|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Folk in Cornwall: music and musicians of the 60s revival Marking its tenth anniversary, an excerpt from the 2013 book by Rupert White

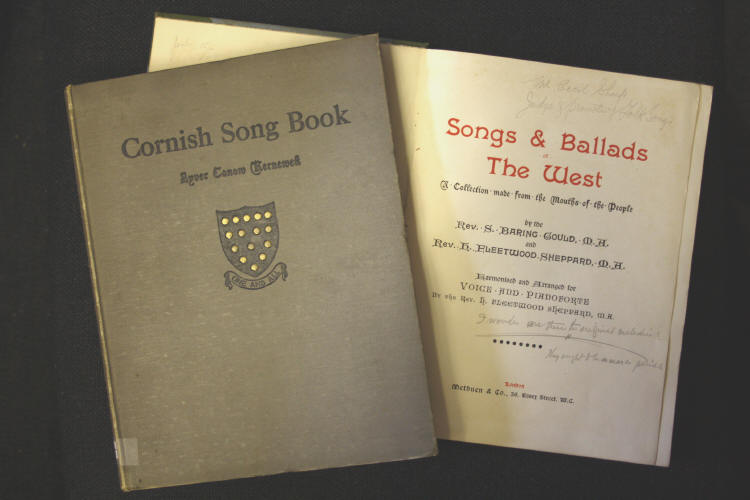

Folk music, in its various forms, has always existed. However the term only started being used in the way we would understand it now during the 1800’s, as a result of an emerging post-Enlightenment interest in folklore. Foremost amongst the early folklorists were pioneers like The Brothers Grimm, who collected and recorded folk tales that were part of a German oral story-telling tradition. Across Europe others were inspired by their example and in Cornwall publications by Robert Hunt (‘Popular Romances of the West of England’) and William Bottrell (‘Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall’) followed in 1865 and 1870 respectively. Folk songs were collected in much the same way, and one of the first and most celebrated of all the British song collectors lived in Lew Trenchard on the edge of Dartmoor, close to the Cornwall-Devon boundary. Best known by many as the writer of the hymn ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’, his name was Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould. Baring-Gould was both parson and squire of Lew Trenchard, and was prolific in many senses of the word: he was an author as well as the father - with his much younger wife - of 17 children. His ‘Songs and Ballads of the West’ was first published in 1889, and it is a compilation of musical scores for more than 100 songs collected in Devon and Cornwall. Baring-Gould and his collaborators are known to have travelled across the region in search of ‘old men’ singers over a period of about 10 years. Amongst the better known Cornish music in the collection is ‘Sweet Nightingale’; sent by an ‘E.F Stevens, Esq of the Terrace, St Ives’ and a version of the Helston ‘Hal-an-Tow’. Baring-Gould explains that as the Cornish language died out and became incomprehensible in the 18th Century, English words were grafted onto many preexisting Cornish tunes. So, as is typical of many traditional Cornish songs, whilst the lyrics to Sweet Nightingale were written and sung in London in the 1700’s, the tune is uniquely Cornish: one of several ‘melodies that probably had accompanied words in the old Cornish tongue in former times’. Davey 2007. The book is dedicated to one of Baring-Gould’s friends, Mr Daniel Radford who, according to the introduction ‘…knew that a number of traditional songs and ballads still floated about, and saw clearly that unless these were at once collected they would be lost irretrievably...’ In explaining why the songs were at risk, Sabine-Gould refers obliquely to the advance of industrialization ‘The purely agricultural districts are most auriferous. In manufacturing counties modern music has driven out the traditional folk melodies’. Importantly, he also mentions religious music: ‘Nowadays, domestic servants sing nothing but hymns…’ and Methodism: ‘One of my old singers, James Oliver, was the son of very strict Wesleyans. When he was a boy, he was allowed to hear no music save psalm and hymn tunes.

