|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Amy Hale on Ithell Colquhoun, Celticity and Surrealism e-interview Rupert White

You're an American citizen who came to Cornwall in the 90's to study aspects of Celtic identity as part of a PhD with UCLA. How and why did you first become interested in Cornwall and Celticity? I was grabbed by the Celtic bug as an impressionable youth and even though my research has had many twists and turns, I feel as though Iím still exploring different facets of the same things I have always loved. I was interested in the whole Romantic Celtic thing as a teen, particularly loving the dreadful scholarship of the nineteenth century about ancient Arthurian solar cults and Druids. See, I really havenít changed much!

Cornwall was different. I was doing my PhD in the Folklore department at UCLA where I was then academically grounded in a very traditional Medievalist and linguistically based Celtic Studies concentration, which didnít really fit my interests in identity, politics, and economies. I already knew a bit about the cultural politics prior to my first visit to Cornwall in 1994. I spent that summer doing fieldwork to help shape ideas for my thesis and I was so passionately moved by the stories I heard and what I observed. I stayed with Cornish language speakers and cultural activists who taught me about Cornish history, the troubled economy and the inequities that Cornish people face. I felt then and I feel now that itís an important story to tell. As an American incomer I didnít have the Cornish/English cultural baggage and the dominant cultural narratives about Cornwall to shed, and as a result I think bring a different perspective to that dynamic. I relocated to Cornwall in 1995 and became very immersed in the culture and in Cornish cultural activism. Even though I am based in Atlanta now, Cornwall is still central to my work and has never ceased to interest and amaze me.

You were based in the Cornish Studies dept of Exeter University. It's striking that there is very little in the Cornish Studies literature on visual art and artists. In your Colquhoun book you describe it as 'an uncomfortable topic for scholars of Cornwall'. Can you explain this? The goal of Cornish Studies as a field, and one that I unequivocally support, is to re-center the Cornish people in their own story and to explore Cornish history, economics, and culture (and in the days of Charles Thomas, biology) from a Cornish perspective. Cornish Studies, like other area studies, aims to shed light on the historical contexts that have created the conditions of Cornish economic and cultural marginality. I still think this is a critically important project, and rather than having it forced into retreat into a corner of the University of Exeter, I think it needs to see more investment, and expansion because it is still vitally relevant. But I digress. You are right that the visual arts and the groups at Newlyn and St. Ives have not had much exploration within Cornish Studies. Part of that is because of the nature of those movements, and some because of the specialization of a somewhat small group of scholars which has traditionally been more focused on history and politics. The art movements in Newlyn and St. Ives generally lacked Cornish inclusion or influence, and in the case of the Newlyn School the Cornish portrayed as subjects in the paintings were very romanticized. Those art movements arose when much of the native Cornish economy had collapsed and we start to see the rise of tourism and what we might call creative economies start to take center stage as economic drivers in Cornwall. Itís a sore spot with Cornish Studies scholars (and others of course!), because while these might reasonably form part of an economic strategy, as a primary economic strategy we have seen where they donít translate into prosperity and stability for the majority of Cornish residents. I will say, though, that although the idea of creative economies has had some justifiable backlash and some excellent critique of late, there is a lot of fabulous and significant Cornish creativity in the arts out there that is very, very worthy of scholarly attention. The tremendous success of Mark Jenkinís Bait comes to mind.

Even though Colquhoun had an extremely romantic sensibility about her love of the Celts, she really did understand and acknowledge the political dimension and the colonialism at the core of it, and I think that does differentiate her somewhat. Yeats was a primary influence and the Irish writers who she loved certainly had a strong political commitment to their work that impacted her own interest in Celtic cultures. Colquhoun wasnít actively involved in what we call the Cornish movement, but she did get it, and I think she would have believed herself to be an ally. She believed that Cornish culture was distinct and that it was important to preserve it. Having said that, she was deeply anti-modernist and she probably would have preferred Celtic cultures to be preserved in aspic. She also firmly believed that there was a Celtic cultural substrata through all of Britain which certainly would have tempered any nascent activism.

