|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Rose Hilton Alex Wade

“I know you’ve been painting because I can smell the turps.” Thus spoke Roger Hilton, one of the pioneers of British abstract art, to his wife Rose. The scene for this declaration was the couple’s home in Botallack, a remote village in the far west of Cornwall; its timing a few years into their oft-tumultuous, but enduring, marriage. If Roger Hilton’s words suggest less by way of cosy domesticity and more that a line had been crossed, that is precisely what had happened.

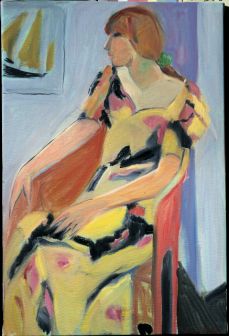

Roger Hilton died in 1975, aged 63. Already widely known at the time of his death – in some quarters, as much for his acerbic tongue as his painting - his stature has since grown so that he is recognised, along with Sir Terry Frost and Patrick Heron, as among the key figures in post-1950s British art. Last year saw the publication of art critic Andrew Lambirth’s book Roger Hilton: The Figured Language of Thought, yet further consolidating his reputation. But as her first solo retrospective at the Tate St Ives shows, Rose Hilton is as deserving of recognition as her late husband. This is a painter whose understanding of colour and tone is exceptional, whose canvasses are soft, beguiling, nuanced and diffuse, and whose sense of fidelity to her work is, ultimately, every bit as uncompromising as Roger’s. Rose Hilton, nee Phipps, was born in Kent, in 1931, into a devout Plymouth Brethren family. She showed great promise at the Royal College of Art in London, winning the Life Drawing and Painting prize as well as the Abbey Miner Scholarship to Rome. Upon her return to London, she began teaching art, and, aged 28, her life “was all mapped out. I was painting and showing my work, I had a nice flat in Chelsea. Then I met Roger.” The pair met through another luminary of British abstract art, Sandra Blow, who described the wartime Commando as “Trouble”. Despite this, by summer 1959 Rose had sought out Roger in his Newlyn studio. “He was incredibly charming and fascinating,” she says. Moreover, as she told Lambirth, “I put it down to my background in the Plymouth Brethren, being taught to love Jesus. Roger was my Jesus of the art world.” If

Roger Hilton had Christ-like qualities, they did not extend to

tolerance, still less encouragement, of his The Hiltons, with their sons Bo and Fergus, decamped from London to Cornwall in 1965. By then they were married, and despite his penchant for disruption Roger’s star was on the ascendant. It survived his appearing to aim a kick at March 1963, his painting that won the prestigious first prize at the John Moores Exhibition in Liverpool, and even emerged unscathed after the death of Alderman John Braddock, a guest at the Exhibition’s awards ceremony who, offended by something Roger said, died of a heart attack. Rose is typically candid: “He could be terribly rude and provocative. But he was never violent, even when he was drinking.” In Cornwall, drinking became somewhat more than a pastime for Roger Hilton. Repeated attempts to dry out, at the Priory and elsewhere, failed, though Rose notes wryly that her husband postponed one relapse long enough to attend Buckingham Palace, sober, to collect his CBE. Curiously, Roger’s drinking enabled Rose’s own modest transgression, for when he was drinking, she could – covertly – paint. “Roger would often go off drinking with Sydney [Graham, the poet]. When he was gone, and with the boys at school, I would paint.” Just prior to Roger taking to his bed for his last years, she was discovered. “He smelled the turps and asked me to show him what I’d been doing – a still life. It was a very exciting, but fearful, moment for me.” Roger’s verdict? “He said ‘If you must do this old-fashioned painting, I can help you do it better.’ I learnt more from him in an hour than I did in the whole of art school.”

But Rose is not the kind to boast. She lets her paintings do the talking and lives quietly in Botallack, in the same cottage to which the couple moved in the 1960s. Although she and Roger had separate beds by the end of their marriage, Rose has now moved into the room that served as Roger’s studio and his living quarters for his last three, bedridden years. Outside the ancient granite cottage, the Atlantic pounds the cliffs and the abandoned tin mines are visible, and along the coast at St Ives, preparations are underway for Rose’s show at the Tate. It is tempting to see her work – at once subtle and intimate, elegant and controlled, each painting irreducibly feminine – in opposition to the masculine hardness, of gaze and line, in Roger’s canvasses, but such musings are interrupted by A Heart So White, Javier Marias’ novel of the multiple ties that bind – and unravel – in love and marriage. The book sits on a bedside table - “Marias is a wonderful writer,” says Rose, “his sentences are exquisite.” Its ending, when the narrator speaks of the “murmured feminine song” of his wife, leaps from the page: “A song that is sung despite everything, but that is neither silenced nor diluted once it’s sung, when it’s followed by the silence of adult, or perhaps I should say masculine life.”

