|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

What is Ecological Art? Richard Povall Dr Richard Povall is Founding Director of art.earth and Visiting Research Professor at Ulsan National Institute of Science & Technology, S. Korea

This, of course, is the wrong question. The word ‘Ecology’ is usually used as a term of science, and often used interchangeably and erroneously with other words such as ‘environment’, ‘environmental’ and even sometimes ‘nature’. This ecology is a noun, a ‘thing’, something to study and be studied. Most dictionary definitions say something like this:

Ecology noun 1. The branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings.2. The political movement concerned with protection of the environment

So correct usage of the word implies a process (certainly in its primary definition) - something ever-changing and ever-adapting, relational, and self-referential. We often forget this: we look on ‘ecology’ as a fixed thing, oppositional and fragile, easily damaged, non-repairable and non-repairing. Some art – often art that is rather bluntly trying to tell a story, or define a truth, or send a message – falls into this trap, labelling itself as ‘ecological’, all the while becoming enmeshed in binary rights and wrongs, speaking only absolute truth.

Beyond definition But little in this world is simple. Complexity theory and Holism can be seen as central tenets of Ecology, where ‘complexity’ refers to the modelling that helps us look at systems in which very many independent agents are interacting with each other in very many ways – generally beyond the capacity of the human mind to unravel and understand. We still, in truth, have very little understanding of biological systems because they are so complex; patterns and behaviours on the small scale do not necessarily map to patterns and behaviours on the large scale, and our understanding of the whole is woefully less that the sum of the parts. Think, for example, of the quadrillions of inter-reacting proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that make a single living cell – or indeed the large groups of mutually independent individuals who make a city, or a community, or a society. These are complex systems we cannot begin to understand – but we know they work.Ecologists also speak of emergent and self-organising phenomena as defining qualities of ecological systems. Once again we find these phenomena hard to explain or understand, but we understand that emergence and self-organisation are qualities essential to life at all levels, and we understand that such systems are adaptive and self-healing. To an artist, this is familiar territory, endemic to the creative process. Ecosystems are more complex than their parts - we do not yet understand how these self-organising systems work as a single whole. Gaia Theory (Lovelock & Margulis) suggested more than forty years ago that our entire planet is itself a self-organising and theoretically self-healing single organism. It’s no accident that this was also the period – the 1970s – when the ecological art movement bloomed. This was clearly a time when we were asking some fundamental questions about the planet and how we live here.Holism – the understanding that nothing can exist independently and that the parts of the whole are in intimate interconnection and cannot exist without one another – must be seen as central to ecological thought: an ecologist will always strive to find a holistic description of a system rather than a simple ‘scientific’ reductionist ‘solution’.Behaviours, too, are complex and often outside our most fundamental understanding. We know little of how the brain functions, do not really understand consciousness, memory, or communication (both intra-species and inter-species). We can see these phenomena, measure them, smell and taste them, analyse them: but no reductionist model can really offer explanations of how such complex behaviour systems function. Science flounders here. Fifty years ago, Gregory Bateson reminded us that '...mere purposive rationality unaided by…art, religion, dream, etc. is necessarily pathogenic and destructive of life;…life depends upon interlocking circuits of contingency, while consciousness can see only such arcs of such circuits as human purpose may direct’.’ Bateson refers to this as ‘wisdom’ rather than mere consciousness.’And to complete this introduction I should mention social ecologies: emergent patterns of behaviour amongst groups of species, whether they be human, animal, or plant-based. Social ecologies are vastly, ineffably, complex - like the human brain - and yet we can see and feel these emergent properties every time we speak with someone, watch a political rally, visit a shop or a festival, or observe natural systems and populations interacting.

Home But the etymology of the word ‘ecology’ takes us somewhere else: oikos means, simply, ‘house’, although perhaps we should better understand this as ‘home’. This is beginning to feel helpful. If we think of our notion of ‘home’ as a place of comfort and security, a place where families learn to love and to live, a place where interactions are crucial – the place we come home to and without which we are lost – then we begin to understand how art and ecology can comfortably co-exist. The essence and importance of ‘home’ is that we all need one in order to be in the world and begin to function as human beings. As artists, if we have not found our ‘home’, our place in the world, then the work we produce is empty of meaning, empty of soul, empty of spirit. Remove any bioscientific or biomechanical element, strip the concept of ecology back to raw properties such as ‘complex’, ‘emergent’, ‘self-organising’, ‘non-reductionist’, ‘systems’ and ‘behaviours’, and embrace broader concepts such as social ecologies and even creative ecologies, and we are beginning to speak the language of art as well as of nature.

