|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

Awake! Albion Awake!In an excerpt from his book 'This Enchanted Isle', Peter Woodcock discusses William Blake (1757-1827) and his influence on subsequent generations of Romantic and Neo-romantic artists. Published in response to the Dark Monarch at Tate St Ives.

Madman, visionary, revolutionary, genius, even today William Blake is considered to be all of these. His writings still reverberate in the twenty-first century, and his engravings and watercolours still excite and disturb.

The capital was a city seething with riots and disorder. Britain was under threat from France, sedition was in the air, revolution underfoot. Blake was sympathetic to radical politics; it is said that he knew Tom Paine and helped him flee the country. As well as politics, Blake embraced the teachings of the Swedish theologist Emmanuel Swedenborg with enthusiasm, but later in life rejected them, finding more sustenance in the writings of Paracelsus and Jacob Boehme. Boehme in particular had a profound effect on Blake with his concept that Man contained not only the Sun, Moon, Stars and universe within him, but God as well, which resonated with Blake's own beliefs. It was while apprenticed as a young man to the engraver James Basire that Blake was asked to make drawings of the royal tombs in the chapel of Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey. This great Gothic masterpiece, 'a book in stone' which Victor Hugo called the Abbey, thrilled the young Blake. The very essence of the architecture with its pageant of British history encased in stained glass, carved effigies and ancient tapestries, struck a deep chord in him. While drawing in the Abbey he had more visions, of monks and priests. It was as if he were witnessing the archetypal realm of the nation, something to which he would return for the rest of his life. Even the Archangel Gabriel appeared to him in majestic glory, and moved the universe.

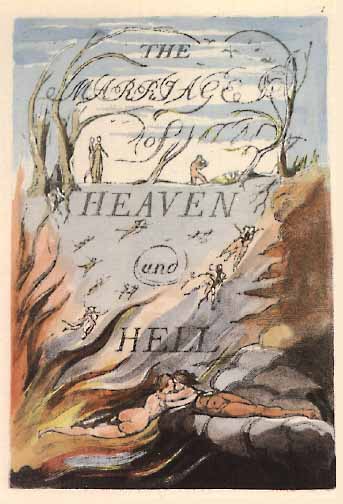

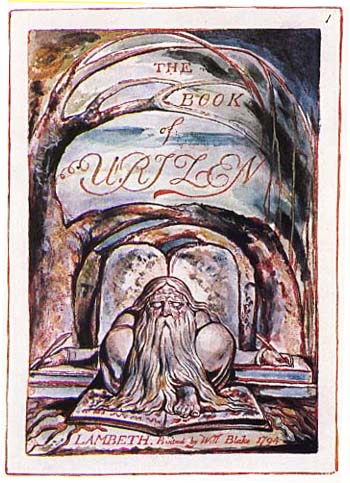

In 1779 Blake enrolled at the Royal Academy of Art as a student. The principal was Sir Joshua Reynolds which was unfortunate as Blake detested Reynolds' views on art as well as his painting. Forever battling against the practice of 'copying nature', Blake developed his own extraordinary visionary skills. Mainly influenced by his own inner world, he created a mythical realm which to many of his contemporaries appeared on the edge of madness. As a skilled and creative printmaker Blake developed his own method of reproducing his images and writings, combining a mixture of relief etching on copper plates and hand-coloured prints, executed by himself and his wife Catherine. The results were unique, echoing not only references to the old masters but to the pamphlets, leaflets and radical publications produced in London during his life. Blake and his wife left London in 1800 and moved to Felpham for three years. During this period Blake was highly prolific. Among other major writings combined with images, he produced The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Book of Urizen, Songs of Experience, The Book of Los and The Four Zoas. It seems that Blake had a fiery temper. On one occasion an argument with a soldier outside his cottage resulted in Blake being charged with high treason. Blake was anti-monarchist and had supported the French Revolution until news of the Jacobin slaughter of opponents became known in Britain. Fortunately the case against Blake collapsed due to insufficient evidence. But it shook him and aggravated the nervous disposition which afflicted him all his life.

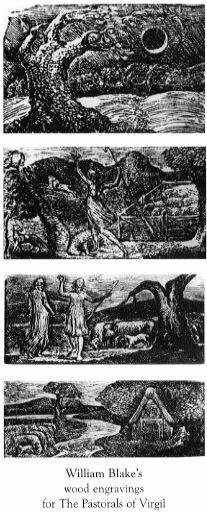

It was unfortunate that Blake was born when he was; if he had been born a hundred years earlier, his visions would have been acceptable, almost commonplace. In the eighteenth century the Newtonian universe was rapidly encroaching. The rise of materialism, which Blake warned against, was closing the doors to men and women of vision. With the Neo-Romantics of the twentieth century, Blake's images and writings struck a deep chord. Nash, Sutherland, Piper and Vaughan in particular admired Blake, who along with Samuel Palmer, conjured up an archetypal realm. Because of the restrictions of the Second World War, artists in Britain were thrown back onto their cultural roots. It is easy to see why they revered the work of Blake and Palmer. If Blake portrayed an ancient land called Albion, in which angelic and demonic forces were drawn from the imagination rather than from reality, Palmer caught an idyllic, Arcadian mood, particularly in his Shoreham pictures. Both artists represented an archetypal view of Britain which was free of the pseudo-chivalry of the Pre-Raphaelites. However, there is an odd discrepancy here, as all the Neo-Romantics revered nature and based their work on actual observation which Blake refuted, preferring to work from his imagination or his 'visions'. During the latter part of his life, Blake, regretting having spent so much time reconciling his creativity with commercialism, burst into a frenzy of activity producing some of his most complex and beautiful poetry and images. His colours became more vibrant as if describing the inner world he saw. Some of the most dazzling images are to be found in the wood engravings for The Pastorals of Virgil. Although small in scale, they are like jewels glowing with an inner light, their inky blackness as deep as the night sky, their attention to detail ravishing.

