|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

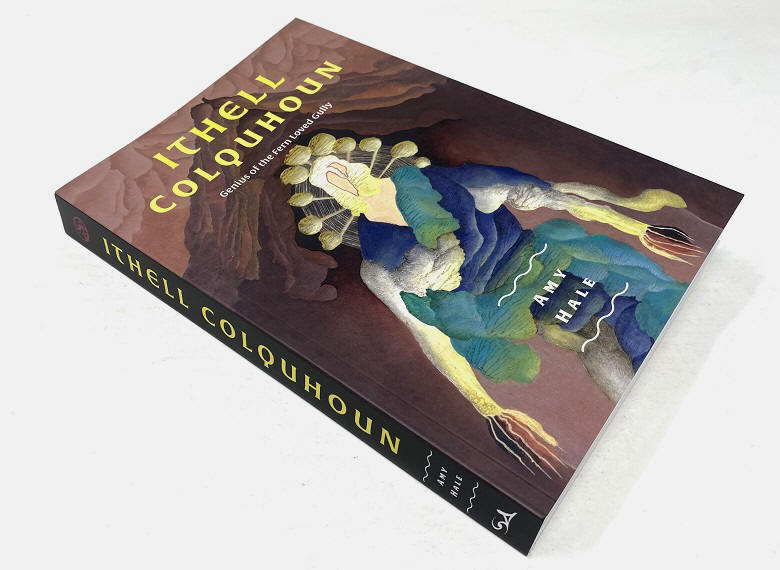

In this world but not of it Richard Shillitoe on Genius of the Fern Loved Gully: The Supersensual Life of Ithell Colquhoun, Artist and Occultist by Amy Hale.

It must be galling for an artist or writer to be remembered best for an event in their life rather than for any of their works. But for many years this was the fate of Ithell Colquhoun. Beyond a small number of admirers, the one thing that everyone knew is that she had been expelled from the London surrealist group in 1940 for refusing to compromise her interest in the occult. At last this is changing. Her paintings have started to appear regularly in exhibitions, her writings are now nearly all in print, and last year the Tate acquired her studio contents – roughly 4000 items - to be catalogued and conserved. Amy Hale’s book marks a major step forward in this process of increasing appreciation and understanding of her life and work. Hale’s discovery of Colquhoun was, for her, a transformative event. Her subsequent exploration of the archives – boxes of personal papers, folders of drawings and racks of paintings – all of which were almost completely unknown, deepened her entrancement still further. She describes her book as an ethno-biography, but as the dedication (“To all the women magicians, past, present and future. May our stories continue to be told.”) makes clear, it is also an homage. She believes Colquhoun to be “the most consequential, creative and committed female occultist of the twentieth century” (p.11) and she admires her for her achievements as a woman as much as she admires her art and her magic. She sees Colquhoun as an outsider: someone who was uncomfortable with the regimented colonial society into which she was born. Deprived of nurturing parental relationships as a child, brought up thousands of miles away from her mother and father, she found as an adult that she was uncomfortable with her sexuality and close personal relationships were often difficult. She felt a strong need to align herself with groups in the furtherance of her artistic or spiritual ambitions yet was uncomfortable with the personal demands and doctrinaire limitations that followed. Despite her personal charm and humour, she was not always an easy person to be around. Nor, frequently, was she comfortable within herself. Hale deals sympathetically with this: she has empathy for the predicament of a gifted, strong minded and independent woman who was frequently surrounded by men with consuming egos and had to fight for her voice to be heard. Genius of the Fern Loved Gully is not the first book on Colquhoun. The first was Eric Ratcliffe’s Ithell Colquhoun: the Versatile Surrealist which appeared in 2007. Age, infirmity and the inaccessibility of archived material all worked against him. To bring his book to fruition at all was an achievement, but the copy editing was selective: to cite just a couple of examples, one painting was illustrated twice with different titles and another was printed upside down. To my surprise, in all the reviews I have read, nobody seems to have noticed. My own Magician Born of Nature came out in 2010 but we have had to wait for over thirty years since Colquhoun’s death for Hale to do Colquhoun full justice. Rather than treat her subject chronologically, Hale adopts a thematic approach: a chapter on her childhood and adolescence leads to three major sections – surrealism, Celticism and occultism, followed by a short concluding chapter on her legacy. In truth, the handling often is chronological, otherwise there would be repetition and difficulties in dealing with Colquhoun’s development over time. By and large the arrangement works well, although accommodating everything within the tripartite structure is not always a frictionless fit.