To what extent was she able to engage with Cornish revivalists, activists and historians like eg James Whetter? She must have been disappointed she wasn't asked to become a bard of the Cornish Gorseth... Her engagement with Cornish activists and historians such as William Paynter and Hugh Miners was significant but not extensive, and mostly about areas that were of interest to her, such as Witchcraft. James Whetter was a fascinating character (for the uninitiated, Whetter was the founder of the Cornish Nationalist Party, which was a different party now considered slightly to the Right of Mebyon Kernow), and at one point he was interested in having her write for his magazine, An Baner Kernewek, but I donít believe the relationship progressed much. I think her intersections with Whetter came about because he was engaged with Colin Murrayís Celtic flavored spiritual group the Golden Section Order, to the extent that he was publishing ads in the back of their newsletters and seeking support from Murrayís constituency. He was clearly trying to inspire folks who had an interest in Celtic nativist spirituality, and he and Colquhoun might have found common ground there. While Colquhoun clearly knew about Cornish revivalist activities, there is no real evidence that she engaged in that milieu at all. I would think that being rebuffed by the Gorseth may have taken the wind out of her sails in that respect, but she was very actively involved in a type of Druidry that was seen by the Welsh and Cornish Gorseth as a cultural imposition, appropriating Celtic institutions for very different ends. There was an active conflict going on in the early 1960s between the English and Celtic Druidic/Bardic orders, and she was on the wrong side of it. Itís hard to know how this may have impacted any potential interest she may have had in the Cornish movement. I would say that a middle ground for her was her interest in Denys Val Bakerís Cornish Review, to which she contributed in 1971.

Thinking about your book more specifically, can you say something about the title? Where did this come from? "Genius of the Fern Loved Gully" is a line from that absolutely wonderful section in the opening of The Living Stones, where she offers thanks to the Spirit of Lamorna: "O rooted here without time, I bathe in you; genius of the fern loved gully, do not molest me; and may you remain forever unmolested." I think it beautifully expresses her animism and her deep love and respect of Lamorna. Of course when choosing the title of the book we liked the many layered meanings of the phrase.

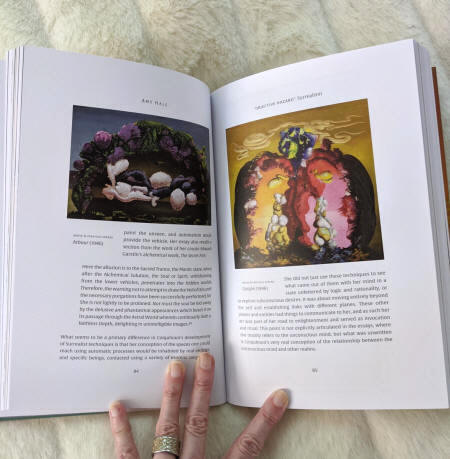

It's my opinion that when Colquhoun discovered automatism at the Surrealist retreat with Roberto Matta and Gorgon Onslow Ford in Chemilieu in 1939, that her relationship with Surrealism changed and blossomed. Through automatism Colquhoun was able to reconcile her own occult understanding of the world and its many dimensions. It shifted her expression of esoteric ideas from a symbolic approach to directly accessing other dimensions and entities through automatic processes. As a result, Colquhounís later Surrealism is much less representational and dreamlike than some of the other Surrealists. There are no magical images to decode the meaning of because the work itself is an act of magic. While there is no doubt that other Surrealists had their own esoteric practices, in Colquhounís case her work was very influenced by a range of Hermetic theories such as Kabballah and alchemy in which she was very deeply immersed. I donít believe that other Surrealists had the level of engagement with occult traditions and groups at the level that she did.

There are a few unanswered questions about Colquhoun herself. This would include her sexuality. In the book you mention an affair with a woman, and suggest that she was bisexual. Perhaps her interest in the androgyne, which can be traced back to her teenage years, is a reflection of this? I agree that this aspect of Colquhounís life is at this point rather mysterious. The challenge in looking at it as a scholar is that I want to be careful to respect how she might have viewed her own sexual orientation and gender identity and distinguish that with how we might talk about orientations and identities today. I am (pretty) certain that she would never identified herself as either bisexual or queer, yet her own history of same sex attraction and her the themes of her work encourage rich and interesting queer readings that I believe have a great deal of merit apart from what would have been her own identity. And I do believe that her interest in the androgyne was related to her same sex attraction and certainly her own understanding of an integrated self with respect to gender.

