|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | archive |

|

In the shadows of artists: crafts-people of the St Ives colony Phil Whitfeld

There were, however, other craftsmen and women who had a profound impact on the artistic landscape of St Ives who are sadly, now, all but forgotten. They have disappeared; relegated to the wings of the stage that is St Ives; condemned to reside forever in the shadows of the artists. Included among the ranks of the artisans were metal workers Francis Cargeeg and Leslie Roskelly. Cargeeg, a Bard of the Cornish Gorsedd for whom he designed and crafted ceremonial regalia, was a gifted craftsman in beaten copper, a watercolourist and a contemporary and correspondent of writer, historian and craftsman Robert Morton-Nance, himself also a Grand Bard. Much of Cargeeg's work has been lost to private collections but examples can be found at Lanhydrock House and at The Guildhall in London. There was weaver Florence Welch who worked her hand loom from premises on The Wharf, itself the subject of a painting by L Richmond in 1931. So popular was her work that skilled local weavers were recruited to run the three looms that were crammed into the premises, and demand still often outstripped supply. Even Leach recognised the potential of Welch's shop as an outlet for his pots and a successful working relationship was established. Alice Moore (pictures above right & below left) was a celebrated embroiderer who had studied at The Art School in Penzance specialising in Industrial Design and Illumination. She later attended the Royal College of Needlework in South Kensington and was one of the first locals to be asked to join the Penwith Society established by Hepworth and Nicholson. She was also a member of the Red Rose Guild and in 1951 was invited to show at the Festival of Britain Embroidery Exhibition at St James' Palace. Her work was also included in the St Ives retrospective held at The Tate in 1985. Examples of her work can be found at Carbis Bay Church and at St Ia church residing alongside Hepworth's Mother and Child. Sadly her friend and contemporary Emma Harvey-Jones who specialised in embroidery and appliqué work has long been forgotten.

Hilda Quick was another local well-known engraver and was a student of Noel Rook at the Central School of Arts and Crafts who illustrated Prof. W L Renwick's edition of the works of Elizabethan writer Edmund Spencer. She was a respected ornithologist and wrote and produced engravings for many books. The Hilda Quick Hide still exists on St Agnes, Isles of Scilly where she settled in 1951. Another of Rook's pupils Guy Wordsall settled in St Ives in 1953 after further training with RJ Beedham. Among these craftsmen and artists there existed a network of mutual respect and support. Two of the most successful were brothers Robin and Dicon Nance. (Their father was the previously mentioned Robert Morton-Nance: a highly regarded writer and commentator who was almost single-handedly responsible for reviving the Cornish language). Robin, the eldest, was sent away to school at an early age but his parents were so appalled by the boy who returned that his younger siblings (there was also a younger sister, Phoebe, who would marry into the family of artist Dod Proctor) were home-tutored by Arthur Raleigh-Radford, a man as bohemian and flamboyant as his name suggests. A Cambridge graduate whose father was a collector of antiquities and fine furniture, he was later to become head of the British School in Rome. Dicon's son Johnny feels the rather isolating childhood experience of home-tutoring was an important factor in shaping his father's character. The lack of interaction with other children resulted in Dicon being painfully shy and self-effacing, almost invisible to those who did not know him. As an adult these traits were paramount in him never pursuing or receiving credit for his many achievements. Robin on the other hand was a master of social skills and it was this that later enabled him to become an established figure among the St Ives social and artistic community. Both boys, under the influence of their father, were fascinated by craft and making from an early age, but their grounding in practice took very different routes. On completing school Robin left Cornwall to train as a furniture maker with A. Romney Green (a leading light of the Arts and Crafts movement) at his workshops in Christchurch in Dorset, later returning to St Ives to establish a workshop of his own (see photo at bottom of page). While Robin's philosophy regarding craft was very much in line with Ruskin, Morris and the early Arts and Crafts practitioners, like many of his contempories Robin accepted that machinery could play a meaningful role in craft practice if utilised with skill and integrity. While the aesthetic of Robin's work referenced Arts and Crafts he was later to develop a style more akin to the clean, contemporary feel emanating from Scandinavia. Over a span of almost 40 years the business ceased trading only once when Robin enlisted for active service during the war. Dicon who had been apprenticed to Bernard Leach in his early twenties was a conscientious objector and spent the war collecting from inaccessible coves seaweed for agricultural purposes using an elaborate aerial ropeway/hoist of his own design. He joined Robin's business at the cessation of hostilities and upon Robin's return to St Ives. Although without formal training in woodworking he had skilled himself in a range of disciplines: engineering, carving, throwing, wood turning and chair making and he was later to became an assistant to Barbara Hepworth. According to Johnny he displayed a naive quality of originality "you wouldn't find him anywhere near a bandwagon let alone jumping on one. He taught me that there is virtue in being a perfectionist"