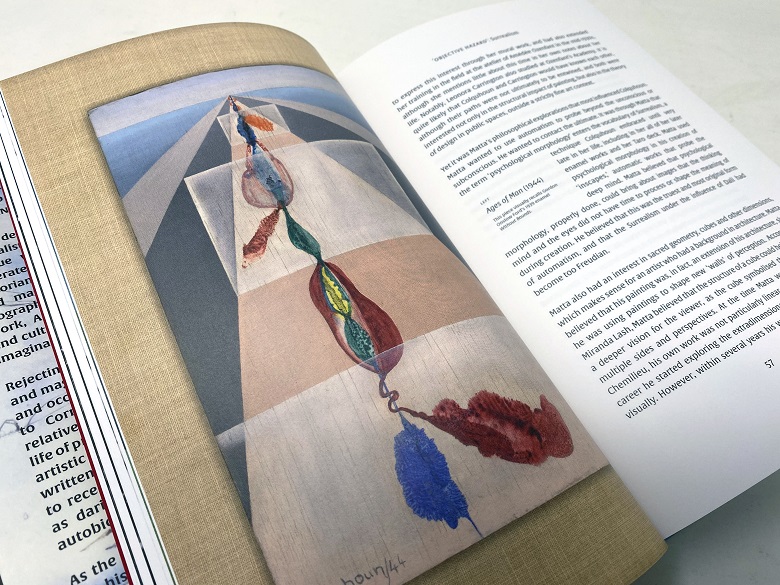

Surrealism Conventionally, Colquhoun has been understood as a surrealist artist who had an interest in the occult. To Hale, the reverse is true: she was an occultist for whom surrealism was one lens through which she focused her occult vision. Surrealism challenged the conventional view of reality and it questioned the illusory nature of every-day certainties. It fitted perfectly with Colquhoun’s magical outlook. Her stormy relationship with the Surrealist Group in England, which did not stop with her exclusion but continued following her short-lived marriage to Toni del Renzio (what on earth was she thinking of in marrying this charmer?), is the most researched aspect of Colquhoun’s career, probably because it falls squarely within the category of Art History and is therefore Respectable. In contrast with her negative experiences in England, the time Colquhoun spent with a group of continental surrealists during her short stay at Chemillieu in France in the summer of 1939 had significant and lasting benefits. During her discussions with Roberto Matta and Gordon Onslow Ford on the subject of automatism, she absorbed the concept of psycho-morphology: painting without conscious control that in some mystical way allows the artist to connect with nature and natural forces, not merely her personal unconscious. This must have been one of the key encounters of her life. It remains barely known, but Hale treats it with the importance it deserves.

Celticism Hale’s early research interest was on contemporary Celtic identities in Cornwall, so she is particularly strong on the social, political and cultural environment in which Colquhoun chose to spend the major part of her adult life. She is alert, also, to the discrepancy between the Cornwall of popular imagination and the often very different reality. Colquhoun came to see the landscape of Cornwall as a source of sacred experiences. (Hales’ title, Genius of the Fern Loved Gully, is taken from Colquhoun’s paean to the Genius Loci of Lamorna, the lush valley where she first lived in Cornwall.) Megaliths, holy wells, ancient churches, caves or suggestively shaped natural rocks were all places where earth energies flow to the surface and can serve as conduits or portals to other dimensions. In her writings this affinity with the earth is seen most notably in her book, The Living Stones: Cornwall (1957) but just as acutely in little-known essays, including ones on the Celtic wisdom tradition, Cornish crosses and those that record her visits to places of mystical significance. Everyone who knows the book loves The Living Stones but Hale provides the only detailed critique I have seen of its slightly earlier companion piece The Crying of the Wind: Ireland (1955). She shows that it is an altogether darker book in which Colquhoun, by turn “effusive and grumpy” (p. 133), displays some rather outmoded social attitudes. Hale demonstrates how Colquhoun’s pursuit of Celtic spirituality crystallised into her joining a number of societies which placed emphasis on the spiritual qualities of the land and promoted closer relationships with natural energies. In her discussion, Hale introduces us to fringe Catholicism, British natural wisdom, pan Celtic nationalism, mythic genealogy and the transmission of ancient mysteries. And here we have the makings of a potential problem. Genius of the Fern Loved Gully will attract a wide readership. Whilst some will be familiar with organisations such as The Universal Bond, The Fellowship of Isis and The Golden Section Order, others will not. Some of the cast of characters, such as WB Yeats or Robert Graves will be known by most, but it is much less likely that figures such as William Bernard Crow or Jean-Pierre Danyel will be familiar names to many readers, except to those with the appropriate spiritual interests. Equally, whilst some will be thoroughly conversant with the differences between the Breton Goursez, the Cornish Gorseth and the Welsh Gorsedd, can spell An Druidh Uileach Braithreachas without checking, and understand the reasons why the Universal Bond split into factions, they may know little about key surrealist figures such as Eduard Mesens or Roland Penrose. The problem is: what is the level of detail that the book should include? Too much, and readers may become lost in the complexities of unfamiliar subject matter; too little and the reader feels short-changed, or the topic itself may be trivialised. Fortunately, in a field where factional and doctrinal disputes are common and often viciously fought, Hale has a deft hand when dealing with intricacies and is adept at striking the right note. She is a reliable hierophant and this is a book to be savoured, not skated over.

