in Classical Greece to devote themselves to thought. An abominable

practice of captive labour freed time for ideas.

Still thinking about those multiple forms of the present while turning the pages of a book devoted to On Kawara’s so-called Date Paintings, I am struck by how this artist referred to present, the past and the future all at the same moment. Each painting is a calendar date, recorded as if mechanically printed in white characters on a monochrome background – of blue, or black, or red. There are many of these paintings because he started making them in 1966 and continued the task right up to his death in 2014. A painting was completed during the day of the date it displays. If its making went beyond midnight, it was thrown away because, by the next day it had become, well, a type of history painting. Registering the date during its lifetime kept that day alive. By a minute after midnight, the event that it had been had passed. Like Pistoletto’s Mirror Paintings, a date painting passes into a new dimension, that the ‘cosmic space of totality’ that Pistoletto talked about. That day lies in wait to come alive when somebody encounters it – and that could be at any date in the future. With the minimum of material, vast feeling is evoked. That is the beauty of this idea (and others like it in art). Which is why I like On Kawara’s own assessment that ‘The work [of art] is of value only if it exposes, beyond date and time, a rupture in the present: the force of consciousness occurs precisely at this moment of encounter.’

March23,2020 Lockdown date painting: Hommage to On Kawara, 2020

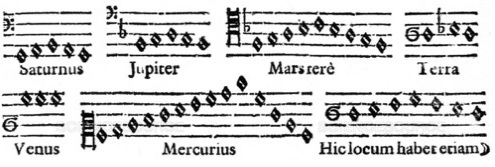

The vanity of humans might once have interpreted the stars as communicating with man. The celestial bodies, they assumed, were messaging the geometry of the Almighty’s plan. The universe was the image of God: the sun was the Father and the stellar sphere was the Son, with the space between confirming the truth of the Holy Spirit. The German astronomer Johannes Kepler refuted Aristotle’s geocentric theory with his own treatise, Harmonices Mundi (literally the ‘Harmony of the World’). It saw the light of day in 1619 and in it Kepler illustrated the motion of the planets in time as corresponding with musical intervals, set out on parallel staves. The music of the spheres, however, was only audible to the soul. Even the dissonances and consonances that make music a pleasure to hear resembled the intelligent geometry that organised the solar system.

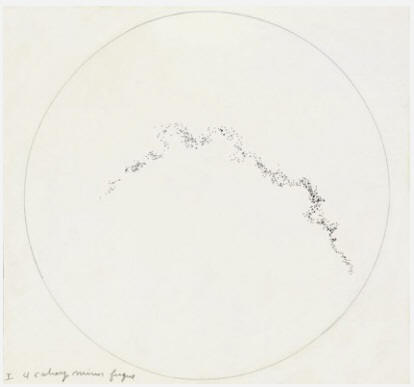

Anastasi drew for the exact duration of each prelude and fugue. For all that time – he might have five minutes to draw or the luxury of eight or nine – he made marks on a piece of paper without any reference to the rhythm of the music. Moreover, he kept his eyes closed. The marks produced by this unusual, ‘hand to mind’ technique were predominantly dots. Did he find himself making dots because, at some unconscious level (dare I suggest even a spiritual prompt?), the music made him think of constellations of stars? Or did Anastasi decide that, seeing the drawings had lots of dots gathered in patterns like trails of celestial light, he might as well call them Constellations? If the drawings offer some sort of notation, the music they transpose is inaudible. And his universe was negative: the ‘stars’ are dark and the ‘sky’ is white.

