|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Silent Harmonies: The Art of Jeremy Annear Jane Hamilton

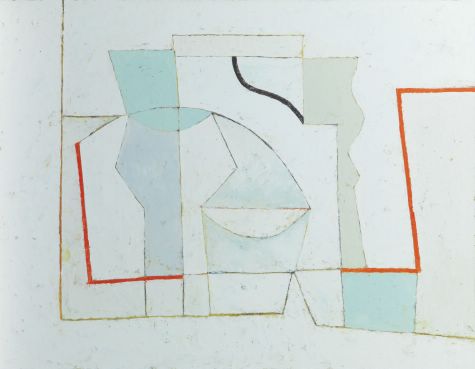

In the selection of work in the present exhibition at Messum's, certain titles are repeated on a number of occasions, some of them having now been used by Jeremy for a period of some years; titles such as Line Song, Silent Rhythms, Dawn Song and Maritime Blues. In these works musical rhythms merge with the distilled shapes of the Cornish landscape and, the artist explains, that while the same essential marks and forms may be found in the paintings comprising each series, there are numerous subtle shifts and transmutations taking place too, making each work a staging post on a continuing artistic journey.

His year as artist in residence at the Atelierhaus Verlag in Worpswede in the early 1990s further encouraged his field of artistic interests over international boundaries. During this period the work of the German artist Kurt Schwitters became particularly important to Annear, influencing a greater use of collage in his own work—a sense of which is still retained, even after the actual inclusion of different materials and found ephemera has been abandoned. But neither should the strength of the artist’s rootedness within the fruitful ground of west Cornwall—the home of Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Roger Hilton and Peter Lanyon to mention but a few—be underestimated. The Annear name is Cornish in origin and in previous interviews he has spoken of the goose-pimples that ran down his back when he first encountered modernist painting in St Ives when on holiday at the age of twelve or thirteen.

In the past, when Jeremy has been asked by his students at the various art colleges at which he has taught what his paintings were ‘about’, his reply—in an attempt to help a late-teenage audience identify with the work—was that his arrangement of shapes and forms on canvas was similar to the way in which they might arrange their things in their rooms. There is a moment during the course of such a process that one establishes a sense of ‘rightness’ and ‘wrongness’ about where the furniture is situated in relation to the walls and ceiling, and another moment, after some degree of experimentation and rearrangement, when one feels that a harmonious arrangement has been achieved. The analogy, however, can only be taken so far as the nature of the harmony that Annear seeks to achieve in his pictures is not a straightforward matter of aesthetics or decoration. ‘Decorative’ today often carries a pejorative meaning when used as a term in connection with a work of art, denoting something that addresses the viewer only on the level of pleasing the eye. As Annear is keen to emphasize, however, the act of decorating, of pattern making, is a fundamental part of human existence. Several visits to Australia in the early-1990s first brought the artist into contact with Aboriginal painting and this so-called ‘primitive’ art led him to consider the basic role that decoration often plays in ritual and religion. When Annear talks about achieving harmony and ‘rightness’ in his compositions, therefore, it is to do rather with the achievement of a deeper inner sense, perhaps better defined as ‘ease’.

Jeremy’s studio in the chapel’s former Sunday School is no less harmonious and achieves a powerful sense of calm, despite containing all the assorted accoutrements necessary for painting. As well as photographs of his wife and children, on one wall is a curious collection of postcards and prints: a photograph of the last Pope, a Virgin and Child by Titian, an Aboriginal painting, and the National Gallery’s painting of St Veronica with her veil—the bearer of the vera icon, the true image. On a high ledge in front of a semi-circular lunette are an assortment of bottles, pieces of driftwood and an old gas lamp—objects found in the vicinity of the chapel, along nearby beaches and on the Goonhilly Downs where he walks the dogs, Billy and Banjo, each morning. With the light behind them, these objects produce strong and pleasing shapes, both positive and negative, that certainly inspire some of the forms in the paintings. But there is no process of direct transcription within Annear’s artistic process. Despite the tradition of painting in the open air on the Penwith peninsular—started in the late-nineteenth century and advocated perhaps most famously by Stanhope Forbes when he settled in nearby Newlyn—Jeremy seldom draws or paints in front of a motif. For Annear, as for the great majority of Cornish modernists, landscape is not a scenic backdrop to be observed as if from an objective distance. A little like Peter Lanyon, who went so far as to take up hang-gliding and rock-climbing to gain new vantage points on the landscape, Annear is an active agent within the landscape, observing his surroundings at the start of each day as he walks and drives across the area.