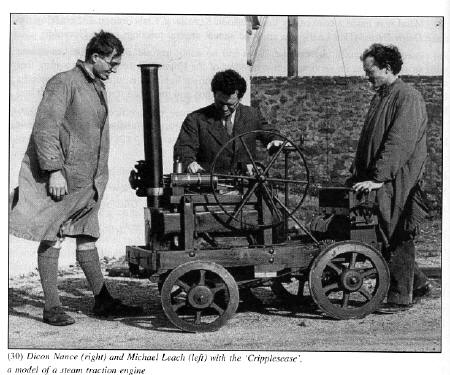

The design was later sold by David Leach to Woodley's of Newton Poppleford, and put into production. Now no longer in business, the wheel is made by a handful of firms in the US. Sadly Dicon received little or no recognition for his work and certainly no financial reward. While at the pottery he also designed, built and installed a small mill for crushing minerals for glazes run off the flow of the Stennack stream. The sad irony in this lack of recognition is that Dicon was Leach's son-in-law, having married daughter Eleanor and therefore brother-in-law to David who took much of the credit for his work. As teenagers David's younger brother Michael and Dicon built together a scale model of a working traction engine 'The Cripplesease' (picture below right). This was presented to Camborne Technical College in 1940 and resurfaced in Truro in the 1970's in the belief that it was Trevithick's original Puffing Billy. Lost again, it is believed to be still showing at rallies throughout the country but it's provenance now obscured or forgotten Dicon spent several years working in North Africa for the UN building and establishing potteries with Michael Cardew and Harry Davis, both Leach apprentices. He also visited Thailand where he designed and intro-duced a water carrying wheel barrow easily made in any village with the most basic tools and raw materials. He later returned to his brother's workshop once again where he designed and built a morticing machine to help speed up production of the ladder-back chairs which had become nationally in demand. This new machine working on a series of 'stops' produced identical and accurate components every time and negated the need for marking out. Leaving the business once again in 1959 Dicon became, alongside Dennis Mitchell and Terry Frost, an assistant to Barbara Hepworth at the Trewyn Studio. Employed for his skills as a carver and often working from only the simplest sketches he would produce sculptures that were completed and despatched in Hepworth's absence. According to Peter Davies' book 'After Trewyn' Dicon found his time there stressful. Hepworth, it seems, would brook no dissent and he subsequently felt that towards the end of her life he had played an undervalued, interpretive role, translating her scribbled drawings into sculptures for little or no credit. While much of this was necessitated by Hepworth's infirmity in her later years as well as her decision not to employ assistants that would be distracted by their own ambitions, Dicon questioned, according to Peter Davis, the validity of the artist's role particularly when the physical execution of the work often fell exclusively on the shoulders of craftsmen such as himself. Design historian Tanya Howard suggests this reaction confirmed his somewhat jaded view of fine art and its practitioners.

