|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Alan Kent

on the literature and theatre of Cornwall

Alan M. Kent is a Cornish poet,

You

studied English at University. When

did you start

writing yourself? I studied English Lit at the University of

Wales, Cardiff The earliest pieces were more surreal I suppose. There was no cultural nationalist view. That emerged as I developed.

'Clay' was a bildungsroman - almost autobiographical in a way. As was 'Proper Job: Charlie Curnow!' because it was about an alternate me - set in Camborne rather than the clay landscape I grew up in. But in the Trelawny Trilogy there are lots of comparisons and similarities. 'Voog's Ocean' sold badly in my view - that's because it was a magical realist text - people didn't know what to make of it. And it was so different from what the earlier novels had established me as. 'Voog's Ocean' is now appreciated more than when it came out. People who have read it love it. 'Dan Daddow' is a new direction but a novel that I had wanted to write for a very long time. In it I push the limits of history but I wanted to do that. It was also interesting to write about a bisexual character which might alienate some people, but it's as much a part of Cornish history, as any other culture's history. When did you first learn to read and speak the Cornish language? Did that change your own writing? The moment I lived in Wales I understood that I had to know more about Cornish culture and language. The big change came though around 16 when in a flea market in Truro I picked up Peter Berresford Ellis's 1974 book 'The Cornish Language and its Literature'. It was a 'Jedi' moment. There was all this culture that I should know about but had never been taught about at school. I felt cheated. I needed to know more. Another early influence was Denis Trevanion who taught me Cornish in the sixth form as part of the general studies programme. A great chap. When at University there was an Australian medievalist called Roger Ellis who spoke to me a lot about the Cornish plays - he was very interested in them. He was another inspiring figure.

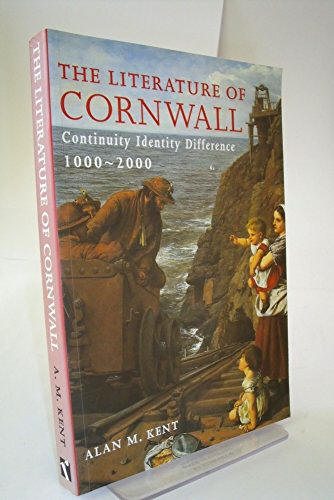

Yes. It was an important book in synthesising an overall history of English, Cornish and Cornu-English writing about Cornwall. I would do it completely differently now, but it is a marker so to speak.It came about by me initially talking to Charles Thomas about completing a Ph.D at the Institute of Cornish Studies on it, but by the time it all happened, it was Philip Payton who was running the Institute. At that time, in order to work in this field it needed to be completed jointly with a department at Exeter. Naturally that was the English department and my supervisor there was Peter Faulker - an expert in critical theory and post-empire studies. He had previously supervised my M.Phil in Cultural Materialism. I had brought a lot of good critical knowledge from Cardiff where I had learnt from Terry Hawkes, Christopher Norris and Catherine Belsey. How did you decide what to include? It had to be anything that offered a construct ion of Cornwall in either Cornish, English or Cornu-English. Birthplace of the author doesn't really come into it. I wanted to cover everything from year dot to the present.Can you explain the se categories a bit more? What is Cornu-English for example?I hate the term dialect which a lot of people seem to use. English has several dialects. We ought to say Cornu-English which is more correct. Thankfully academia seems to be using that term now.I suppose this might include any writing in Cornu-English but within it there are huge differences. e.g. the kind of thing I wrote in Proper Job, Charlie Curnow! is very different than the dialect in aspic: tying the donkey up the post/on the Carn-style stories. Anglo-Cornish can be all kind of literature from all kinds of writers - but principally it is literature written in England about Cornwall or Cornish experience. Cornish literature is the odd one in the sense that some Cornish literature can be on non-Cornish subject but can be just as culturally valid. Indeed the revival of Cornish focused on resolutely Cornish material but maybe that was a mistake?