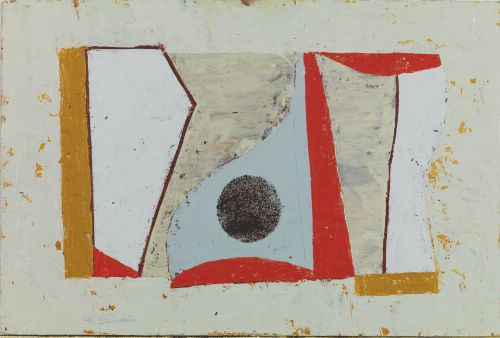

It is a country of eccentric angles and surprising viewpoints in which the sea can suddenly rise up in front of the car as it rounds a corner, appearing as a dazzling silver plane that sets all else into relief. Unlike his wife Judy, Jeremy is unlikely to try and capture the bleak magnificence and scale of the place. Instead, he will alight upon the curiosities of this landscape. Importantly for his colour-palette, the local stone is particularly rich in minerals and the pebbles on the local beaches are often shot through with the dark reds and greens of jasper and serpentine. Driftwood and other flotsam, lichens and mosses, are also likely to capture his attention, as are the unexpected reflections of the sky seen in rock-pools, which introduce a startling segment of deep blue into an otherwise monochromatic setting.

Despite his interest in the similarities between musical and artistic language, when Jeremy is working on a painting, he tends to do so in complete silence, carrying the rhythms of the day internally. When he taught periodically at the Dartington College of Arts in the 1970s, Annear was involved in founding a festival of performance art and there are still traces of the performance artist in his current painting practice. It is, however, a very controlled performance, and paint is applied with mantra-like concentration. He remains very conscious of his breathing, of his own physical movement around the studio and of the pace of his application of the paint—surface on surface on surface. Jeremy usually prepares his canvases with a dark earth colour like raw umber, working on top of this ground progressively in stages. There is therefore a process of effacement involved in the work; where there has been colour there is often now a dense white, deeply tactile surface. The resulting effect is reminiscent of the way in which the earth tones of medieval wall paintings often seep through the Protestant reformers’ layers of whitewash, although no reformer ever applied paint with such a degree of sensuality. For the viewer, this leads to the sense of the archaeology of the painted surface, a suggestion of something lying beneath and what otherwise might have been.

Annear’s paintings are not, therefore, uniformly flat modernist surfaces. Lines and forms seem to retreat behind one another, re-emerging at logical junctures elsewhere, creating a satisfying series of solid and transparent planes. The depth within the image is only implied, however; it is supplied by the viewer, whose participation is actively sought by the image. This is an art without illusionistic pretensions; less a window than a mirror, encouraging imaginative reverie on the part of the viewer. The decision as to when a painting is finished is as intuitive and organic as the rest of the process, but it sometimes comes after works have been left in the studio for a period of some months, and often when the artist has been on the point of making a change. The fact that he stops at just such a moment of ambiguity, when further change is still possible (surely a definition of life itself), means that the viewer is able to pick up and carry forward the creative process in the mind’s eye. The line can be taken onwards to the next logical point, just as one can improvise several tuneful conclusions to a melody, or partake in someone else’s thought processes and anticipate the end of a sentence.

Jeremy Annear was at Messum's Cork Street 18/03/2009 - 04/04/2009 images courtesy of the gallery |

|

|

Such

titles reflect Annear’s fascination with the synchronicity of art and

music, and with the ambiguity of language that can be used to describe

music and painting, as well as poetry. A line of music or verse has a

certain rhythm similar to the cut, meander or thrust of the lines in one

of Annear’s paintings. His work has inspired the poet Robert vas Dias

and there have been a number of fruitful collaborations with the

contemporary composer, Jim Aitchison, whose most recent work was

commissioned as a response to Rothko’s Seagram Murals and was performed

at Tate Modern to coincide with their retrospective of the artist’s work

earlier this year. These interests are indicative of Annear’s artistic

roots within a broad European modernism—one thinks of the similarities

with the interests of Klee and Kandinsky in particular.