However Robin's ebullient nature ensured that he was far more involved with the artistic community both personally and professionally. He counted many as his friends and provided services by making bases for sculptures, frames for paintings and private commissions for individual items of furniture. Leach commissioned a three-legged stool, now owned by Johnny Nance, the legs of which he insisted were to be drawn with a blade in the traditional manner and not turned. The two families had been linked for many years and often worked on collaborative pieces. One successful joint venture was a series of coffee tables for which Leach would produce tiles to be inset in the top. These were sold through the Nance retail outlet on the Wharf and also nationally. Illustrating how these pieces are now regarded with an artistic rather than craft bias, several of these tables were sold through auction by Bonham's and yet in a ceramics sale rather than a furniture one - Robin's work playing both literally and metaphorically a supporting role. Robin also carried out similar projects with potters Harry and May Davis, both former Leach pupils but whose work is very much considered craft. The Nance business acted as framers for many of the St Ives painters and one who consistently used them was Ben Nicholson. A letter from Nicholson, to which I was given access, was sent from America to St Ives with a request for a new frame for a painting which was to be held at The Guggenheim, 'one with your special corners'. Where traditionally a picture frame has mitred corners, these frames, which appear to be peculiar to Nicholson, are simply butted together allowing a section of the timber's end grain to show at every corner. While the letter is undated we can assume that the incident probably occurred in the early 60's as the Guggenheim did not open until 1959. Robin also had connections with the Crysede Fabric Printing business run by Patrick Heron's father Tom. Robin's wife Marnie had moved to Cornwall to work for the business and met Robin while calling at the shop on the Wharf. To illustrate the standing that Nance Furniture developed during the post war period, they contributed to several major exhibitions including The Festival of Britain in 1951 - for which they received a commendation - and the following year were awarded a Diploma D'honore at the Mostra Mercato Internazionale dell' Artigianato in Florence. The business also exhibited with the Red Rose Guild of Craftsmen in 1954 and consistently sold work through the Craft Centre in Haymarket and at Dartington in Devon.

While being outraged (the St Ives Times and Echo suggests he was livid) Robin remained away from the controversy, but according to a family source this decision certainly made him question his relationship with the 'avant-garde'. It is still not clear how active he remained within the society, but he maintained his professional relationship with Nicholson. A 1951 edition of 'Cornish Review' quotes Robin as stating 'So often today we find evidence of the decay of British craftsmanship... so I venture to claim that Craftsmanship should be put on an equal footing with Art by our young intellectuals. I do not mean by this that I would like to see our workshops invaded by long bearded and woolly-minded aesthetes'. Maybe he was truly revealing his feelings towards the community by which he had so recently been snubbed. By 1960 the cultural and economic landscape of St Ives had changed forever. Previously the haunt of a wealthy clientele, changes in the Factories Act giving workers two weeks annual holiday helped to make St Ives the chosen destination for thousands of working class families. This major change in the demographic had a profound effect on the town and the businesses within it. Unlike their predecessors, these new holiday makers certainly did not have the financial capacity to support the numerous craft outlets active in the area. Over the following decade as the working classes moved in the upper and middle classes went in search of pastures new taking with them the money and the aesthetic sensibility so important to the survival of the artisans. Increasing ill health and the growing demands of trying to maintain both a workshop and a retail outlet influenced Robin's decision to retire from business. The shop which really had been a precursor to outlets such as Habitat and the Conran Shop was bought out by employees but as Robin saw it dumbed down to meet the economics and aesthetic wants of a working class clientele. The furniture workshop was taken over by Robin's final apprentice Peter Marshall, whose father Bill had been a principal thrower at the Leach Pottery. Robin himself went into semi-retirement and concentrated on boat building.

This is an updated and edited version of an original paper delivered at the 2008 International Design History Conference held at University College Falmouth (now Falmouth University). It was subsequently published as part of a book of selected papers both electronically and in hard copy. An edited version was also published by Magicalia Publishing (Good Woodworking magazine) the following year.

|

|

|

So

in it's treatment of St Ives, art history has celebrated the

intellectual, the romantic and the metaphysical, and yet the common-place

and the mundane, the craft that celebrates nothing more than its utility

and whose beauty is an intrinsic part of its function, has been

symbolically consigned to the workshop floor. A Leach pot may be

rhapsodised over with quasi-religious fervour, and yet serves no purpose

other than its sublime and divine existence. A bowl by Harry Davis or a

Nance chair on the other hand celebrates superb craftsmanship and practical utility... and therein lies its beauty.

So

in it's treatment of St Ives, art history has celebrated the

intellectual, the romantic and the metaphysical, and yet the common-place

and the mundane, the craft that celebrates nothing more than its utility

and whose beauty is an intrinsic part of its function, has been

symbolically consigned to the workshop floor. A Leach pot may be

rhapsodised over with quasi-religious fervour, and yet serves no purpose

other than its sublime and divine existence. A bowl by Harry Davis or a

Nance chair on the other hand celebrates superb craftsmanship and practical utility... and therein lies its beauty.