|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

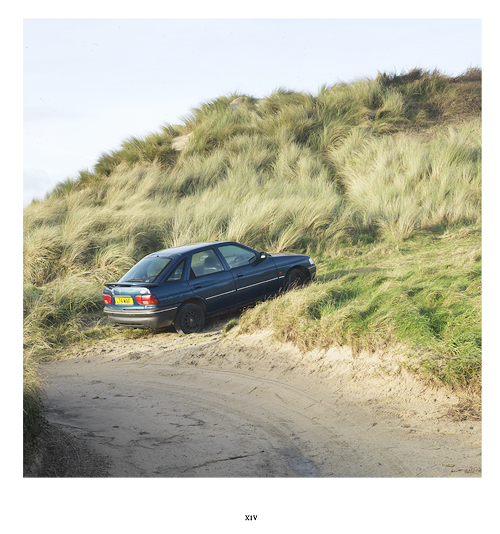

Tales of the Unexpected Megan Wakefield Tales of the Unexpected was a series of 'unofficial and unannounced' interventions in the landscape that took place as part of More Cornwall, and was recorded on the blog www.talesoftheunexpected.blogspot.com

In The Lure of the Local, her 1997 work on sense of place, Lucy Lippard states that: “Place specific art illuminates its location, rather than just occupying it.” While most of the images in Tales of the Unexpected do not directly refer to the history or peculiar identity of place, as individual fragments they contribute to an alternative mapping of the region. They avoid the Cornwall of unpeopled coastal landscapes, where the human trace has been erased because it risks corrupting an idyll.

This recalls Guy Debord’s Theory of the Derive (1956): “ In a derive one or

more persons during a certain period (…) let themselves be drawn by the

attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. The

element of chance is less determinant than one might think: from the

derive point of view cities have a psychogeographical relief, with

constant currents, fixed points and vortexes which strongly discourage

entry into or exit from certain zones.” Although Debord is theorizing about an urban context the creation of some of this work has necessitated a suburban or rural derive, the recording of which are spaces where human presence subverts the conception of a controlled space. Eccy is a summer postcard Cornish surfing beach, but Andy Hughes' photo (with accompanying text) records his encounter with an attempted suicide there (right). Rupert White has paused long enough in a commercial thoroughfare to mark out one white paving stone, as if this act were as legitimate as any other and Andy Whall’s short video Welcome, willkomen, bienvenue, benvenuti, bienvenido seems to show the artist enacting a Welcoming to travellers emerging from Penzance train station, as if to re-enchant the journey as a process of transition culminating in arrival. Their physical disembarkation should be remarked both by the traveler, but also by the ‘native’.

Works by Giles such as Water Figure and her Reclining Figure have echoes of contemporary ritual, but seem anachronistic because of their precedent in this ‘environmental’ art of the late 70s and early 80s. For me, the everyman/woman figure traced upon the land connotes the myth of the transmutation of the (female) body, spirit and land and sits uncomfortably with other images on the blog. It is also important to remember the specificity of the photographic form, however, and Giles’ montage Ploughed Compass makes far more effective use of the camera’s potential to record the play of the land, the arc of the sun and a human shadow.

Rupert White’s A Line

Made By Walking (below right) derived from Richard Long’s work, exposes the United

Downs landfill site as a selected place rather than a neutral space.

This is constructed land rather than landscape as a theatre for the mind

and senses. Of his work, Long said: “I like the way the degree of visibility and accessibility of my art is controlled by circumstance, and also the degree to which it can be either public or private, possessed or not possessed.” Richard Long, ‘Five, six, pick up sticks seven, eight, lay them straight’ (1980) Long’s work was exhibited as traces of an essentially private isolated and ephemeral activity, and unfortunately like a lot of “environmental” art it carries with it (intentionally or not) an air of earnest sincerity. The Internet has exponentially multiplied the exposure of the “private” in the “public” realm and so eroded the boundaries that exist between the two, letting humour slip between. Swiftie’s projections work well with this medium; the grotesque lip-cutting man at St Agnes, the spam email at Treliske, the messages to download porn on the screen of a local multiplex, a painted sign at Barnoon Cemetery reading 'Holy Water Overflow'. Swiftie bombs places with

intertextual jokes; the profane

Accessibility to the visible trace of a place is no longer so controlled or so limited. The works recorded on this blog may function as a collection or a continuum, which could provoke people to contribute their own interventions, expanding the concept beyond Cornwall.

This is an abridged version of an essay in a forthcoming book by the same name

|

|

|

bw3.jpg)