Such

titles reflect Annear’s fascination with the synchronicity of art and

music, and with the ambiguity of language that can be used to describe

music and painting, as well as poetry. A line of music or verse has a

certain rhythm similar to the cut, meander or thrust of the lines in one

of Annear’s paintings. His work has inspired the poet Robert vas Dias

and there have been a number of fruitful collaborations with the

contemporary composer, Jim Aitchison, whose most recent work was

commissioned as a response to Rothko’s Seagram Murals and was performed

at Tate Modern to coincide with their retrospective of the artist’s work

earlier this year. These interests are indicative of Annear’s artistic

roots within a broad European modernism—one thinks of the similarities

with the interests of Klee and Kandinsky in particular.  Norbert

Lynton has discussed at some length another source of intrigue and

ambiguity in Annear’s work, namely the question of genre. Though

still-life elements are frequently discernable in the images, there is

often a distinctly earthy quality to the paintings too—perhaps derived

from the idiosyncratic colour palette used, the stone-like nature of

some of the surfaces or a pervasive organic quality that makes the

paintings feel anything but ‘still’. The inclusion of local place-names

in some of the titles, as well as certain other elements, points to the

work’s connectedness with the locality—but the connection is clearly not

a simple matter of resemblance. In this year’s show there are a couple

of paintings that feature the letters ‘PZ’, the letters typically found

on the boats local to the harbour of Penzance. The letters trigger

memories for the artist. In his early teens he met and became friendly

with the crew of a local pilchard-boat, who made a fuss of him and often

took him out fishing with them, sometimes allowing him to steer the boat

when they were occupied hauling in the nets. The crew would often sing

together in four-part harmony, occasionally singing in response to the

crews of other boats sailing within earshot across the expanses of the

sea at dead of night, making a deep impression on the young Annear.

Norbert

Lynton has discussed at some length another source of intrigue and

ambiguity in Annear’s work, namely the question of genre. Though

still-life elements are frequently discernable in the images, there is

often a distinctly earthy quality to the paintings too—perhaps derived

from the idiosyncratic colour palette used, the stone-like nature of

some of the surfaces or a pervasive organic quality that makes the

paintings feel anything but ‘still’. The inclusion of local place-names

in some of the titles, as well as certain other elements, points to the

work’s connectedness with the locality—but the connection is clearly not

a simple matter of resemblance. In this year’s show there are a couple

of paintings that feature the letters ‘PZ’, the letters typically found

on the boats local to the harbour of Penzance. The letters trigger

memories for the artist. In his early teens he met and became friendly

with the crew of a local pilchard-boat, who made a fuss of him and often

took him out fishing with them, sometimes allowing him to steer the boat

when they were occupied hauling in the nets. The crew would often sing

together in four-part harmony, occasionally singing in response to the

crews of other boats sailing within earshot across the expanses of the

sea at dead of night, making a deep impression on the young Annear. The

interiors of the Annears’ former Methodist chapel—once depicted in a

graphic work by John Piper and featured in Sir John Betjeman’s ‘First

and Last Loves’, the poet’s popular writings on architecture—contain

intriguing collections of African masks, Aboriginal artefacts,

distinctive pieces of modernist furniture and artworks by Keith Vaughan,

Maurice Cockrill and Prunella Clough. A piano sits at the centre of the

large upstairs sitting room and a number of antique accordions are

situated at accessible vantage points—not mere objets d’art, but

instruments that are played at family gatherings for the sheer joy of

music-making, when the roof is raised in a cacophony of song. These

sessions recall the former usage of the chapel and the Annear family’s

roots in the Christian Brethren, where hymn singing was traditionally

unaccompanied, the members of the congregation being instructed to find

their own harmonies within the dominant strain of the melody.

The

interiors of the Annears’ former Methodist chapel—once depicted in a

graphic work by John Piper and featured in Sir John Betjeman’s ‘First

and Last Loves’, the poet’s popular writings on architecture—contain

intriguing collections of African masks, Aboriginal artefacts,

distinctive pieces of modernist furniture and artworks by Keith Vaughan,

Maurice Cockrill and Prunella Clough. A piano sits at the centre of the

large upstairs sitting room and a number of antique accordions are

situated at accessible vantage points—not mere objets d’art, but

instruments that are played at family gatherings for the sheer joy of

music-making, when the roof is raised in a cacophony of song. These

sessions recall the former usage of the chapel and the Annear family’s

roots in the Christian Brethren, where hymn singing was traditionally

unaccompanied, the members of the congregation being instructed to find

their own harmonies within the dominant strain of the melody. The

dramatic landscape of the Lizard Peninsular and particularly the

Goonhilly Downs does not fit easily within any of the traditional

categories of the British Romantic landscape tradition. They are neither

‘beautiful’ in the classical sense of the word, and they are not

‘picturesque’ in the way that one might use the term in relation to

nearby coastal villages, made up of cottages with thatched roofs and

brightly coloured fishing boats pulled up onto the beaches. The Downs

are broad plains of heather, bracken and rough grass, populated by the

occasional Ayrshire cow and dominated by the huge geometric structures

of the Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station, where over sixty satellite

dishes point up into space. Now housing the unique Future World

attraction, Goonhilly was once responsible for sending and receiving

millions of telephone calls, television pictures and internet

connections around the globe. Not entirely inappropriately, given their

savannah-like appearance, a local camel farm proposes to offer

camel-safaris in the summer season across Goonhilly’s vast expanses.