First editions of two of the earliest collections of Cornish folk music

The song-collector’s comments about Methodism were echoed by Ralph Dunstan writing in the Cornish Song Book of 1929: ‘With the great Wesley Revival a reaction set in against secular songs, and hymns and Christmas Carols took the place of ‘the Devil’s music’’ Folk singer Brenda Wootton - who, coincidentally, chose a faintly satanic image as the emblem for her folk-club - expressed a similar view nearly 100 years later when she compared folk music in Brittany to that in Cornwall: ‘Their music and dance is very strong and wild (of course, Charles Wesley didn’t come and save them with his hymns – consequently killing off all the natural local music as in our case). Cornish Review Spring 1972. It is undoubtedly the case that for more than a century Methodism shaped much cultural activity in Cornwall, as well as creating significant new cultural forms. The most relevant example of the latter would be the ‘tea-treat’, comprising Sunday tea taken outdoors by whole communities and here described by Merv Davey: At the height of its popularity, the Tea Treat involved a procession (or Furry Dance) through the village lead by the local band and decorated with various banners of the organisations involved such as the Band of Hope. Some tea-treats incorporated older folk customs, such as the Snail Creep dance: The Snail Creep…involved a long procession of couples following a band, led by two people holding up branches: the tentacles of the snail. A feature of the custom was the large number of people typically involved, one event in Bugle recorded as many as 600 adults and 350 children participating. Dancing was therefore a feature of many tea-treats, but the music played tended to be religious in content: typically Wesleyan hymns, or marches ‘which could be played slowly so that the children and old people could keep up.’(Dunstan) And the brass bands and male voice choirs which became increasingly popular in Cornwall at the turn of the century, evolved out of this same context. Inevitably they initially retained much of the same repertoire. In 1890 in an attempt to take traditional folk music to new, larger audiences Sabine Baring-Gould organised for a concert party largely made up of his own family members to visit venues in towns across the South-west. But in fact it was Cecil Sharp, who in founding the Folk Song Society (later the English Folk Dance and Song Society or EFDSS) in 1898, probably did most to organise and promote traditional folk song across England as a whole.

Gorsedd 1929, Carn Brea. Initiated in 1928, and following a surge of interest in the Cornish Language, the Gorsedd was the most visible manifestation of the ‘Cornish Revival’ of the 20s and 30s

Sharp, who was based in London but involved with extensive song-collecting himself (particularly in Somerset and the Appalachians in the U.S.), visited Baring-Gould in Devon several times in 1904 and 1905. These visits culminated in the revised and final edition of Songs of the West and in the book English Folk Songs for Schools which he produced in collaboration with Baring-Gould in 1906. In the same year Sharp dedicated his English Folk Song - Some Conclusions to Baring-Gould. Sharp went on to visit Cornwall once in 1913 and twice in 1914 towards the end of his own period of song-collecting. His engagement with the region was in many ways cursory, however, and he has been criticised in some quarters for ignoring Cornwall’s Celticity. This was true of the EFDSS as a whole which, even via its Cornish branch, had a tendency to promote the Morris dances of the Midlands rather than explore more local traditions (Davey 2012). Other song-collectors are also known to have been active in Cornwall in the early part of the 20th century. These included George Gardiner and an American by the name of James Madison Carpenter who in 1931 made recordings using a wax cylinder. The 19th century interest in folklore had led to a fully-fledged ‘Cornish Revival’ which ran parallel to the activities of the song-collectors, and was supportive of their efforts. In 1904 Henry Jenner, having spent many years working in the British Museum, wrote ‘Handbook of the Cornish Language’, and successfully applied to the Celtic Congress for Cornwall to be accepted as a Celtic Nation. As well as setting up the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies in 1924, other revivalists like Robert Morton Nance championed symbols of Cornish identity, including tartan and the black and white cross of the St Piran flag. In this transformative prewar period, the Old Cornwall Societies were instrumental in reviving the ‘Crying the Neck’ harvest ceremony and the ‘Golowan’ bonfires. Then 1928 saw the first Cornish Gorsedd (or College of Bards) (see picture). The event included a song written by Morton Nance, which was published the following year in Ralph Dunstan’s ‘The Cornish Song Book’. The book contains a collection of around 150 songs, some collected personally by the author, with others taken from the ‘Old Cornwall’ journal. It includes a separate section of carols including the much-loved ‘The Holly and The Ivy’. After the war, in 1951, Peter Kennedy worked with local singer Charlie Bate, to make a cine film of the ‘Obby ‘Oss in Padstow, which was released in 1953. Kennedy’s father was then director of the EFDSS, and his collaborator on the Padstow project the influential American song collector Alan Lomax, who had recently moved to London.

