|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Landscape Painters Anonymous Simon Bayliss on painting 'en plein air' in 2015. First given as a talk at CAST Helston.

I’m a landscape painter, but it wasn’t always so. Last year I experienced an artist’s block and slipped into painting en plein air for instant gratification, but didn’t realise it would be so seductive: working like this is bliss. I prefer it when the weather is fine, and not too windy. I like to abandon myself to rolling panoramas across valleys, with distant views delineated by patchwork farmland, where I can feel emotionally connected to elemental nature. I bet if you joined me you’d also lose your inhibitions and express yourself more freely. But the transient bliss of plein air painting can leave me cold. Sometimes I come down the hill wondering whether it is undoing years of art education. It can feel as though the immediacy and ease of painting the landscape is erasing enlightening cultural experiences, dampening the studio voice that is otherwise scheming and contextualising. Perhaps this is okay, but why does the act of landscape painting now seem provincial, peripheral, amateurish and traditional? How can one transcend the context of leisure painting and tourist art through rendering the hills of Penwith in watercolours, with light washes and traditional techniques? The Cornish landscape is a dangerous tonic for unchecked self-expression. Remote and picturesque[1] views are just too easy to find.

Unlike place, landscape can only be seen from a distance, as a backdrop for the experience of viewing. Landscape is an aesthetic experience, yet place is an understanding formed through a long-standing engagement with a location or area. Awareness of place involves a complex network of experiences and memories, such as knowing the back roads from A to B, confident reversing on country lanes, uncanny encounters, an understanding of weather patterns, the local building vernacular, and the best tide and wind direction for particular surf spots and so on. Artists who are engaging with their locale in more holistic or challenging ways may argue that the role of landscape should not to lend form to a sense of regional identity. Social, agricultural and ecological reality is complex and fluid, far removed from the nostalgic projections of the tourist industry and the work of artists who represent Cornwall as a cultural anachronism. One may argue that it is only by taking into account the human, social and environmental aspects within a continuously changing, globally connected world, that landscape can be a mode of cultural reflection, rather than a reminder of a supposedly purer past. Is this possible in painting?

Attempting to expose the social and economic realities of place in paint would be a virtuous pursuit, however it could also detract from the kind of connection with nature I, and many others, seek – the addictive, blissful, and assimilating feeling. When painting en plein air, it is easy to become serenely oblivious to modern human infrastructure. It may feel comfortable painting the bell tower of a distant church, but telegraph poles, farm machinery and phone masts, dissolve and become superfluous. Perhaps this is because they symbolise the reality one is momentarily seeking to transcend, or perhaps because they are too difficult to paint, at least in shorthand. On a recent group painting trip to Carn Brea, everyone (including myself) largely ignored Camborne in favour of painting the surrounding fields. Was this because rendering the housing estates and industrial parks would be too fiddly and time-consuming, or because they are less attractive to the eye, or because they don’t fit with collective notions of what landscape painting should be? The images we produced depict panoramic expanses, yet they lack historic and economic realities of the nearest towns, where unemployment and social deprivation are well-known issues. An alternative to feeling guilty about this is to consider outdoor painting as a catalyst for recording vibrations of the inner-life of oneself. Painting en plein air offers an opportunity to address some of the formal aspects of picture making while acting as a mode of self-expression and meditation. The practice of recording ones intimate impressions of nature – clouds, light, topography and so on – is a vehicle for the individuality of one's observations and inner reality, in relation to place. For me landscape painting extends beyond observation and formal concerns, drawing on bodily sensations, humour, energy from the nervous system, time awareness, muscle-memory, an education in 20th and 21st century art, and the performative act of mark-making. Impressions of a landscape merge with traces of sensation, eroticism, animism, and mythology. However, I’m not here to promote romanticism and the virtuosity of the individual artist. I’m more concerned with how painting watercolours in Penwith can play a part in developing a progressive identity as an artist, in a region where landscape painting is rife. Identifying as a contemporary artist can feel out of place among rural communities. For example, when asked by non-artists what sort of art I make, I’m reluctant to mention painting landscapes, not wanting to evoke a cliché. I’ve often had to endure comments about the unique quality of light in Cornwall, and how fantastic it is for artists. This irritating idea made me assume, it was a myth; surely people should know that artists have more diverse and current concerns than natural phenomenon and working under a certain light. One can be as cynical, but the light in St Ives for example, is extraordinary, more lucid, creamy and turquoise.