The

dramatic landscape of the Lizard Peninsular and particularly the

Goonhilly Downs does not fit easily within any of the traditional

categories of the British Romantic landscape tradition. They are neither

‘beautiful’ in the classical sense of the word, and they are not

‘picturesque’ in the way that one might use the term in relation to

nearby coastal villages, made up of cottages with thatched roofs and

brightly coloured fishing boats pulled up onto the beaches. The Downs

are broad plains of heather, bracken and rough grass, populated by the

occasional Ayrshire cow and dominated by the huge geometric structures

of the Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station, where over sixty satellite

dishes point up into space. Now housing the unique Future World

attraction, Goonhilly was once responsible for sending and receiving

millions of telephone calls, television pictures and internet

connections around the globe. Not entirely inappropriately, given their

savannah-like appearance, a local camel farm proposes to offer

camel-safaris in the summer season across Goonhilly’s vast expanses.

These

fragments of the landscape may be carried home or retained in the memory

and they reappear in drawings executed later in the studio. Annear is a

great believer in the Surrealist practice of automatic drawing; drawing

as a means of opening the unconscious. He was involved in a Surrealist

festival in Exeter in the late-1960s, which was overseen by George Melly

and visited by Roland Penrose—itself a surreal happening. The event made

a deep impression and the drawings of Masson and Penrose Annear found

particularly impressive. Through automatic drawing, impressions and the

forms and shapes of objects collected on the beach reoccur in the

drawings, distilled, skewed and subtly changed, in the way in which a

day’s events can take on new and unexpected significance when they

reoccur later in our dreams.

These

fragments of the landscape may be carried home or retained in the memory

and they reappear in drawings executed later in the studio. Annear is a

great believer in the Surrealist practice of automatic drawing; drawing

as a means of opening the unconscious. He was involved in a Surrealist

festival in Exeter in the late-1960s, which was overseen by George Melly

and visited by Roland Penrose—itself a surreal happening. The event made

a deep impression and the drawings of Masson and Penrose Annear found

particularly impressive. Through automatic drawing, impressions and the

forms and shapes of objects collected on the beach reoccur in the

drawings, distilled, skewed and subtly changed, in the way in which a

day’s events can take on new and unexpected significance when they

reoccur later in our dreams.  When

the grid-like, geometric substructure that is visible in a number of

Annear’s recent paintings is pointed out, he cites the example of

Aboriginal art, in which the practitioners sometimes enter a trance-like

state in which they believe they see the earth from above. He also

mentions the inspiration of the bleak and mysterious Teufelsmoor in

Germany—the landscape in which he painted during his residency at

Worpswede. During this period he had, at first, the greatest difficulty

engaging with the flatness of that landscape, made up of seemingly

endless featureless acres of bog and marsh reclaimed from the sea. In

time he came to view the network of dykes, black peat banks, ochre-green

land and the dazzling silver-blue cobalt of the water lying in the

drainage channels as forming a linear scaffold across the landscape, the

marks of a wonderful conjunction of the natural with the man-made. This

network of straight lines and curves—taking over from and giving way to

one another—recur in more recent treatments of his native landscape. It

is reminiscent of the way in which the train line that conveys one the

six and a half hour journey from Paddington carves its way across great

tracts of England, forming eccentric and pleasing angles with the many

miles of hedges, walls and drainage ditches en route. Though these

ancient scars and barriers, built on or carved out of the body of the

landscape seek to impose order, they often deviate from the strictly

rectilinear and are softened by the elements, making way for one

another, or for a great river, or an untidy copse of trees of greater

antiquity than themselves.

When

the grid-like, geometric substructure that is visible in a number of

Annear’s recent paintings is pointed out, he cites the example of

Aboriginal art, in which the practitioners sometimes enter a trance-like

state in which they believe they see the earth from above. He also

mentions the inspiration of the bleak and mysterious Teufelsmoor in

Germany—the landscape in which he painted during his residency at

Worpswede. During this period he had, at first, the greatest difficulty

engaging with the flatness of that landscape, made up of seemingly

endless featureless acres of bog and marsh reclaimed from the sea. In

time he came to view the network of dykes, black peat banks, ochre-green

land and the dazzling silver-blue cobalt of the water lying in the

drainage channels as forming a linear scaffold across the landscape, the

marks of a wonderful conjunction of the natural with the man-made. This

network of straight lines and curves—taking over from and giving way to

one another—recur in more recent treatments of his native landscape. It

is reminiscent of the way in which the train line that conveys one the

six and a half hour journey from Paddington carves its way across great

tracts of England, forming eccentric and pleasing angles with the many

miles of hedges, walls and drainage ditches en route. Though these

ancient scars and barriers, built on or carved out of the body of the

landscape seek to impose order, they often deviate from the strictly

rectilinear and are softened by the elements, making way for one

another, or for a great river, or an untidy copse of trees of greater

antiquity than themselves.