|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Adam Scovell on Folk Horror, TV and the landscape e-interview by Rupert White

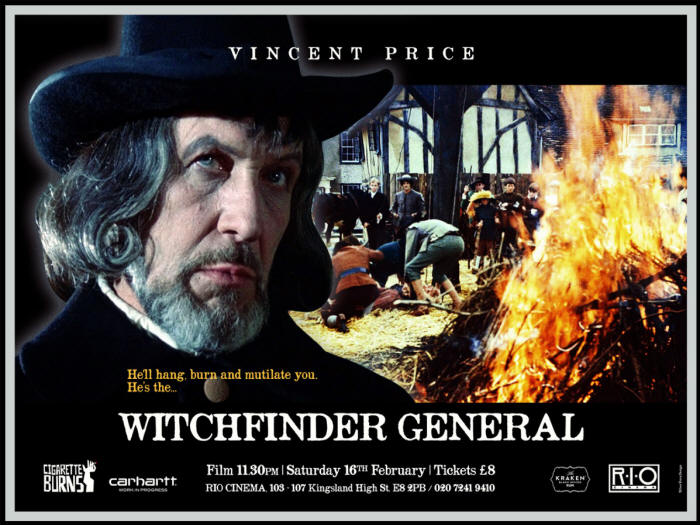

Who first coined the term 'Folk Horror' and to which films were they referring? In its current use, the term was first coined by Piers Haggard when describing his film The Blood On Satan's Claw (1971). Recently, there's been a whole host of new searching for earlier examples of the term, largely through online academic portfolios and many older uses of it have come to light, even as far back as the 1930s. However, these are mostly unqualified uses and, though interesting, are largely sought so people can find the oldest use and attribute it. Haggard's, however, is the benchmark as it is actually talking about work of relevance. Mark Gatiss then took the term (actually from that interview) and popularised it in his documentary series A History Of Horror in 2010 which is really when the genre comes into its own and people start talking about it in the context of Robin Hardy's The Wicker Man (1973) and Michael Reeves' Witchfinder General (1968) too.

In your book you describe these three key films as being linked by a 'Folk Horror chain'. Can you explain what this is? The chain is just one idea that was brought about to connect that trilogy of films. Each one is incredibly different from the other so forming a genre around them at first seems illogical and open to criticism. But the chain is one way to counter this by building on the rural landscapes of the films which then isolate the characters, skew their morals and allow violence and more supernatural happenings to occur. There are other connections between them, especially aesthetically, but the chain ties them together as neatly as I think is possible.

These three films were all made in the period between 1968-1973, which were key years for the counter-culture in this country. What relationship do they have to the counter-culture, would you say? They definitely channel some aspects of the counter-culture, especially Blood which taps into its dark endpoint of Charles Manson et al. But I actually think the trilogy feel the wrong way round in terms of the counter-culture they're tapping into. Witchfinder is a kick in the teeth to the optimistic side of the counter-culture in 1968 whilst The Wicker Man (picture below) is incredibly optimistic for a British film made in 1973 when the country was basically on its knees, and the hippy dream had died a violent death. So they can be seen to comment on the counter-culture but not in a straightforward way.

What about their relationship with Hammer Horror: films which were often much more stagey and theatrical? Were they responding to a need in audiences to see something that was filmed in settings that were more real, perhaps? I think Witchfinder is definitely a response to some of Hammer's pomp but Hammer had a very dark strain running through their films from the off. Of course, by 1968, their Gothic pomp had dominated and rightly so because it was brilliant. But they also had many other films outside of the period Gothic which worked incredibly well, even touching on Folk Horror. Quatermass and the Pit and The Witches are the obvious examples, alongside their underrated strain of psychological horror and even the strangeness of The Damned, The Nanny and The Crimson Blade. John Gilling's double bill of The Reptile (pictured below) and Plague of the Zombies even moves the drama to Cornwall (though they're filmed in the usual Slough back-lot). So Hammer's output is far more varied than people often consider.

What do you think Folk Horror tells us about our relationship to folklore and the landscape? At some level these films all seem to offer a critique of urbanisation and modernity don't they? It's a complicated relationship and it really depends on which film we're talking about but generally I think Folk Horror is quite refreshing in its sense of anti-nostalgia about the questioning of social violence and the British psyche especially surrounding the landscape which has for a long time been a very Conservative zone. It is also somewhat questioning of modernity though I wouldn't link it so much to urban landscapes though some films do make that link (Requiem For A Village for example). But yes, modernity seems to be the enemy in Folk Horror with its dismissal of the "old ways" and which ties heavily to current British politics at least as modernity does represent a global openness which is increasingly dismissed and at risk.

Does this help explain why these works have been rediscovered by a generation, like yourself, who were born several years after they were made? What do you think is the basis of their appeal now? In fairness, the new revival of Folk Horror is generally maintained by the generation above me who grew up in the 70's and 80's and I think my generation of millennials have cottoned on to it as there's clearly a huge gap in the experimentation and daring in television in particular that Folk Horror was clearly a part of. I'm a bit of a baby in the group by comparison, but I definitely feel when watching some of the old Play for Today episodes - for example, Robin Redbreast, Penda's Fen, Red Shift - that something has been lost in terms of popular narrative and the willingness to experiment and challenge in solely creative ways. You could call it a false nostalgia but then, if I find myself stuck with something from the supposed new golden age of television (which is basically American and gives you everything on a plate at every opportunity), I can't help but crave for something with a patience to it. Something like Robin Redbreast or even a children's program like The Owl Service makes most new programs seem rushed and simple.

Can you recommend any contemporary directors that are tapping into the essence of Folk Horror? The obvious name to mention is Ben Wheatley but there are plenty of others. Paul Wright, Robert Eggers and others are all tapping into its essence though I actually think there's a sense of it being adapted into modern literature and music too. The most effective evocation to me is in the musicians on the Ghost Box record label who are clearly fluent in the past material but using it to create something new and interesting.

Adam Scovell is a writer https://celluloidwickerman.com and author of 'Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange' 25/9/17

|

|

|