|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Alfred Wallis and after: naive and outsider art in Cornwall Editorial: Rupert White

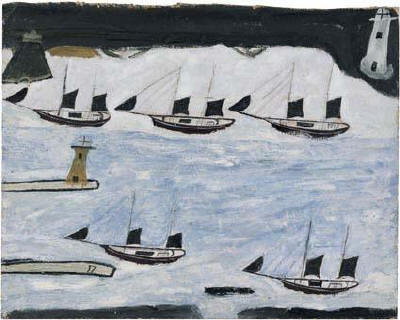

In the 20s Nicholson joined and became the influential chairman of the Seven & Five society. The approach common to many of the Seven & Five artists is described by Charles Harrison (in English art and modernism) as being: 'a grotesque and attenuated reflection of the Romantic notion, for which the writings of Jean Jacques Rousseau are the locus classicus, that there is a vigour and an ethical value in innocence and this is dissipated by technical sophistication'. It was towards the end of this phase of his career, in 1928, that Nicholson came to Cornwall, and whilst staying in Pill Creek near Truro, travelled to St Ives and discovered the paintings of Alfred Wallis (above right). Their unique use of materials in particular captivated him, and of course their primitivism which seemed unaffected by convention or taste. There was a sense that he and Christopher Wood had discovered Britainís own Douanier Rousseau: a real, true and authentic voice, unspoilt by training or civilisation. This encounter is now rightly considered the founding myth of St Ives modernism, and the presence of Wallis was important to many if not all the artists that worked there subsequently. Most of the St Ives modernists were receptive to the idea of the untutored artist living amongst them. Many, like Nicholson himself, were essentially art school drop-outs or 'outsiders' themselves, and someone like Peter Lanyon barely had any art-school training. This was partly because even the most progressive English art schools were felt to be out of touch and behind the times.

But what is the status of naive or outsider art now in Cornwall and elsewhere in the 21st Century? Does post-modernism have the same relationship to the outsider as modernism did? In fact the term 'naive' tends to be used less frequently than it used to be. Perhaps there is an acceptance now that its not possible to live in a Western society and be truly naive: unlike Wallis we can all go to school and we all have access to the internet and mass-media, so can inform ourselves about art and other cultural matters if we choose to. The issue becomes about how we exercise that choice and e.g. whether its important or necessary to be informed about international trends in art. Some artists

believe that it is not necessary, and instead recognise virtue in

being 'outsiders', in the sense of being outside such trends. Spontaneous Combustion, an event that ran in both

2006 and 2007, was an energetic and inclusive show that

played well to local audiences. The essay by Jo Forsyth (reproduced on

the artcornwall.org forum) eloquently drew out some of the issues at

stake, and referred approvingly to Dubuffets definition of Art Brut in

1949:

It was this latter category that the organisers of Spontaneous Combustion were most interested in supporting: 'Between the commercially driven work and the state funded activities there exists a cavern of overlooked outpourings of creative expression. It is in this cavern that we started to look with our outside eyes'. And because Cornwall is relatively remote from the rest of the country, there was an implication that it attracts and encourages people who prefer to detach themselves from mainstream culture, and that this might be a good thing. Forsyth's description is a useful one. If it is accepted as a premise, it raises a number of issues, including understanding how the three strands, a), b) and c) are related to one another today, and speculation as to whether, for example, they can ever interact as they did in the days of Ben Nicholson and Alfred Wallis, when outsider and avant garde, for nearly a generation, merged closely together.

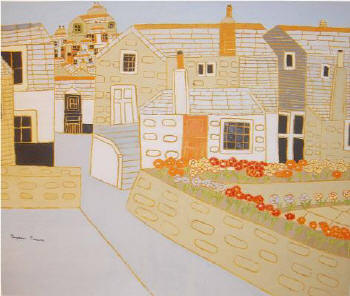

If there is a merging of strands at all now in Cornwall it is naive art c) and tourist art a) coming together. Bryan Pearce increasingly exemplifies this new market. Artists like John Dyer and the late Fred Yates in Cornwall, and to a lesser extent Simeon Stafford, have also proved themselves to have broad popular appeal in attaining a level of commercial success unthinkable to Alfred Wallis in the last century. Meanwhile I would suggest that international art trends have moved further away from interest in the modernist 'naive-outsider'. Within the art academies the idea of self-expression, as either desirable or attainable came under sustained attack both theoretically with structuralism and post-structuralism, and in art with minimalism and conceptualism, such that there did not seem much hope of the museums ever seriously having to submit to the basic premise of Art Brut, purity of self-expression, again during our lifetimes. (It is no accident that interest in Freud's theories of the unconscious have also been on the wane during this period, subjectivity having been replaced by intersubjectivity, or an emphasis on thinking about art in the public sphere). In short the debate seems to have moved on and for the foreseeable future, the outsider artist, at least as they were conceived in the 20th century, will be destined to remain outside.

*Though as I write this a new outsider art is promising to make in-roads into the biggest museums with this Summer's 'Street Art' by the Tate. Street art is a form of outsider art, but it is different from the Art Brut described above because of its political content, community engagement, and use of new media.

|

|

|

In

fact for

most of the last decade or more it has seemed unlikely that they would

ever come together again. The renewed interest in Henry Darger

(picture above) in America, seems the exception to prove the rule*.

It is likely that many of

the 'lessons' taught by the naive untutored artist in the last century have been

learnt: or to put it another way, to the contemporary 'avant-garde' these ideas are no longer radical because they

have been

already absorbed into Surrealism and other forms of early and

mid-century modernism, and so they are already present in art that is

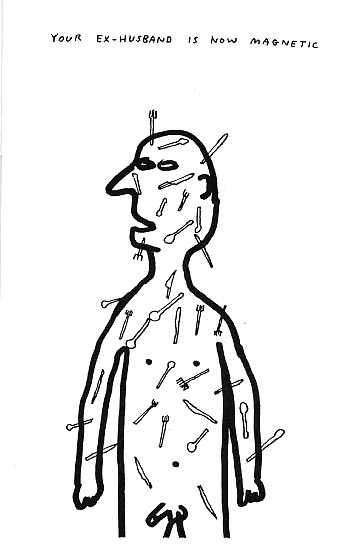

made now. In this sense they have been recouped by the art institutions, hence, for example, we see someone like Tracey Emin or David

Shrigley (left) adopting the look of naive art to make culturally

sophisticated work (Shrigley learning this 'naive' style on an MA in Glasgow,

and Emin at the RCA!).

In

fact for

most of the last decade or more it has seemed unlikely that they would

ever come together again. The renewed interest in Henry Darger

(picture above) in America, seems the exception to prove the rule*.

It is likely that many of

the 'lessons' taught by the naive untutored artist in the last century have been

learnt: or to put it another way, to the contemporary 'avant-garde' these ideas are no longer radical because they

have been

already absorbed into Surrealism and other forms of early and

mid-century modernism, and so they are already present in art that is

made now. In this sense they have been recouped by the art institutions, hence, for example, we see someone like Tracey Emin or David

Shrigley (left) adopting the look of naive art to make culturally

sophisticated work (Shrigley learning this 'naive' style on an MA in Glasgow,

and Emin at the RCA!).