Another which, again, you acknowledge in the book relates to her failure to respond to Wicca and to Gerald Gardner's idea of witchcraft. She was aware of it but didn't seem interested in engaging with it. What do you make of this? Colquhoun was interested in Witchcraft in many forms. It shows up in her fiction and she had a research folder dedicated to press clippings and correspondence about witchcraft in the 1960s. She knew Gardner, visited him more than once and had interviewed him for a London magazine in 1954. She corresponded with Cecil Williamson for many years and knew of Traditional (non-Gardnerian) groups such as The Regency when they were in their earliest developmental stages. She was also interested in and made use of traditional healers and psychics. She even had correspondence with Margaret Murray! Although I canít be sure why Colquhoun never became involved in coven-based magic (as far as we know!) my guess is that her primary spiritual and magical focus, the one to which she was most drawn, was Hermetic initiatory traditions that she believed had a link with the Golden Dawn and with Perennial wisdom traditions. I think she believed in the idea of a ďwitch cultĒ, but I also suspect that she likely would not have personally resonated with the ecstatic ritual of Wicca.

My feeling is that Colquhoun was known for different things by different communities. For years art historians knew her as a Surrealist who was into the occult and who parted ways with the British Surrealists over it. Occultists knew her for Sword of Wisdom, likely The Living Stones; Cornwall and possibly Goose of Hermogenes. Some occultists may have remembered her other writings in Prediction, Ore or Wood and Water and knew little of her career as a Surrealist. In the last decade we have seen enormous popular and academic interest about the role of the occult and esoteric practice in the arts, and Colquhoun provides an amazing example of this synthesis. With the acquisition of her visual archives by the Tate we have an amazing opportunity to further explore how her beliefs and practices went hand in hand with her tremendous creative output. While I think that her own affiliation with Surrealism is very important, there may be more benefit in understanding her wider corpus of work within the framework of esoteric art, drawing comparisons with figures such as Hilma af Klint. There is no doubt that Colquhoun was ahead of her time in a number of respects. Iím not sure I will ever catch up with her, but I suspect I will have a lifetime of trying.

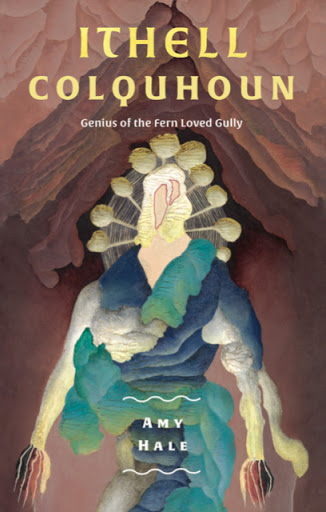

Genius of the Fern Loved Gully: The Supersensual Life of Ithell Colquhoun, Artist and Occultist by Amy Hale. Strange Attractor Press 2020. ISBN: 9781907222863 http://strangeattractor.co.uk/shoppe/ithell-colquhoun/ See 'features' for a review by Richard Shillitoe: http://www.artcornwall.org/features/Richard_Shillitoe/Amy_Hale_Genius_Of_The_Fern_Loved_Gully.htm https://independent.academia.edu/AmyHale 11.9.20 |

|

|

I

very quickly learned that the popular vision of the Celts as dreamy

Otherworld visionaries, while enticing, is not even remotely the story

of the Celtic peoples who have been so indelibly shaped by colonialism

and marginalization, but wow, how it continues to sell! My BA was in

Anthropology, and I went to an Honors College in Florida that required

significant original research for a BA thesis. It was really more like a

Masterís degree. I did ethnographic fieldwork in Ireland for several

months in 1989 looking at how Irish mythology and ideas about the Celts

was influencing Ireland as the EU was in a formative stage. Cutting my

teeth on Ireland was great since there is so much documentation about

the historical development of Irish Celtic identities and Irish

ethnonationalism, but I honestly never felt any particular connection

with Ireland, although I do love it because Ireland is pretty awesome.

I

very quickly learned that the popular vision of the Celts as dreamy

Otherworld visionaries, while enticing, is not even remotely the story

of the Celtic peoples who have been so indelibly shaped by colonialism

and marginalization, but wow, how it continues to sell! My BA was in

Anthropology, and I went to an Honors College in Florida that required

significant original research for a BA thesis. It was really more like a

Masterís degree. I did ethnographic fieldwork in Ireland for several

months in 1989 looking at how Irish mythology and ideas about the Celts

was influencing Ireland as the EU was in a formative stage. Cutting my

teeth on Ireland was great since there is so much documentation about

the historical development of Irish Celtic identities and Irish

ethnonationalism, but I honestly never felt any particular connection

with Ireland, although I do love it because Ireland is pretty awesome.

_small.jpg)