Occultism The starting point for the section on the occult is Hale’s contention that Colquhoun’s art and writing “constitute the working record of a dedicated practitioner and theorist” (p.166). Colquhoun always self-identified as an animist. Whilst not disagreeing with the importance of animism, Hale suggests that Perennialism was the spine that provided the supportive structure for Colquhoun’s spiritual researches. That is, the belief in a single ancient wisdom tradition that appears in fragmented form in all the religions of East and West. Colquhoun’s search for these surviving fragments took her to many sources, including alchemy, Tantra, the Qabalah, heterodox Christianity and the sacred feminine. The chapter contains scholarly sections on such topics as the fourth dimension and occult geometry. It details the central importance to Colquhoun of the Golden Dawn’s teachings on the spiritual properties of colours. This led eventually to one of Colquhoun’s crowning achievements, the set of tarot cards she designed in 1977. This is an abstract, not a functional, deck but by stripping it of its visual symbolism she was able to concentrate on the occult significance of the colours and the elemental associations of each card. I think, however, that when Hale writes of Colquhoun’s “essays on the conventional trump cards” (p.260) that these were written by Tamara Bourkhoun and circulated to members of the Order of the Pyramid and Sphinx: Colquhoun’s own notes have not been published and are privately owned. The chapter also includes discussions of Colquhoun’s knowledge of such occultists as Crowley and Spare, the work of John Foster Case and on the relationship between Gerald Gardner and Cecil Williamson. It has lengthy analyses of Colquhoun’s novel Goose of Hermogenes (1961) and her later biography of MacGregor Mathers, Sword of Wisdom (1975). Hale leads the reader into recondite areas, such as sex magic and the unification of male with female - “an essential precondition of returning to the divine state that is our birthright” (p.188). Here Colquhoun asks challenging but seldom asked questions: is the conjunction to take place at the physical or the etheric level? Is it desirable that one’s partner be of the same sex? Perhaps engaging with one’s own animus/anima makes an acceptable or even superior alternative? Hale does not reach a settled conclusion but then, neither probably did Colquhoun. The whole chapter is a tour de force of erudition, but it is surely a misjudgment to allow a single chapter to take up nearly half of the total text of the book. Notwithstanding this, in immersing herself with the material on which much of it is based, Hale must have spent weeks underground in the archives at Tate Britain. So much so that one worries for her vitamin D levels. Just about the only thing I can usefully add to her knowledge of the archives is the identity of “Terence” (p. 235). He was Terence Day, the brother of Daphne Day, one of the members of the Order of the Pyramid and Sphinx and Tamara Bourkoun’s landlady from 1968.

Legacy “Legacy”, the final chapter, starts with a melancholic, elegiac tone. Hale regrets the fact of a woman sliding into old age and dependency and she mourns for the books that she did not write and the knowledge that died with her. But she finds reasons for hope. She points out that there is a greater appreciation nowadays that a truly metamorphic esoteric art can exist, not merely an art that uses the apparatus and imagery of magic. Hale notes that Colquhoun’s automatic practices have been especially influential in the recent work of Linder Sterling who combines automatism with found photographs and who has pursued the idea of a mantic ballet. And she discusses the collaborative Ancient Scent project in which artists, writers and magicians in West Cornwall came together to weave art, ceremony and automatism. The first public event organised by this group took place at Lamorna village hall, just a few yards from the site where Colquhoun’s Vow Cave studio once stood. Many of the talks and readings can be seen on the artcornwallvideo YouTube channel.

