|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Richard Gendall on Brenda Wootton, Morton-Nance and the Cornish language The late Richard Gendall wrote songs for Brenda Wootton, and as an expert on the Cornish language held a chair at Exeter University. Interviewed by Rupert White in 2012.

Can we start by talking about folk music from Cornwall?

There is n't much Cornish language folk music. There is one song with music and words and that's slightly doubtful. 'Pela Era Why Moaz, Moes Fettow', which is a Cornish version of 'Where are you going to my pretty maid', is the only one. There is a tune that goes to it but no-one is sure if its the right one or not. It's very sketchy. There is a certain amount of English language Cornish folk music. Even then there is not a vast quantity and all the genuine stuff is in collections published by Baring-Gould and Ralph Dunstan. There is the odd one or two in Cecil Sharp house. I picked up one or two there that hadn't appeared anywhere else.

Baring-Gould published his 'Songs of The West'. The songs of Devon

and Cornwall tend to cross the boundaries. A lot of the better ones

are from Devon, a lot of the Cornish ones are the jolly 'pubs are

shut' type of thing. Many were collected in West Cornwall.

How did an interest in folk song lead to your collaboration with Brenda Wootton? (above on stage at Kerltag) I was a teacher. In 1960 I went to New Zealand, up to that time

I'd been teaching in Helston, then I came back and taught in Helston

again, and stayed there until I retired. Most of my teaching was in

Helston Grammar School.

In 1972 Brenda Wootton was asked to represent Cornwall at the

Killarney Pan Celtic Festival in Ireland. She had to sing a song in

the Cornish language, so the organisers in Cornwall sent her to me.

There weren't any songs in the Cornish language then. She had to

have a genuine folk song, so I supplied her with Tryphena Trenerry,

and with one of my own which passes as folk music. There is no

genuine Cornish language folk music really. So she sang Tryphena

Trenerry in English, and my one in Cornish, and that's when she

started singing Cornish folk music.

She didn't really know what was Cornish, and what wasn't. So I sent her stuff from Baring-Gould and other sources, for example 'Soldier on the Battlefield' and 'Jan Knuckey'. I gave her lots of stuff that she hadn't heard of. We used to spend evenings going through them, at Leskinnick and at her place in Penzance near the harbour, and she used to come to my place near Camborne, and we would spend hours together with a guitarist going through them, learning them by rote. She prided herself on not being a trained musician. She tended to make mistakes, to misinterpret things and mislearn things. Once she'd learnt a mistake it was hopeless and hard to get it right again! But she was a really great performer and she took masses of my stuff. Eventually she was interested in seeing the music that I composed, and I started writing music for her on a range of themes that she was interested in. Her interest spurred me on, so I wrote more and more and more. As long as she was able to take them I was able to compose them! She went to the continent, and was well received and eventually felt strong enough to go professional.

Did you ever play live with her, or record yourself? I didn't play music that seriously. I played guitar for my own accompaniment. She and Job Morris produced a record called 'Children Singing' and I played guitar on that and on 'Crowdy Crawn' but I don't pride myself on being a super guitarist. I can play enough for my own satisfaction and sing to people. but I'm not really a public performer, and never played in the clubs.

You can't write genuine folk music. Because it's developed over a

number of years you can take it and learn it and adapt it or

whatever. My own music is based on themes that are common to the

whole of Britain. I was strongly influenced by Welsh and Irish and

Scottish music. You are influenced by what you hear. During the war

when I was stationed in Clydemouth and I had an old radio, I picked

up old Irish songs. Everyone tends to write based on what they've

heard before.

Do you consider a song like 'Trelawney' folk music? Trelawney was written by Rev Steven Hawker but it was souped up a bit. The tune is not Cornish at all. It's a tune that has been adapted and turned into a Cornish song but in fact it's a Yorkshire song, I think. Most songs cross borders and become popularised. Camborne Hill I'd call a 'pubs are shut song'. You sing it when you come out of the pub roaring it at the top of your voice! A folk song is a song that doesn't have a composer. In the old days nobody bothered to put their name to a song they just sang it in the pub, and somebody said 'I like that' and they sang it and maybe added a bit to it and it got passed on. Did you manage to teach Brenda Wootton some Cornish?

Brenda wasn't very good at Cornish. She was

very interested in it but she wasn't

really ready to learn it

properly. She would learn it parrot-fashion,

but never told anyone that she didn't really understand

it herself. But she was such a good performer and she'd

stand up on the stage and bold as brass she'd sing

anything. She presented

herself so well, with everyone

hanging on her every word,

no-one challenged her, or

thought to ask her where things came from.