Rejecting definition For me, there can be no ‘ecologic art’ but only ‘ecological arts practices’. The distinction may sound and even look subtle, but one is an object, an output, a solid thing; the other a process, an emergence, a property. '[Ecological] Art-making…becomes a form of attention to the patterns and processes of the universe, which gives voice to the minute infinitude of human experiences within it… [Art] can then be understood less in terms of object or outcome than as a whole body activity, a choreography of material and emotional processes in which the work itself is shaped to - inhabits - the context it describes…How we perceive things is what they are to us, and so how we act in relation to them. Art draws attention…to acts of observing, perceiving, interpreting, reacting and becoming…Art of place is contingent, relational and referential.' (Little)The poet Mary Oliver (quoted in Little) reminds artists to ‘pay attention; this is our proper and endless work.’ The British philosopher Timothy Morton has written at length about capitalised nouns such as Nature and Ecology, worrying that such terms become self-defeating and antithetical. In his 2010 work he encourages us to speak about ‘the ecological thought’, which essentially is about Being, not about a thing. He places an emphasis on the definite article: this is not merely ecological thinking or ecological thought but ‘the ecological thought’. Even though we are here rejecting definitions, I would argue that this is an absolute definition (itself, therefore, oxymoronic) of ecological art. An ecological arts practice is about a way of being in the world, open to all its wonder and complexities, feeling rather than seeing, expanding rather than reducing. It has at its core a ‘praxic opening out’ to paraphrase Guattari. Nature, suggests Morton, is more an 18th century concept arising from the Picturesque than anything to do with the natural world. Nature is a machine, an ultimate defining, a controlling, shaping thing. Concepts of Mother Nature, Heidegger says and Morton reminds us ‘are based on sedentary agricultural societies with their ideas of possession and control’. These are perhaps exemplified by the landscapes of the landscape architect whose 300th year we are currently celebrating here in England: Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown who, literally, moved mountains (well, large hills anyway) to create perfect parkland and carefully painted pictures, creating ‘landscape’. His work defined what we have now come to think of as the ideal of beauty in the English landscape – an ideal recognised universally. Ultimately this is an objectification, and a class-based one at that, available only to the wealthiest. It’s worth noting however that these landscape were far more ‘ecological’ than almost any created today. Before the age of machines and fossil-fuel consuming devices designed to cut grass and shape flora, these landscapes were managed by grazing animals, primarily sheep and cattle, in an entirely self-sustaining agricultural system that links immediately back to our abandonment of the hunter-gathering existence several millennia earlier.

But I digress. Here’s what Morton says: 'The kind of environmentalist ideology that wishes that we had never started to think — ruthlessly immediate, aggressively masculine, ruggedly anti-intellectual, afraid of humour and irony — is dubious at best…The constant assertion that we’re “embedded” in a lifeworld is, paradoxically, a symptom of drastic separation…’He goes on: 'Thinking the ecological thought…involves becoming open, radically open — open forever, without the possibility of closing again. Studying art provides a platform, because the environment is partly a matter of perception. Art forms have something to tell us about the environment because they can make us question reality. Is the ecological thought thinking about ecology? Yes, and no. It is a thinking that is ecological, a contemplating that is a doing…This is what praxis means - action that is thoughtful and thought that is active.' (Morton 2010)Here’s the crux: ‘art and ecology’ cannot be about a thing, should not try to teach us a lesson. Rather, it is a thought, a contemplating, to paraphrase Morton, a doing.He goes on to say: ‘Ecology talks about areas of life that we find annoying, boring, and embarrassing. Art can help us, because it’s a place in our culture that deals with intensity, shame, abjection, and loss. It also deals with reality and unreality, being and seeming. If ecology is about radical coexistence, then we must challenge our sense of what is real and what is unreal, what counts as existent and what counts as nonexistent…Ecological art, and the ecologicness of all art isn’t just about something (trees, mountains, animals, pollution, and so forth). Ecological art is something, or maybe it does something. Art is ecological insofar as it is made from materials and exists in the world.’ (ibid)

