|

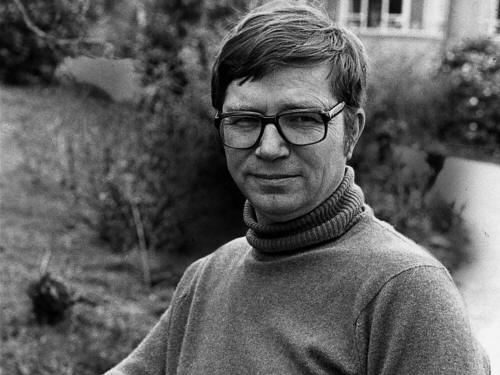

Colin Wilson: Strength to

Dream Marcus Williamson

Colin Wilson was one of the most prolific and

eclectic writers of the 20th century. In more than 150 books and

countless articles and contributions to other works, published over 50

years, he covered subjects as diverse as existentialism, esotericism and

the occult, religion, biography and several volumes of autobiography. It

is his groundbreaking work on existentialism and creative thinking,

The Outsider, published to wide critical acclaim in 1956, that

remains his best known work.

Wilson

was born in Leicester in 1931, the son of a shoemaker. He left school

aged 16 and over the next eight years took on a variety of unskilled

jobs while writing. “I kept a voluminous journal, which was several

million words long by the time I was 24,” he recalled. Since the age of

12 he had been preoccupied with asking the meaning of human existence

and at 14 had read George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman, from which he

realised that “I was not the first human being to ask the question.” Wilson

was born in Leicester in 1931, the son of a shoemaker. He left school

aged 16 and over the next eight years took on a variety of unskilled

jobs while writing. “I kept a voluminous journal, which was several

million words long by the time I was 24,” he recalled. Since the age of

12 he had been preoccupied with asking the meaning of human existence

and at 14 had read George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman, from which he

realised that “I was not the first human being to ask the question.”

Living rough on Hampstead Heath, working at a café and spending his days

at the Reading Room of the British Museum, he had been trying to write a

novel when the outline of The Outsider came to him. Photographs from the

time show the handsome bohemian figure sitting alone, leant against a

tree, wrapped in a sleeping bag and with a book in hand.

Inspired by the title and content of Camus’ novel l’Etranger (The

Outsider, 1942), he sought to rationalise the psychological dislocation

associated with Western creative thinking. Wilson took the outline and

sample pages to the publisher Victor Gollancz, who immediately accepted

the book. Published on 26 May 1956, The Outsider sold out of its initial

print run of 5,000 copies in one day.

Cyril Connolly said it was “one of the most remarkable first books I

have read for a long time” while Philip Toynbee called it “a real

contribution to our understanding of our deepest predicament”. It shows

how artists and writers such as Van Gogh, Kafka and Hemingway are

affected by society and how they in turn, as “outsiders”, impact on

society. John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger had just opened at the Royal

Court and the term “Angry Young Men”, invented by JB Priestley, was

first used in the New Statesman the following week and stuck. Although

Wilson said it was not a group with which he identified, his later work

The Angry Years (2007), recalls the period and the characters of

Osborne, Kingsley Amis and others.

The Outsider made Wilson £20,000 (equivalent to £430,000 today)

in its first year. He said later that he had not been surprised by the

positive reaction but had not anticipated what followed – “the

tremendous backlash, and the attacks on me which I found pretty hard

going.” Referring to Religion and the Rebel (1957), his novel

Ritual in the Dark (1959) and other works over the coming decade, he

noted, “I’d produce some book which I knew to be brilliant and I’d get

lousy reviews.” Evidently, the literary Establishment was not pleased at

an uneducated, working class writer getting so much attention and

praise, despite their initial enthusiasm. With media attention now

focused on Wilson’s domestic affairs, his publisher suggested he leave

London for Cornwall, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Wilson’s book Strength to Dream (1962), a study of imagination in

literature, had a title he later said he should have used for his

autobiography, based on a phrase by George Bernard Shaw: “Every dream

can become a reality in the womb of time for those who have the strength

to dream.” Wilson was one who had that strength to dream and to see his

dreams become reality in print.

In his Introduction to the New Existentialism (1966), Wilson

revisited the themes of The Outsider, suggesting that the “old”

existentialism “was a philosophy of man without an organised religion...

Man stood alone.” He believed the challenge the “new existentialism” has

to face is this: “Can it again point to a clear, open road along which

thought can advance with the optimism of the early romantics?” He goes

on to demonstrate that it indeed can. Elsewhere he speaks of those

“curious moments of inner freedom” or (in his memoir Voyage to a

Beginning) “visionary intensity”, which hint at a purpose in an

otherwise meaningless world.

Towards the end of the 1960's an American publisher commissioned Wilson

to write a book on the occult. This took him in a new direction, towards

the realms of the esoteric and alternative history, at a time of

considerable interest in New Age subjects. The Occult: A History

(1971), revived Wilson’s critical reputation. “The reviews had a serious

and respectful tone that I hadn’t heard since The Outsider,” he

wrote. “With a kind of dazed incredulity, I realised that I’d finally

become an establishment figure.” He developed an interest in crime,

particularly the psychology of murder; his later works continued in the

dual veins of existentialism and mysticism, but all touching in some way

on what he called the “curious power of the mind that we hardly

understand”.

Wilson had suffered a stroke in June 2012 and was no longer able to

speak. He died in hospital with his wife Joy, and daughter Sally, at his

side.

Colin Henry Wilson, philosopher

and writer: born Leicester 26 June 1931; married firstly Betty Troop

(one son), secondly Joy Stewart (two sons, one daughter); died St

Austell, Cornwall 5 December 2013.

|