How did you yourself learn Cornish?In 1938 Robert Morton Nance did a Cornish into English dictionary. It's not a bad dictionary. Then he did an English into Cornish which came out in 1952 which I prepared for him. I took his 1938 dictionary and reversed it for him, turned it inside out and handed it back to him. He was living at Carbis Bay. I was born in 1924. I was a student at Leeds Uni, and I was studying language, and in my teens had been given a copy of his dictionary by my parents as a Christmas present. I was longing to find out all I could about Cornish. When I came back form the war and went to University I got into touch with him, and we had a loose friendship and exchanged letters and so on. And I got more and more into the language that went on from the war years right on to recent times.

There is more interest in Cornish now than there used to be,

but it's got side-tracked

and gone off on the wrong track. The group of people who are

trying to do most about it now

know least about it. What is coming out of the production

line is a helluva lot of rubbish. I stick to the language as

it finished up before it died out,

which is as it was in the 1700s. The language was

effectively dead by about 1710. Nobody was actually talking

Cornish on the streets anymore. As a community language it

had gone.

What are the main sources of modern Cornish?

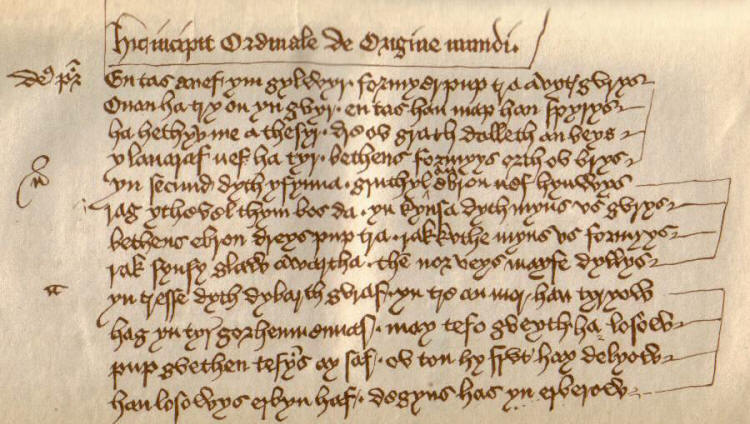

If you go back to the Middle

Ages you've got the religious

dramas mostly written in the 1400's

(photo above Origo Mundi, the first play of

the Ordinalia). Then

in the 1500's you've got the

miracle plays coming out, and a

long series of sermons turned into Cornish by John Tregear.

Then in the 1600's the language

takes a big turn, because

in the Middle Ages

the only people that could write in the language were

parsons, and monks,

and clerics. All Cornish up to

about 1600 was based on religious drama. And you can't

really base a revival of a language on religious drama. You

can get a lot out of it, but an

awful lot is missing.

When you get to 1660 there are one or two writers who have nothing at all to do with the church and they were writing the language as they knew it, and it looks completely different. That's where modern Cornish comes in. When you get to 1700 the principle writer was called John Boson - go to Truro museum you'll find a leaflet on the Cornish writing of John Boson - that's how the language looked when it was used by ordinary people. Boson wanted to save the language, and by the time he was involved it was beginning to fail badly. He realised that one of the weaknesses was its spelling system. In the first few years of the 1700's the language was rewritten with a new spelling system. I don't know if you are familiar with the map of Penwith, but there is a place west of Penzance called Caer Brân, which is a name which has a circumflex. Accents were one of the principle features of modern Cornish because it meant you didn't have to jam together different letters. All the accents used in modern Cornish can be found somewhere on the map, like Chûn Castle, and Mên an Tol. They got on the earliest maps probably through the Reverend Borlase.

Morton Nance was as funny old guy - he was like a little old

woman! He didn't use accents.

He wanted to take the language back as far as it

would go without it breaking. He

went right back into the Middle

Ages and tried to write a

Medieval Cornish

which he pretended was modern, but

it didn't really work. Morton

Nance's is 15th century Cornish

without the modernisations. It was Medieval

Cornish parading as modern...

Richard Gendall died aged 92 in 2017. See tribute https://www.brendawootton.org/richard-gendall Also see Folk in Cornwall https://www.amazon.co.uk/Folk-Cornwall-Musicians-Sixties-Revival/dp/0993216404 10.5.19 |

|

|