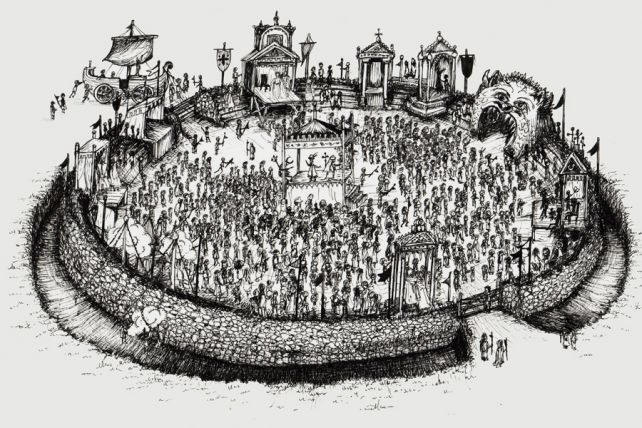

There is some overlap of this book with another of your major studies 'The Theatre of Cornwall', particularly in discussion of the medieval Ordinalia (picture above by Heidi Ball). Can you say something about the Ordinalia?I have always described it as like a dramatic Bib lical Star Wars! There are three extant interconnected plays all written in the Cornish language (Middle Cornish).The core connection is the holy rood - the wood that makes the cross of Christ's crucifixion. For me Ordinalia ought to one of Cornwall's biggest contribution to European culture and tourism. If marketed in the right way it would draw thousands of people here but also ought to be toured around the world. What is the relationship of your own plays to the rest of your writing? Integral. Plays offer a debate on stage. They are less preachy than poetry. I like characters debating things. Most of the characters are based on people I know - or components of them. They tend to come out in historical visions of Cornwall - I am not sure why. However, I still think they make contemporary comment. Talking of historical visions, I was lucky enough to witness 'The Life of St Piran' on the sand-dunes of Perranporth earlier this year. How did you get involved with this? I was commissioned by the St Piran Trust to write a new St Piran play in 2013. It seems to be a rite of passage for Cornish dramatists, and I think that's a good thing. The thing I fundamentally had in mind, is that in the medieval period there would have been a real 'Life of St Piran' performed a 100 metres away at Perran Round. I tried to take some new plot lines with the text - involving King Arthur, and extending the mining sequences. I also wanted the coracle to evolve into a surfboard. Maybe that will happen one time! The title 'Bewnans Peran' was a direct nod to the epic drama of the past. Of course when you are writing this kind of stuff - every line is epic and grand (Lord of the Rings style rather than Harold Pinter) which is different to my other work but similar, I suppose, to the translation of Ordinalia - so it does come back full circle. In the early evolution of the project I met with the Trust and we talked a lot about the site-specific possibilities. It has been made a bit more complicated these days by the uncovering of the oratory and the expansion and deepening of the lake.

Would you say you're also open to less 'authentic' constructions of Cornwall? I could imagine some purists might have a problem with your most recent production, for example.The thought of me (as nationalist writer in essence) adapting 'The Mousehole Cat' is an an interesting one. The story has been labelled inauthentic and Anglo-centric. Critics have also argued that it neglects the Methodist origins of the narrative, and that such work increases desire for second homes in such places as Mousehole. I see that.However, fundamentally the story of Tom Bawcock is one of our mythic narratives. We own it. It is us. Therefore I think it important that someone like me has a go at adapting such a work. It is an interesting fusion so to speak. What I hope is that whatever "baggage" the story has, has been removed in the production - and its Cornishness is enhanced. Visually the children's book is stunning. I don't think anyone could argue against that. Hopefully the theatre production does this justice. Also, it is important for me to try this kind of work. I can't continually bang the drum. My last play 'National Minority' was the ultimate statement of that dramatic nationalist aesthetic. I won't repeat it. To an extent too, I think it important that the public see that as well as writing things like National Minority I can also adapt something more gentle and dream-like. In the end, both have the same aim to culturally put Cornwall on the map - to show what we can do and what a range of stories we have to tell.

It has widened and got better in some ways. In the 1990's doing Cornish Studies was still seen as weird or strange. At the same time, the Institute of Cornish Studies has been sidelined by the University of Exeter, and at best, still tries to carry forward that energy. But it needs more staff, more research, more acceptance. I don't really see Exeter supporting Cornish Studies. In fact, we have an imperial university riding over what should be our own institution. Falmouth University is no better. It is clueless about real Cornish Studies. How do you see the future of Cornish culture? Isn't it inevitable that Cornish identity will be slowly eroded through processes of globalisation? No. I think it is more resistant and harder-fought for than ever. People are now more confident about their identity and sense of place. I see it growing, as a positive reaction to globalisation. The Cornish are becoming better at articulating their past, their present and their future. 28/12/16

for a full list of Alan Kent's published works see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_M._Kent |

|

|

How

would you describe your early published novels, in terms of their

setting and genre?

How

would you describe your early published novels, in terms of their

setting and genre?  Your

book 'The Literature of Cornwall' (2000)

Your

book 'The Literature of Cornwall' (2000)