|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Remembering Rose Finn-Kelcey Rupert White

When I was 30, I moved to London with my young family. I'd spent nearly 5 years in Cornwall working as a doctor, but, having made art all my life, in 1996 was accepted onto the Fine Art MA at Chelsea. Naive to art school as I was, to me one of the best things about the course was the visiting tutors. Ex-Chelsea alumni like Chris Ofili and Peter Doig were regular visitors, and I remember having one-to-one tutorials with people like Gavin Turk, Tracey Emin and Martin Creed. One afternoon I was also booked for a tutorial with painter and presenter of the Turner Prize, Matthew Collings, but ended up giving him the slip after my family (I had two pre-school kids at that stage) had protested noisily about having to wait in the car outside my studios.

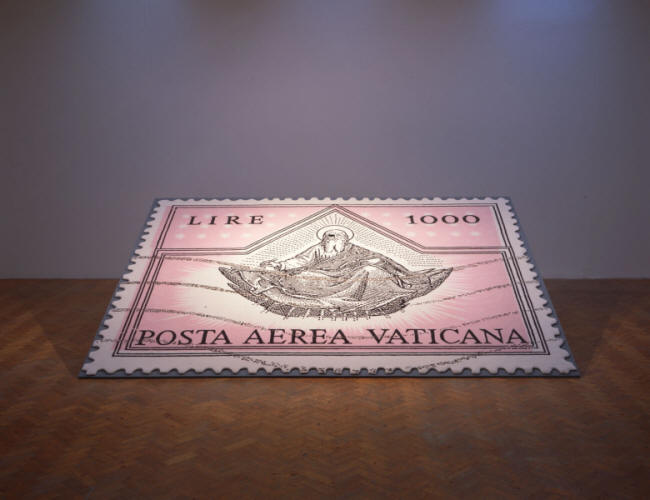

Jolly God (1997)

The personal tutor allocated to me at Chelsea was Rose Finn-Kelcey. She was already in her 50's, but was respected by younger artists then as someone who, in the 70's had seemed to anticipate the 90's in making conceptual art that was smart, socially-aware and playful in just the right combination. She also had the street-cred that came with being one of the early Saatchi artists, despite being of a different generation to most of the yBa's, and she had recently had a successful show at The Chisenhale in which she showed the memorable 'Steam Installation'. My abiding memory of Rose, however, is the lightness of her step as, wearing ballet pumps and red-striped cotton trousers, she would move around my studio space with the grace of a dancer. She had a bright, engaging manner and a flair for Socratic questioning, or at least for getting you to consider your work in ways you hadn't done previously. We used to meet every week for the best part of an hour, and although she was happy talking ideas, she'd moved on from the austere conceptual or process-based art of the 60's; something I was still obsessed by. Instead she would stress the importance of the physicality of the art work; in particular its visual impact and surface finish, both things I was suspicious of and in denial about. I would naively condemn a work of art by saying 'but it's just a look', or 'it's all just surface' or 'it's too fetishistic', to which she would always reply: 'of course it is. It can be no other'. She, of course, was very attuned to these sensual qualities in her own work of the 90's.

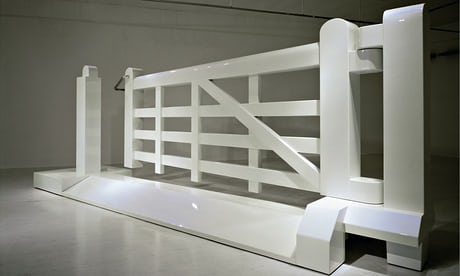

Pearly Gates (1997)

We also talked about Bas Jan Ader, an artist I was interested in then, and the notion of saying goodbye, of self-erasure and artistic suicide. She warned me against going down that road. She liked a small work I made on paper, though. It compared Bruce Nauman to Max Wall, the music-hall comedian who acted in Samuel Beckett's plays. She suggested that I write to Nauman about this, as she was sure he would be interested. I never did. Towards the end of my time at Chelsea, Rose started working towards one of her biggest shows: a solo exhibition at Camden Arts Centre, and, demonstrating her methods in practice, she would give me regular updates regarding her preparation, as she organised for a carpet to be made in Norway based on a postage stamp once issued from the Vatican, or a life-size farm-gate based on a toy model to be coated with a special pearlised paint ('Jolly God' and 'Pearly Gates' respectively, pictured above). We talked about her life growing up on a farm, her feelings about God, religion and the after-life: all things that featured a lot in this later work. Like many artists - and indeed people - in today's secular society, I think she had a strong spiritual yearning, but she also had a rare ability to find the spiritual in the ordinary and the everyday. And her art very much reflected this.

Rose Finn-Kelcey (b.1945 d.2014) was at Modern Art Oxford 15/7/17-15/10/17 see 'exhibitions' |

|

|