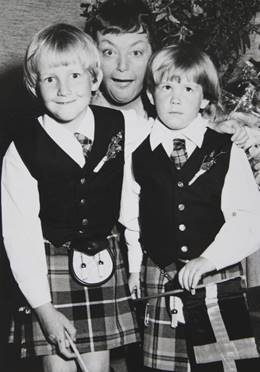

Brenda Wootton and her grandchildren, Davy and Jan, backstage in the early 1980’s. Both boys are wearing Cornish tartan and carrying St Piran flags, symbols of the Cornwall which Brenda helped popularise. They called Brenda ‘Damawyn’ or grandmother.

The narration, provided by Bate, features the words to the Padstow May Day Song and the film, as well having colourful footage of the pageant itself, includes a remarkable black and white sequence of dancers in The Golden Lion the night before (see photo). Kennedy went on to collect folk song recordings from all over the British Isles to feature on his BBC radio programme ‘As I roved out’. In 1956 he visited the Isles of Scilly, and on the mainland recorded Cadgwith fishermen, the Matthew Brothers of Logan Rock, and ensembles such as the ‘Truro Wassail Bowl Singers’. He also obtained material, including Cornish language songs, from the ‘Skinners Bottom Glee Singers’. Much of this music was printed later in the Cornish section of his influential compendium ‘Folk Songs of Britain and Ireland’ in 1975, some of it also appearing in ‘Canow Kernow’, by composer Inglis Gundry (1966). The activities of the folklorists, folk-song collectors and revivalists in the first half of the Twentieth Century came at a time of increasing financial hardship. Cornwall’s mining industry had collapsed - prompting mass migration - and helped by investment by the Great Western Railway, a more modest economy based on tourism was taking its place. This fledgling industry picked up in the period after the Second World War, as more and more people bought cars. At the time swing or dance bands and solo singers like Doris Day, Frank Sinatra and Vera Lynn dominated the British airwaves and singles charts.

Dancers in The Golden Lion, Padstow the night before May Day, 1951. One is the ‘Oss’, and the other the ‘teaser’. A still from ‘Oss Oss Wee Oss.’

Then suddenly in the 1960’s, coinciding with Cornwall’s increased popularity as a tourist destination, folk music went mainstream. No longer the preserve of the folklorist or musicologist, it was reinvented and became a genre within popular music. Partly due to the evangelizing efforts of Cecil Sharp’s EFDSS, traditional folk song and folk dance were taught in schools in the post-war period and were often featured on the radio. Both helped create an audience receptive to folk. But in the UK it was really the presence of American folk, skiffle, jazz and blues that fuelled the surge in popularity of folk music at the time. It was a period in history in which vibrant and distinctive new forms of youth culture emerged, many of them borrowing ideas and imagery from the U.S. So it was that in the early 60’s, young beatniks ‘on the road’ came to Cornwall and brought their guitars and their love of American folk and blues music with them. This American music was originally music of the fields. It spoke of a simple life: of God, farming and the railway and, though estranged from its origins, seemed to find a natural home in this relatively remote and unspoilt part of the South West of the UK. Living in tents, benders, caravans and beach shelters, beatnik musicians like Clive Palmer, Wizz Jones, John the Fish, Ralph McTell, Michael Chapman and Donovan came to adopt Cornwall as their spiritual or actual home. Although initially reviled, and seen as a threat to the tourist economy, their presence, alongside other more local musicians, eventually produced an unusually lively folk-scene. The folk-scene, as it developed, became an intimately interwoven community, not unlike the artist-colonies Cornwall is already well known for. For those that were involved, music-making and socialising were one and the same thing. Guitarist Pete Berryman has described it as ‘a series of circles, or families with the immediate local family based around the clubs in St Buryan and Mitchell and a larger, overlapping, family involving performers on the wider British club circuit’. Davey 2012. As an especially creative family, the folk scene in Cornwall produced more than 20 albums of folk music that are still enjoyed today. These albums include some of the most transcendental (COB), popular (Ralph McTell & Donovan), technically accomplished (Michael Chapman, Wizz Jones and Pete Stanley) and Cornish (Brenda Wootton) folk records of the 20th Century.

One of the first albums of Bluegrass ever recorded by UK-based musicians. The incongruous cover photo, evocative of the Wild West, was taken in Holywell Bay, Cornwall.

My book ‘Folk in Cornwall’ is an attempt to describe the context in which those records were made for those, like myself, that were not actually there. I’m indebted to all those who were, who contributed their recollections with such enthusiasm and candour. What has emerged, is I hope, a collective memory of a very particular, and uniquely interesting, moment in time.

'Folk in Cornwall' is available on Amazon and Waterstones. |

|

|