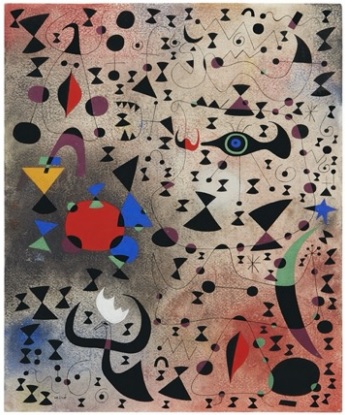

If Darwin’s revelations about the slow evolution of life-forms two centuries after Kepler - and following Darwin’s five, arduous years at sea - did not dislodge religious education, then the forensic gaze into deep space achieved by the Hubble Space Telescope must have accomplished the task. If ever an instance of ‘us looking at them’ arose, then Hubble was it. Peering into infinity, the prospective lenses of the spectograph on board the satellite did not pick out the enthroned Almighty. The late twentieth-century price tag was also astronomical, exceeding several hundred million US dollars (not counting subsequent in-air refits). The project was big on numbers. But the outlay pushed open the nursery door of planets. Once the onboard cameras began whirring in 1995, unprecedented views of spiralling, elliptical shapes came into view – Milky Ways that had not yet had time to build themselves. Stellar winds rained on the telescope’s deep-drilling sightline from newly-formed stars and clusters of embryonic constellations. Calculations in hundreds of millions once more captured the imagination, then blew it. This time the numbers counted light years of distance, the time light needed to travel from those infant constellations for an encounter with the mechanical eye of Hubble. Like On Kawara’s Date Paintings, deep space ruptured the present. Trained on the whirlpool galaxies swirling round cores of white light, Hubble detected black holes everywhere, feeding on their own surroundings. Their rapacious appetite for sundry annihilations graphically subverted human capacity to imagine the gastronomy of the most far-out of outer space. The colour of memory is variable, even non-descript. A recent memory contains the vivid colours and poetry of Miró’s gouache imaginings of the Constellations. To claim that the colours sing is not farfetched. They also seem to move. Miró claimed for the completed series of small paintings that they were ‘A new stage in my work, which had its source in music and nature.’ He created in twenty-three images over twenty months from January 1940. There is the night sky in blues and greys, and prominent within it is the shape made by two triangles, with one balancing on the apex of the other. It tilts with gaiety this way and that in concert with the crescents, dots and zigzags around it, like a carton apple core in space or the silhouette of black bow tie. Indeed, there are dozens of these shapes, in big and small versions, speckling Miró’s nocturnal visions. It is an hourglass, jangling sandy pockets of time back and forth so that it is simultaneously a sparkle of light, but negative light, captured in black.

Joan Miró, Femmes au bord du lac à la surface irisée par le passage d’un cygnet (Women at the Edge of the Lake Made Iridescent by the Passage of a Swan). May 14, 1941, gouache and oil wash on paper, Private Collection © 2017 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Have we been here before? The spectacle, if

not the fact, of the reality of deep infinity was anticipated by the

deployment of full illusionistic, three-dimensional Baroque quadratura

in the seventeenth century. The ceiling frescoes of Andrea Pozzo, the

inspired Jesuit painter, architect and stage designer, continue to blow

the roof off the interior vault of the church of Sant’Ignazio di Loyola

in the centre of Rome. Pozzo dreamed the vision of eternity and Hubble

portrayed an emergent future. The painter was finally vindicated by the

NASA draughtsmen who colourised the dawn of Milky Ways with a palette

very much like his own but transported at inconceivable speeds of light.

He was not writing about telescopes in space, of course; Baldwin was dead before Hubble blasted away from the launchpad. Nonetheless, now that our experience has been expanded beyond theory into pictures of what has happened in the trackless universe, who would not choose a little fantasy to leaven reality? The general truth of Baldwin’s observation expands like our awareness of the world around us: the relentless news cycle has penetrated into every cavity within our minds.

From time to time I stand at night on the promenade in front of the seaside town where I live. Instinctively I look towards the horizon. That is where the sky falls down to the water. Moonlight orchestrates the tide and an artificial constellation of lights shine from vessels crossing the bay: from the beam trawlers, gill netters, long liners, even little crabbers to the container ships anchored in the channel. The blue above phosphoresces with torch beams from billions of years ago. Maybe science alone has the subtlety in its maths to embrace these immense dimensions. Every streetlamp along the promenade is connected to the next by a string of white lightbulbs. They are turned on at dusk in winter and shine through the night. They evoke the pleasures of a celebration or a summer garden party. Every so often a gap appears in the line undulating into the distance; for the blank bulbs, their shining is finished. Poetry and melancholy co-exist in that display, the passage of time when bright things fade for good. I am stopped in my tracks each time I turn a corner and happen to encounter the untitled light-string works by Félix González-Torres. The artist entrusted their installation to the directors of the museum galleries where the simple white bulbs would be looped, draped, and wrapped around floor and walls. No two outings of these creations is ever the same. The themes are loss and regeneration; the first light piece was made after the death of the artist’s partner. When a bulb gives out, the institution is authorised to replace it immediately. That is more than González-Torres could do for his lover. So suspended in the lights is an unattainable wish, a love letter to existence passed, present and, if we ever are re-united, still to come. González-Torres was preoccupied with the

fleeting nature of life. Everything must change; nothing stays the same.

As a small child, I could not understand how the same star formations an

adult pointed out to me in the sky were also visible to someone else

standing on another spot in a different location. That other person

might be thousands of miles away in Europe or North America. Perhaps I

can freeze time. At the precise same moment, we were looking at the same

event that happened perhaps a billion years ago.

Unless credited otherwise, photographs are by the author.

This text was commissioned from the Penzance-based writer

Martin Holman for the online exhibition Real

Time,

curated by Damien Roach, at

Seventeen, London.

It is reprinted here with permission.

http://www.

|

|

|