Always impoverished, Blake, with the help of his wife Catherine, worked until the end on his paintings and engravings. When he finally died in 1827, he died singing, his face enraptured by the visions he was seeing. Blake above all was prophetic and had insights which are of relevance today. Not only did he foresee the rise of materialism, he created his own spiritual universe based on a mystical, and some would say heretical version of Christianity, incorporating elements from Hinduism, alchemy and ancient British mythology. He also held strong views on sexuality: he saw war as a direct result of sexual repression and believed in a healthy, robust sexual life. In the preface of his epic poem Milton there is almost a call to arms, which poignantly reverberates in today's age of cultural consumerism. "Painters! on you I call! Sculptors! Architects! Suffer not the fashionable fools to depress your powers by the prices they pretend to give for contemptible works or the expensive advertising boasts that they make of the works." The political fervour and fascination with underground religious beliefs and occultism of the eighteenth century was echoed two hundred years later in the Sixties, when many of the beliefs of the earlier period resurfaced. As well as political ferment there was an explosion of interest in such beliefs as the Western Mystery Tradition, paganism, Druidism, divination, sacred geometry – the whole concept of the landscape of Britain laid out in a magical tradition.

|

|

|

Born

in Soho, the son of a London hosier, Blake had little formal education,

but was steeped in the Greek and Latin classics, Milton and the Bible.

When his younger brother died from consumption aged twenty, an exhausted

Blake, who had nursed his brother throughout, said that he witnessed his

brother's soul ascending towards heaven. Blake had seen angels and

heavenly forms since childhood. His father reprimanded him for saying

that he had seen the prophet Ezekiel sheltering beneath a tree. Blake

saw angels in a tree on Peckham Rye and throughout his life he conversed

with spirits. Growing up in eighteenth century London, he was in the

midst of a whole world of visionary and dissenting religious teachings.

As a Londoner, the capital was where he witnessed most of his visions.

Wandering through each chartered street, he experienced a visionary city

– the Four-Fold city which could be witnessed by anyone who shed the

dust from the mundane world.

Born

in Soho, the son of a London hosier, Blake had little formal education,

but was steeped in the Greek and Latin classics, Milton and the Bible.

When his younger brother died from consumption aged twenty, an exhausted

Blake, who had nursed his brother throughout, said that he witnessed his

brother's soul ascending towards heaven. Blake had seen angels and

heavenly forms since childhood. His father reprimanded him for saying

that he had seen the prophet Ezekiel sheltering beneath a tree. Blake

saw angels in a tree on Peckham Rye and throughout his life he conversed

with spirits. Growing up in eighteenth century London, he was in the

midst of a whole world of visionary and dissenting religious teachings.

As a Londoner, the capital was where he witnessed most of his visions.

Wandering through each chartered street, he experienced a visionary city

– the Four-Fold city which could be witnessed by anyone who shed the

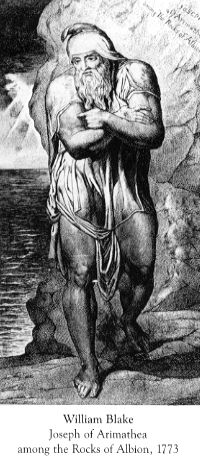

dust from the mundane world. His

first engraving is Joseph of Arimathea among the Rocks of Albion

(picture above right). A rather solid patriarchal figure broods on a

rugged coast against which the sea is raging. It is interesting that

Blake chose this figure (although biblical figures were popular as

artistic subjects in Blake's time) for Joseph was none other than the

uncle of Jesus who brought the Holy Grail containing the blood of Christ

to Britain and created the first Christian church in the land at

Glastonbury. Blake's immortal poem Jerusalem relates to this

event.

His

first engraving is Joseph of Arimathea among the Rocks of Albion

(picture above right). A rather solid patriarchal figure broods on a

rugged coast against which the sea is raging. It is interesting that

Blake chose this figure (although biblical figures were popular as

artistic subjects in Blake's time) for Joseph was none other than the

uncle of Jesus who brought the Holy Grail containing the blood of Christ

to Britain and created the first Christian church in the land at

Glastonbury. Blake's immortal poem Jerusalem relates to this

event. During the later part of

his life Blake, through his acquaintance with John Varley, himself a

fine water-colourist, drew many portraits of spirits, including

Socrates, Herod, Voltaire, Richard Coeur de Lion and the Man who built

the Pyramids.

During the later part of

his life Blake, through his acquaintance with John Varley, himself a

fine water-colourist, drew many portraits of spirits, including

Socrates, Herod, Voltaire, Richard Coeur de Lion and the Man who built

the Pyramids. Towards

the end of his life Blake became revered by a group of young artists

called the Ancients. They were so called because they considered modern

society debased when compared with older civilisations. Among the group

was Samuel Palmer who worshipped Blake. Palmer was also a visionary but

the Ancients did not have the political fire born from experience, which

Blake had. Their art was more concerned with an idyllic pastoralism

which did not reflect Blake's views.

Towards

the end of his life Blake became revered by a group of young artists

called the Ancients. They were so called because they considered modern

society debased when compared with older civilisations. Among the group

was Samuel Palmer who worshipped Blake. Palmer was also a visionary but

the Ancients did not have the political fire born from experience, which

Blake had. Their art was more concerned with an idyllic pastoralism

which did not reflect Blake's views.