|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Dominic Shepherd on Black Mirror, art and the occult Interview Rupert White

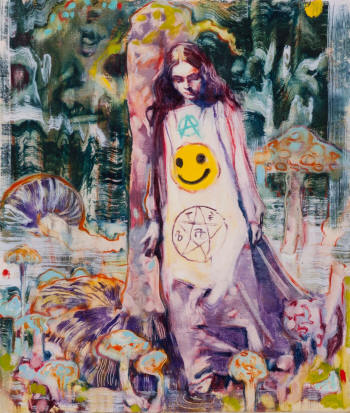

Judith Noble and I met at the Arts University Bournemouth in 2013. We established fairly quickly our mutual interest in the occult and magic. Judith saw my artworks in an exhibition in London (eg 'Baptism' (2012) right), and she was organising 'Visions of Enchantment' conference at Cambridge University with Dan Zamani. Through discussion we realised there was a space and need to create a platform that explored the influence of the occult, magic and enchantment on modern and contemporary visual arts. We formulated, with the help of Arts University Bournemouth, the premise for the Black Mirror research network. Very quickly Robert Ansell of Fulgur Esoterica joined us in wishing to publish a series of volumes to further our aims, which was fantastic. Through Robert we met Jesse Bransford (cf picture below left) of New York University and so it has grown into an international network. Still it grows.

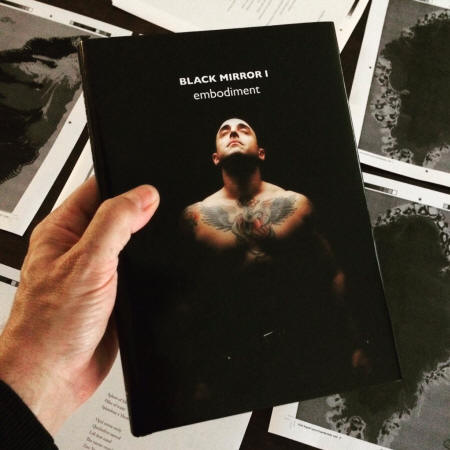

What is the thinking behind each publication, and what kind of spin-off projects have there been? The Black Mirror publications are seen as a forum for serious engagement with the aims of Black Mirror. The series of volumes is mapped on the Sefirot (tree of life), mirroring it to themes that engage with contemporary artistic issues. Recent titles include 'Embodiment', 'Elsewhere' and next 'Patterns'. Each edition’s contributions are selected through a peer review process, and we are pleased to be receiving abstracts from across the globe. In each edition we also include a selected artist’s portfolio. Large projects have included the 'Visions of Enchantment' conference where we launched Black Mirror, but also smaller art events such as 'Absolute Elsewhere' that was an evening of occult music and art set in Shelley Manor commissioned by Bournemouth Arts Festival. The network members have also been spreading the message at conferences and as invited speakers. Recently Judith for 'Alchemical Landscapes' at Cambridge, and Jesse and I at Volta, New York. Next March (22-23rd) Judith Noble has organised ‘Seeking the Marvellous’, a conference exploring the legacy of Ithell Colquhoun, that is being hosted by Plymouth College of Art where she is now Associate Dean. It promises to be an opportunity to further reassess the legacy of this major, yet marginalised, artist.

I saw it at the Towner Art Gallery in Eastbourne. Yes, it was a seismic shift in the discussion around the occult and art. Previous hegemonies of thought consistently marginalised the magical in 20th century visual arts, seeing it as a ‘process’ used to create, rather than an intrinsic driver. ‘The Dark Monarch’ was a game-changer that placed the magical centre stage, leading to an increasing acknowledgement of the occult within the artistic and academic community. I remember very well, as do many others, that in the 1980/90's mention of the occult would be met with the ‘cranky’ moniker.

What other factors have helped with this acknowledgement? Have particular books been important? Suzi Gablik's 'The Re-enchantment of Art' (1991), perhaps?In the introduction to Black Mirror 0: Territories 'The Re-enchantment of Art' is stated as a seminal text. For many bewildered artists in the late 1980/90's it was a revelatory book that did exactly what it says on the label: held up enchantment in an age of irony. But where Gablik really added relevance was her alignment of the magical with progressive values. Alex Owen’s 'The Place of Enchantment' (2004) continues this view, exploring the parallels apparent in early modernism and the nascent occult scene in the late 19th Century. I believe the greatest factors in the process of acceptance have been external to academic or artistic thought and that is the changing world. Magic and the occult have been increasingly relevant and used in the debates raging around political, environmental and social movements. From pagan environmentalism to the witch as proto-feminist, the use of the magical is a form of giving power to those who are powerless. Artists occupy a similar powerless zone and have rapidly responded, acknowledging that power. Added to this is the digital world, an immersive environment of predictive algorithms, world creation and charismatic memes and we have a potent brew.

A couple of years ago I was very lucky to see ‘Artists and prophets a secret history of modern art 1872-1972’ at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt. It shone light on the parallels between the febrile political landscape within Germany and the visionary artists and wandering prophets who reflected that state, from Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach to Jorge Immendorf. The thirst for visionary ideal and occult art as a shaper of the zeitgeist, to both the right and the left, is pertinent.

What kind of angle will you, as curator, be taking for the forthcoming exhibition at Arts University Bournemouth? I think all the artists are 'contemporary', rather than historical. Is that true? Many of the artists have featured in the Black Mirror publications. The artists are contemporary in that all the work has been created in the last 30 years. The approach to the exhibition is to show how these artists, who work within the magical and occult, look outwards and use powers to question or effect current social, political and philosophical viewpoints. And to see the exhibition space as oracular.

Do they represent different esoteric traditions (eg Western European) or different ideas of the occult?

How many of the other participants could be described as practising occultists, and does that even matter? Some of them are, but artists can be very private. Creativity is a magical act; the imaginative will becoming real. The drivers of creativity are parallel with those of the magical. Interestingly one of the exhibited artists, dark pastoralist and creator of fairies, Tessa Farmer, was initially reticent about acknowledging the occult in her work. Acknowledgement came when it was revealed to her that her great-grandfather was Arthur Machen, the master of dark pastoral.

'Black Mirror: Magic in Art' opens at AUB on 23/11/17 and continues to 1/2/2018. Dominic Shepherd is a practising artist and Associate Professor at Arts University Bournemouth. |

|

|

Talking

of which, did you see 'The Dark Monarch' (2009) at Tate St Ives? To me

it seem

Talking

of which, did you see 'The Dark Monarch' (2009) at Tate St Ives? To me

it seem Have

you been impressed by other shows that have had a strong occult/magical

influence?

Have

you been impressed by other shows that have had a strong occult/magical

influence? The

artists all hail from North America and Europe, so I suppose one would

describe it as the Western tradition, although some juggling can be

seen. Jason Martin’s rock 'n' roll she-wolf power-animal persona bows

towards native Americanism, and Jesse Bransford’s wall-piece looks East.

I am very pleased that as part of the exhibition programme on January

18th we have a practitioner of palo mayombe, William Hernandez, who has

devised a Cuban dance rite. This will be followed by a talk on ritual

dance by Naomi Watts of the sacred trust.

The

artists all hail from North America and Europe, so I suppose one would

describe it as the Western tradition, although some juggling can be

seen. Jason Martin’s rock 'n' roll she-wolf power-animal persona bows

towards native Americanism, and Jesse Bransford’s wall-piece looks East.

I am very pleased that as part of the exhibition programme on January

18th we have a practitioner of palo mayombe, William Hernandez, who has

devised a Cuban dance rite. This will be followed by a talk on ritual

dance by Naomi Watts of the sacred trust.