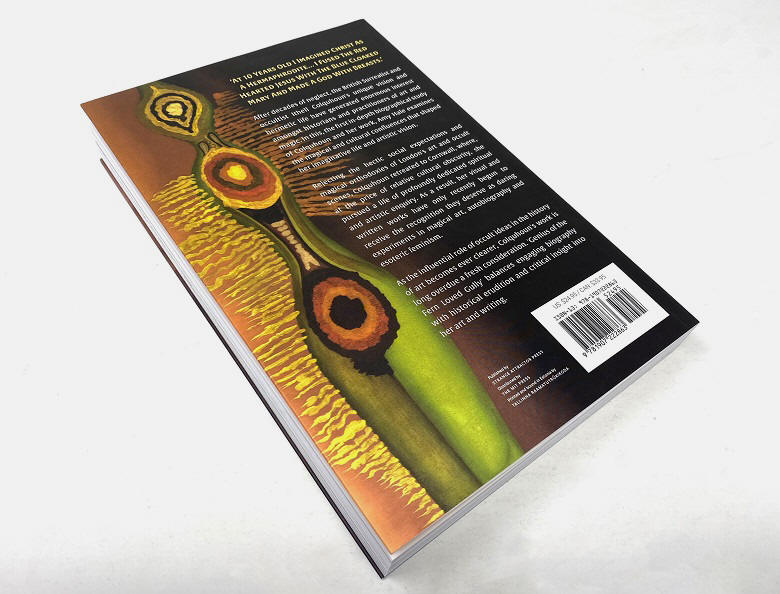

This book will be the standard work on Colquhoun for years to come. It will be extensively mined for information and inspiration. It contains some errors, but any differences that I have with Hale are, for the most part, minor ones of emphasis or interpretation. Here are some examples of where we differ. I disagree that the unpublished manuscript The Streams of St Bride is a short story (p.102). I think it is a straightforward factual itemisation of the sex lives of her neighbours, to which she added some occult speculations. Why she wrote it is a separate matter. Hale says that an early title for the novel I Saw Water was Unfaithfully Departed and suggests a reference to del Renzio is intended (p.147). The discarded title was actually The Unfaithful Departed (another reject was Lilies that Fester) making me think that it was more likely to be a reference to the post-mortem state of the characters. Finally, I think that Hale underestimates the importance of the watercolours of domestic and architectural scenes that Colquhoun painted during her Mediterranean travels in the 1930s. Individually they are of limited interest but the subject matter occupies the liminal zone between presence and absence, inner and outer, self and non-self: cumulatively they give an early indication of her fascination with transformation. The book is printed in the attractive Alverata typeface and has been well designed. High quality colour illustrations, together with many previously unseen black and white photographs of the artist taken throughout her life, are distributed within the text. I would have liked space to have been found for images of one or more of her botanical studies which, as Hale says, are “rich with the possibility of double entendre” (p.37) and for examples of the mythological and multi-figure compositions of the 1930s. After all, it was her traditional drawing and painting skills that led her tutors at the Slade to admire her “remarkable gifts” and to describe her as one of the most gifted students of her generation. No doubt budget was a constraint and because rapacious photo-agencies work against scholarship, difficult choices had to be made. But it is a timely reminder: how long will we have to wait for a catalogue raisonné? Two important events occurred whilst the book was close to publication. One was the appearance of Medea’s Charms, by Peter Owen Publishers. This anthology of Colquhoun’s shorter writings includes many of the poems, essays and fictional pieces that Hale cites as unpublished, so they are now easily available. The second is that the carousel that is Colquhoun’s copyright took a further spin when Tate acquired the studio contents. It is not surprising, therefore, that some of the attributions in the credits have not quite caught up. If history is anything to go by I don’t suppose anyone (except me) will notice, or anyone (including me) will care very much, such is the power of Colquhoun’s vision to captivate and enthral and of this book to illuminate that vision.

Genius of the Fern Loved Gully: The Supersensual Life of Ithell Colquhoun, Artist and Occultist by Amy Hale. Strange Attractor Press 2020. ISBN: 9781907222863 http://strangeattractor.co.uk/shoppe/ithell-colquhoun/ http://www.ithellcolquhoun.co.uk/ https://www.peterowen.com/shop/medeas-charms-ithell-colquhoun/ |

|

|