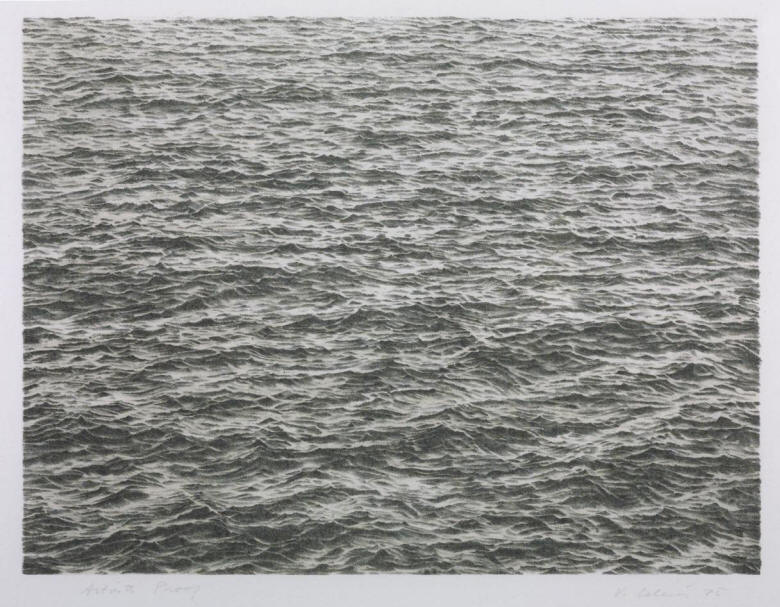

This is profound. What Morton explains, what we have known in our bones, in our hearts, for decades now is that art can say things by paying attention to and by being in the world. Not by overtly telling, not by simplification, not by trying to inform or even punish or excoriate, but by being. Art that is something, or that perhaps does something can be far more powerful as an exploration of the natural world, of our being and how we live in the world, than any quasi-political or animus-driven passionate re-telling of an environmental fact. It helps us understand that over the past forty or fifty years art relating to the natural world – ecological art if you will – has been truly a praxic opening-out, a re-embracing of wonder, of enchantment, of the power of the mind and the soul. A work that repairs a water shed, or that cleans the air may have a distinctly environmental materiality, but it nevertheless represents a re-thinking, a re-conceptualisation of what an artwork can be. Bark, or stones, or twigs, or feathers built into extraordinarily, profoundly beautiful structures, as if by a magical creature rather than a bumbling human, is also a redefinition. It is a reclamation of how we see the world around us, and how we honour and treasure it. A lithographic representation of the ocean (Vija Celmens, 1975 - top), a square of agitated water entirely without context, drawn in fine, extraordinary detail, is not a backward step towards representationalism or ultra-realism, but a spiritual meditation, a re-telling of a place to which we seem inexorably drawn.

A drawing, just the slightest abstraction of trees cut down and removed before their time, by Eva Hesse (Untitled, 1966); or Joseph Beuys’ influential and ambiguous Robbe (1981) (are we looking at a seal, or a human?) – are just two early works from this time of reimagined enchantment. And, picked just because they move me, a few more pieces: John Luther Adams’ ‘The Light that Fills the World’ (2005) (excerpt) Chris Drury, Carbon Sink 2012 Amy Sharrocks, The Museum of Water, 2015 Garry Fabian Miller, Fade into You (vii) July 2011 Andy Goldsworthy, Elm Leaves, 1978 Huang Jui-Chen, Map of Plants , Northern Taiwan 2015 Kate MccGwire, Perihelion 2014 (above) Tania Kovats, Only Blue 2010 Mark Farnington, Specimen 6, 2000 Kim Soon-im, Play 2015 Richard Long, A Line in the Himalayas 1975 Lauren Berkowitz, Sustenance 2010 (above) Alison Turnbull, Galapagos Blue 2009 Tea Mäkipää, Atlantis Wanäs 2007 (above) Berndnaut Smilde, Nimbus Dumont 2014 (above) Paula Hayes, Peanut Terrarium 2004 Barbara Roux, Flower Seed Moon 2012 Atefeh Kas, Looking for Animus 2014 Ri, Eung-woo, A Dragon River 2012 Ryu, Seung-gu, Untitled 2010 These are elegies, song cycles, full of wonderment, wondering, and humanity. And it’s not just visual artists, of course. Poets have written this way for centuries; more recently composers such as John Luther Adams Peter Maxwell Davies, Laurie Anderson, David Rothenberg have rejoiced in the splendour and magisterial, drawing directly on the world around them as the inspiration for their music. These and so many more tell stories of the world to us, abandoning modernism’s alienation now for almost as many years as modernism and the post-structuralists dominated our culture; it re-embraces unashamedly the world around us. This work is not a new voicing of our respect and love of the natural world, of course. The artists of the 19th century sublime: Turner, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Friedrich, Bierstadt, Shelley and others all shared wonder and enchantment. All spent hours, days, whole nights outdoors not merely observing or looking. For at least 40,000 years, humans have been expressing their desire to speak of the world around them through creative representation and expression. The 20th century was a mere aberration, a mis-caught breath of angst and fear. But the last forty years has seen a re-visiting; a yearning to reconnect to the place from which we have become so estranged and of which we feel suspicion and fear; a deep-felt desire to re-connect not with perhaps with Nature, but certainly with the ecological thought. A mourning for all we have lost.

Brady, J. (2016) Elemental: an arts and ecology reader. edn. Manchester: Gaia Project Press. Bateson, G. ([1972]) Steps to an ecology of mind. San Francisco,: Chandler Pub. Co.. Brown, A. () Art & ecology now. London: Thames & Hudson. Guattari, F., Pindar, I., and Sutton, P. (2011) The three ecologies. New York, NY: Continuum. Kovats, T., and Bradley, F. (2014) Drawing water. Edinburgh: Fruitmarket Gallery. Lovelock, J., and Margulis, L. (1973) Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: the gaia hypothesis. Tellus XXVI, pp.1-2. Morton, T. (2010) The ecological thought. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Morrison-Bell, C., Collier, M., Morrison-Bell, C., and Ross, J. (2013) Walk on. Sunderland: University of Sunderland Learning Development Services. Oxford Dictionaries (2016) [online] Available at <http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/ definition/english/ecology Waldrop, M M. (1992) Complexity. New York: Simon & Schuster.

5/12/17 |

|

|