Rose Hilton: A Selected Retrospective shows at The Tate St Ives, 26 January – 11 May 2008. Drawings by Rose Hilton will also show at the HiltonYoung Gallery, Chapel Street, Penzance 26 January – 6 March. |

|

|

Rose

had infringed one of the fundamental tenets of their relationship: “We’d

been together for a little while and one day Roger said to me, ‘It’s

working, you and I, but I’m the painter in this set-up – and don’t

forget it.’ That was the way it was. He was the artist. I was the wife

and mother.”

Rose

had infringed one of the fundamental tenets of their relationship: “We’d

been together for a little while and one day Roger said to me, ‘It’s

working, you and I, but I’m the painter in this set-up – and don’t

forget it.’ That was the way it was. He was the artist. I was the wife

and mother.”  wife’s own artistic needs.

His prohibition on her painting will strike contemporary ears as the

most remarkable chauvinism, but perhaps as surprising is that Rose

accepted it without demur. Tall, slender and still, at 75, languorous

and feline, she appears self-possessed and certain, not the kind of

woman to kowtow to a man. But hindsight provides perspective. “I believe

in feminism but came from a generation that missed out on it,” she says.

“Perhaps I could have made a wiser decision in dealing with him, but I

was very much in love with Roger. He had tremendous integrity as an

artist, which was something I needed in my life. I also had my children,

and so was fulfilled in another way.”

wife’s own artistic needs.

His prohibition on her painting will strike contemporary ears as the

most remarkable chauvinism, but perhaps as surprising is that Rose

accepted it without demur. Tall, slender and still, at 75, languorous

and feline, she appears self-possessed and certain, not the kind of

woman to kowtow to a man. But hindsight provides perspective. “I believe

in feminism but came from a generation that missed out on it,” she says.

“Perhaps I could have made a wiser decision in dealing with him, but I

was very much in love with Roger. He had tremendous integrity as an

artist, which was something I needed in my life. I also had my children,

and so was fulfilled in another way.”  Rose

grieved terribly for Roger: “I was very overwrought. It took a while for

me to get unbent.” But immersion in her work – so long deferred – was

inevitable and essential. In 1977, she had her first solo show at Newlyn

Art Gallery, and 25 years later she could list numerous exhibitions

around the country and especially at Messum’s, in Cork Street. If she

were the kind to boast, Rose Hilton could lay claim to a body of work

which, in its post-Impressionist, figurative roots allied with an

increasing tendency to abstraction, is as vibrant and compelling as her

husband’s opus. Bonnard and Matisse are obvious influences, but she has

created an artistic language so much her own that it is easy to agree

with Lambirth who, introducing a 2004 show at Messum’s, wrote “[her]

pictures proclaim a single author. In their freshness and lyricism, in

the assured design and inventive palette, above all in their

edgily-balanced description and decorativeness, these pictures could

only be by Rose Hilton.”

Rose

grieved terribly for Roger: “I was very overwrought. It took a while for

me to get unbent.” But immersion in her work – so long deferred – was

inevitable and essential. In 1977, she had her first solo show at Newlyn

Art Gallery, and 25 years later she could list numerous exhibitions

around the country and especially at Messum’s, in Cork Street. If she

were the kind to boast, Rose Hilton could lay claim to a body of work

which, in its post-Impressionist, figurative roots allied with an

increasing tendency to abstraction, is as vibrant and compelling as her

husband’s opus. Bonnard and Matisse are obvious influences, but she has

created an artistic language so much her own that it is easy to agree

with Lambirth who, introducing a 2004 show at Messum’s, wrote “[her]

pictures proclaim a single author. In their freshness and lyricism, in

the assured design and inventive palette, above all in their

edgily-balanced description and decorativeness, these pictures could

only be by Rose Hilton.”