I am also stimulated by the culture of landscape painting in the region. For me the tourist galleries of Devon and Cornwall represent a realm of guilty fascination; I'm attracted on one level because of the sense of collective regional identity, but simultaneously repelled by commercially driven attitudes. In St Ives, for example, where paintings are disseminated within the place they depict, they play a significant role in forming a sense of place, adhered to by the masses, for better or for worse. In particular I feel a connection to the practice of combining St Ives abstraction[2] with an emotional response to nature, a sensibility I would ascribe as peculiar to the South West. For me the challenge of forming an artistic identity is inextricably linked to my sense of place within the South West but also my experience with developing a gay identity in a non-urban area. It is easy to imagine that both aspiring artists and young non-heterosexuals who grow up in rural areas can feel out of synch with these communities, and therefore feel the need for spatial displacement and relocation. Rural areas and their inherent values can be inhibiting places for both non-normative sexuality and ambitious cultural activity, in contrast to urban areas, with established and progressive scenes and niche communities. Cities are therefore more likely to be liberating places to freely express alternative sexual or artistic desires and ambitions and more conducive to developing informed and unrestricted identities.

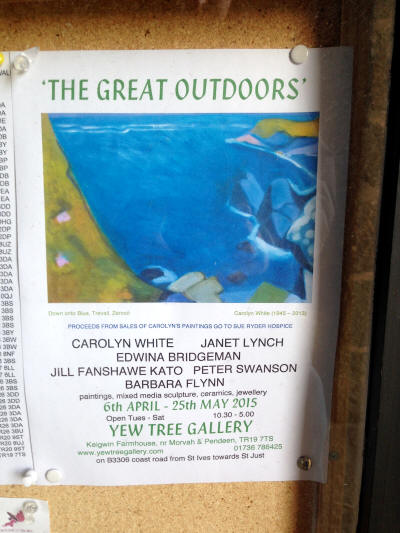

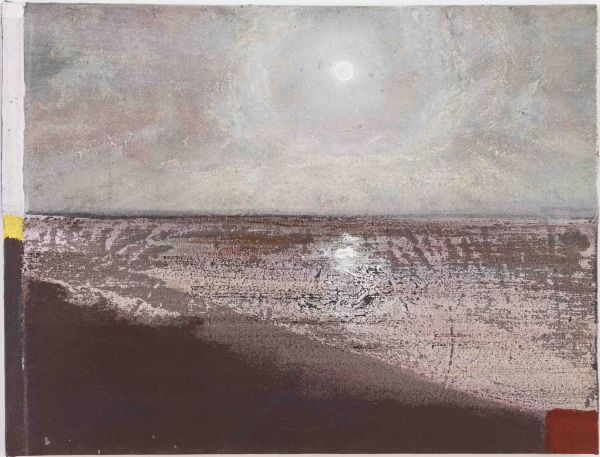

However, through growing up in small town in Devon and living in Cornwall, I have internalised what I feel is a system of values, aesthetics and strategies intrinsic to place. My approach is to negotiate and examine this through a critically aware practice. As an artist I feel as though my feet are in seemingly incongruous camps, with one stepping towards ideas-led practice, and the other rooted in regional aesthetic values. For me, this is a tentative position which is neither polemical nor acquiescent. At first, landscape painting felt like a bad habit or guilty pleasure that should remain closeted. Yet this has given way to concerns on how to make paintings about landscape which interrogate inherited notions of picturesque, or shift away from modernist tropes without compromising romantic inclinations or loyalty to a sense of regional aesthetics. Is it possible to draw on the most obvious and available resources in Cornwall and make it salient, even radical? Writing this is not a way to overcome my inclinations for landscape painting, but for catharsis, a way of consolidating thoughts, and to 'come out' as a landscape painter. Thankyou to Merlin James for image of 'Effet De Lune' (2011). Simon Bayliss is currently artist in residence at Hestercombe, Somerset. The culminating exhibition ‘Arcadia’ runs from 24th October 2015 – 28th February 2016 at Hestercombe Gallery.

[1] The term picturesque, which in its literal sense can be applied to much current landscape painting, was coined during the emerging Romantic sensibility of the 18th century, where it provided a conceptual framework, derived from landscape painting, through which to view and design actual landscapes. [2] A style or method of painting which echoes the prominent aesthetics, ideas and techniques developed by modernist artists associated with the wider field of international formalism, who were based in, or were linked to St Ives, such as Peter Lanyon, Barbra Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Patrick Heron. 6/10/15 |

|

|